Growth Models: The Need for, and Types of, Aggregate Demand

In Political Economy, growth is conventionally understood to be a function how workers are trained, how structured labor markets operate, and how firms finance themselves. Economic gains, from this vantage point, are largely a function of "supply-side" institutions. The policies that make firms more competitive or workers take on more specific skills matter most.

Countries can then be broken up into two main types: one withs the “liberal” institutions that foster innovation and flexible markets (like the U.S.) or “coordinated” systems that support incremental upgrades in manufacturing (like Germany). That's the TLDR version of a hugely influential body of work that goes under the Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) banner.

But when the financial crisis hit, and recovery remained elsuive, the foundations of that framework began to crack. Why did countries with similar institutional structures perform so differently? And why did so many advanced economies, despite stable institutions, enter a long-run funk of low growth and rising inequality that was catchily titled "secular stagnation"?

The “Growth Models” perspective has recently emerged to answer those questions. Drawing on post-Keynesian macroeconomics, this framework asks a different set of questions: firms matter, but who are they selling to? Institutions can lock in competitiveness, but how do they distribute wages, profits, and thereby purchasing power?

Basics of the Approach

The growth models perspective begins from a provocative, near century-old claim: modern capitalism is not driven primarily by supply-side efficiency or firm competitiveness, but by the search for demand. Without sufficient spending — by households, firms, governments, or foreign buyers - economic growth falters. And when growth slows, so too does political stability.

There are two fundamental questions that drive the analysis: who is buying what? and with what money? The composition and source of demand - be it from wages, credit, investment, or exports — shapes how economies grow, and for how long. The first scholars to really start asking these questions were Lucio Baccaro and Jonas Pontusson. Once they got working on the macro side, driven by some work on macro regimes, Baccaro, Blyth, and Pontusson pulled together a monster volume of contributions spelling out what studying capitalism from the demand side, particularly in a world of global but disintegrating trade yet ever free flowing capital, should look like.

At the heart of this approach lies a post-Keynesian and Kaleckian inspired understanding of the macroeconomy. That means a few key assumptions. First, it starts from the premise that capital and labor are locked in a continual struggle over the gains from productivity. Economic output increases over time, but who benefits and how those gains are distributed matters enormously.

This is not a mere technical detail: when a greater share of income goes to labor (rather than profits), there is more consumption in an economy, because workers have a higher “marginal propensity to consume.” By definition, poorer people are more likely to spend any additional dollar they receive to buy stuff rather than stash it in the stock market. That means they spend(/consume) more of what they earn.

Together, these mechanisms produce a feedback loop:

rising wages → higher demand → greater investment → rising productivity.

That was the logic of the postwar wage-led growth that is often regarded as the golden age of capitalism despite capital mostly locked inside national borders. This logic remains the theoretical foundation for the growth models approach. But we've been in an age of wage stagnation for basically 50 years, so countries needed to find new ways to grow.

From this vantage point, income distribution is not just a moral or political issue. It’s an economic one. If too much income flows to the top, i.e., those who are less likely to spend it, demand falters. If productivity gains aren't distributed back into domestic wages (and instead remain with capital), economies must look elsewhere to sustain growth: through household debt, public transfers, or foreign buyers. But each of these substitutes brings its own fragilities.

The broader implication is that growth is not self-sustaining. There is no “natural” equilibrium to which economies revert. Instead, capitalism is an unstable system, constantly searching for new sources of demand, new political settlements, and new methods of accumulation.

That's why, for growth model analysts, aggregate demand matters more than institutional typologies or firm-level competitiveness. Countries grow not just because they become more efficient. They are ready to become more efficient because someone - somewhere - is spending. That demand can be internal (wage-led, investment-driven, state-backed) or external (export-led), but either way, its composition, sustainability, and political underpinnings are what matter most.

This helps explain a puzzle that other frameworks struggle with: why countries with similar institutions can experience very different growth trajectories, or why growth slows even when inflation is low, interest rates are near zero, and firms are profitable. These are not anomalies. They are symptoms of a broader stagnationist tendency in advanced capitalism: one where existing sources of demand have weakened and no new engine has fully replaced them.

This also leads to a second, critical insight. Countries are not islands and neither are their growth models. Their growth models are shaped and constrained—by their place in the global economy. Credit-financed consumption requires global capital inflows. Export-led models depend on trading partners with the willingness (and capacity) to consume.

In this sense, growth models are both domestic and international. They emerge from national political bargains—between labor and capital, or governments and firms—but they are only viable within broader global configurations of demand, capital, and exchange.

What is a growth model?

Ok now that we've got all that throat clearing out of the way, what exactly is a growth model? As Baccaro, Blyth and Pontusson (2022) put it, it's not a policy agenda or a temporary strategy. It's a stable set of macroeconomic patterns: a way that a country generates, channels, and sustains demand over time.

Some countries rely on wage growth and household consumption. Others suppress domestic demand and lean on exports. Some combine public investment with private borrowing. But in each case, the model must be politically maintained—through coalitions, institutions, and ideologies that legitimize its distributional outcomes.

Models vs. Policy

It’s also important to distinguish between growth models from growth strategies. A strategy is what governments do. The policy roadmap to jumpstart or sustain growth, whether through tax cuts, infrastructure investment, or industrial subsidies. In contrast, a growth model is how an economy actually functions: how it generates demand, distributes income, and channels investment over time. It’s the underlying structure, not just the chosen tactics.

While strategies can be deliberate and short-term, growth models are deeper, slower-moving, and often path-dependent. The policy toolkit could be working to channel the growth model or to even undermine it, like when say a country that relies on consumption to grow redistributes wealth to the top through a tax cut...

Consumption-/Debt-Led Growth

I read Capitalizing on Crisis by Greta Krippner back in my undergrad years just as it was coming out, as the the aftermath of the global financial crisis was in full force. She examines how the American state managed to survive repeated legitimacy crises in the '60s and '70s as the costs of promising the American dream interacted with the hegemon's need to keep spending on defense, on the Vietnam War, on the Cold War.

Her answer was simple but fascinating to me at least - any time the US was facing growing societal backlash, it came up with a simple fix: let the people eat credit.

Krippner's logic becomes the premise for the first archetype of the GM approach:

When your economy relies on consumers buying stuff locally, and their wages aren't going, lend them the money to keep up their purchasing power and you can keep the economy kicking along.

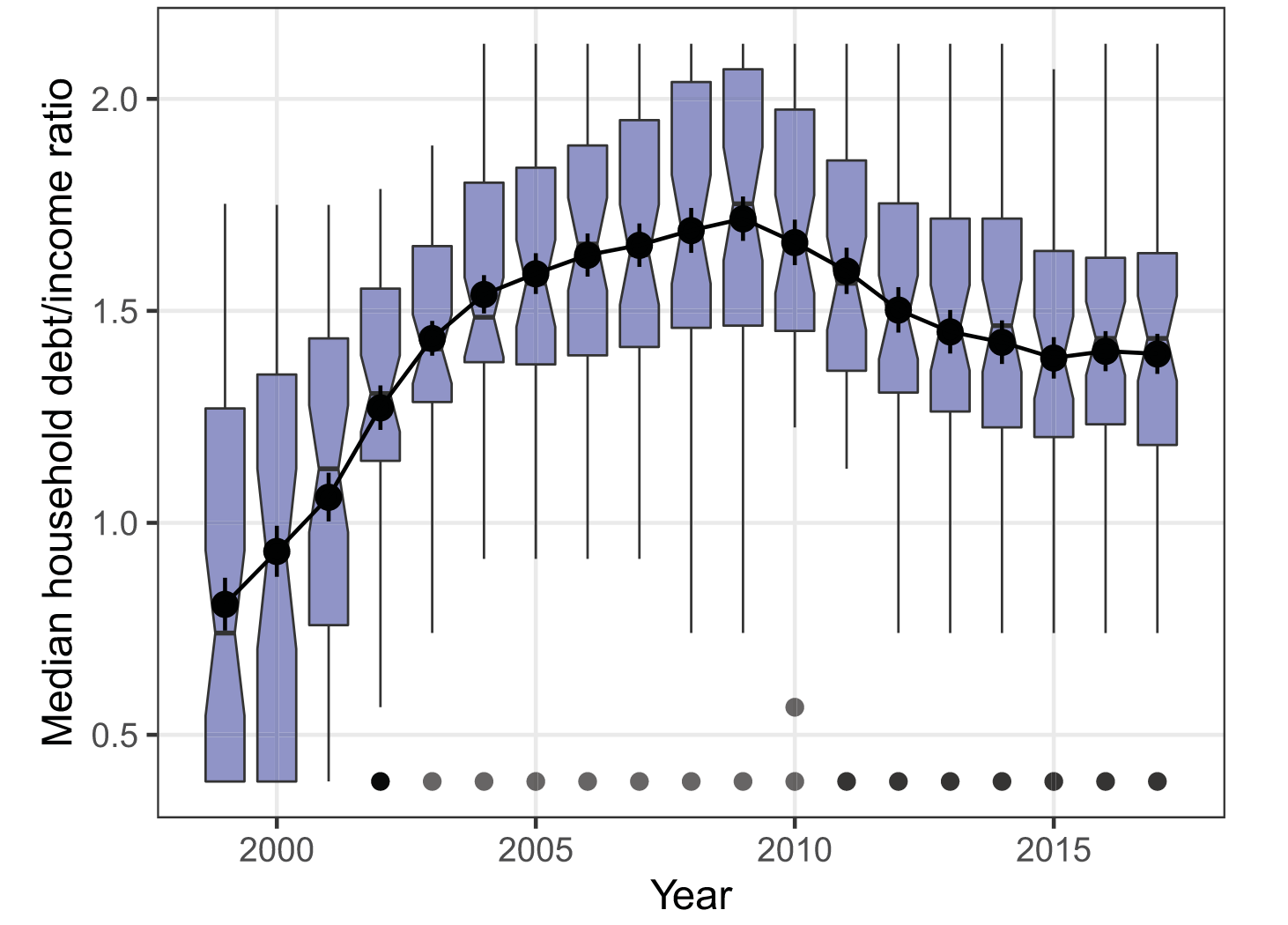

So in these systems, consumption isn’t primarily wage-driven. It’s debt-driven. While this was spelled out by a few different scholars initially, the most comprehensive description of the model comes from Alex Reisinbichler and Wiedemann. They point to two channels that have particularly helped substitute borrowing for wage growth: housing and personal debt.

1. The Housing Channel

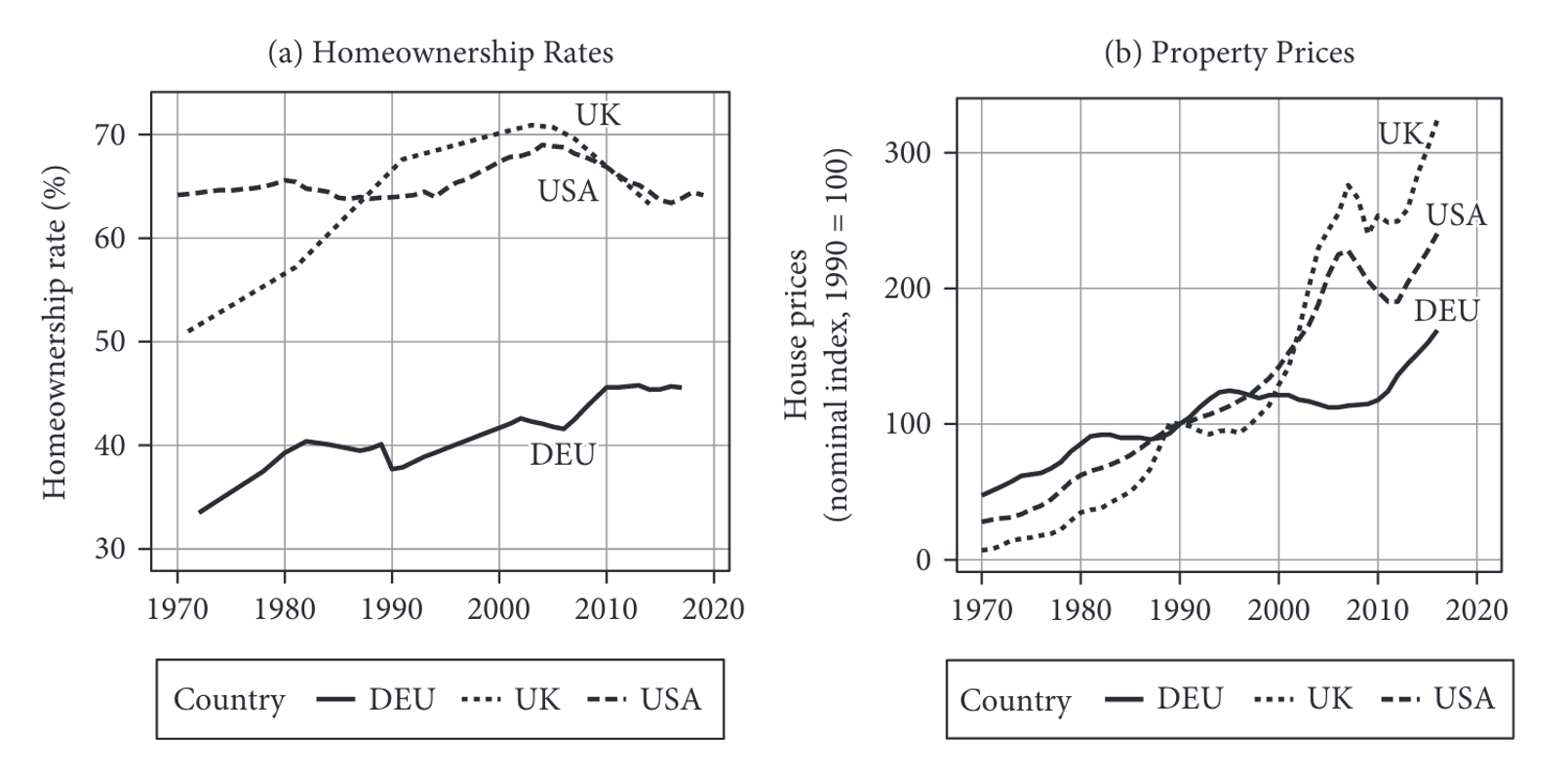

The first, the housing channel, turns rising home prices into a broader macroeconomic stimulus. When property values go up, homeowners feel wealthier and spend more. What economists call a wealth effect. More importantly, rising home equity can be used as collateral to take out loans: refinancing mortgages, borrowing against home equity, and expanding consumer credit.

You take on leverage to buy your house - via a mortgage - but then the house lets you lever up even more.

This mechanism is especially powerful in asset-based welfare systems, where social spending is limited and wealth accumulation (usually via housing) plays an outsized role in ensuring security. In such regimes, housing markets become central to macroeconomic management. Rising home values are not just good news for individuals. They’re the engine of the national growth model.

2. The Income Maintenance Channel

But not everyone owns a home. So how do those without assets keep up? Households need to borrow to "smooth income" losses when wages stagnate, jobs are lost, or living costs rise. This effect is again dramatic in countries with weak welfare states.

When the safety net frays, credit markets fill the gap. Credit becomes a private substitute for public policy. Recent research shows that households borrow more when they live in places with stingier unemployment benefits. In the US, a 10-percentage-point drop in unemployment benefit generosity, for example, is associated with a 30% rise in household debt — about $5,300 on average.

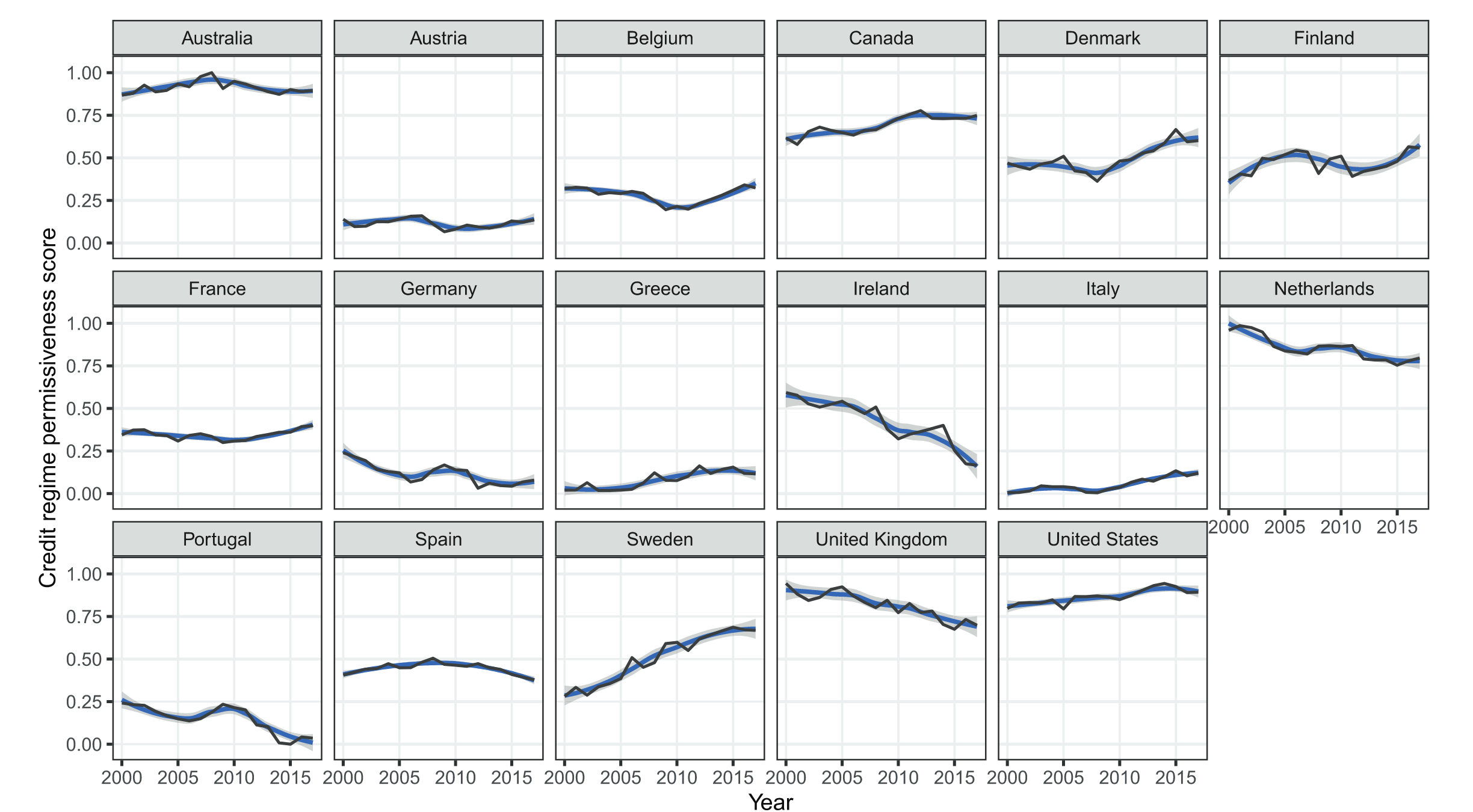

These credit channels are not just economic mechanisms. They’re inherently political. The FIRE sector (finance, insurance, and real estate) directly profits from growing debt and expanding asset values. But so do millions of homeowners who benefit from rising prices, tax breaks, and permissive lending rules. As a result, both center-left and center-right parties have converged around pro-credit policies, especially during economic downturns.

To put it simply, borrowing replaces bargaining. When wages no longer rise through collective power or government support, households are nudged to go it alone with a (usually maxed out) credit card in hand.

Asset Inflation as Growth Policy

This growth model generates a highly unequal political economy. Existing asset owners win big, as their wealth increases and their ability to borrow expands. Those without assets must take on more debt just to maintain living standards. And as housing prices rise faster than wages, the ability to borrow becomes increasingly unequal.

Yet the consumption model can’t go on forever. Its core mechanism — asset inflation — is inherently unstable. Asset bubbles eventually burst, and debt burdens become unsustainable.

But not every crash happens the same way, at the same speed, or with the same effects. Your place in the financial hierarchy - how much other people want to hold your currency - conditions the sustainability. Some economies (like the US) can weather crashes by attracting foreign capital or running large deficits. Others, like Southern Europe or Turkey, have faced far more brutal corrections.

And the rising borrowing does appear to fuel the far right.

Still, many countries have tried their hand at consumption-led growth, from pre-2008 Spain and Ireland to Brazil and beyond. What distinguishes success or failure is not simply access to credit, but whether that access is politically and economically sustainable — and whether the growth it enables can survive rising debt, falling wages, or shifting global conditions.

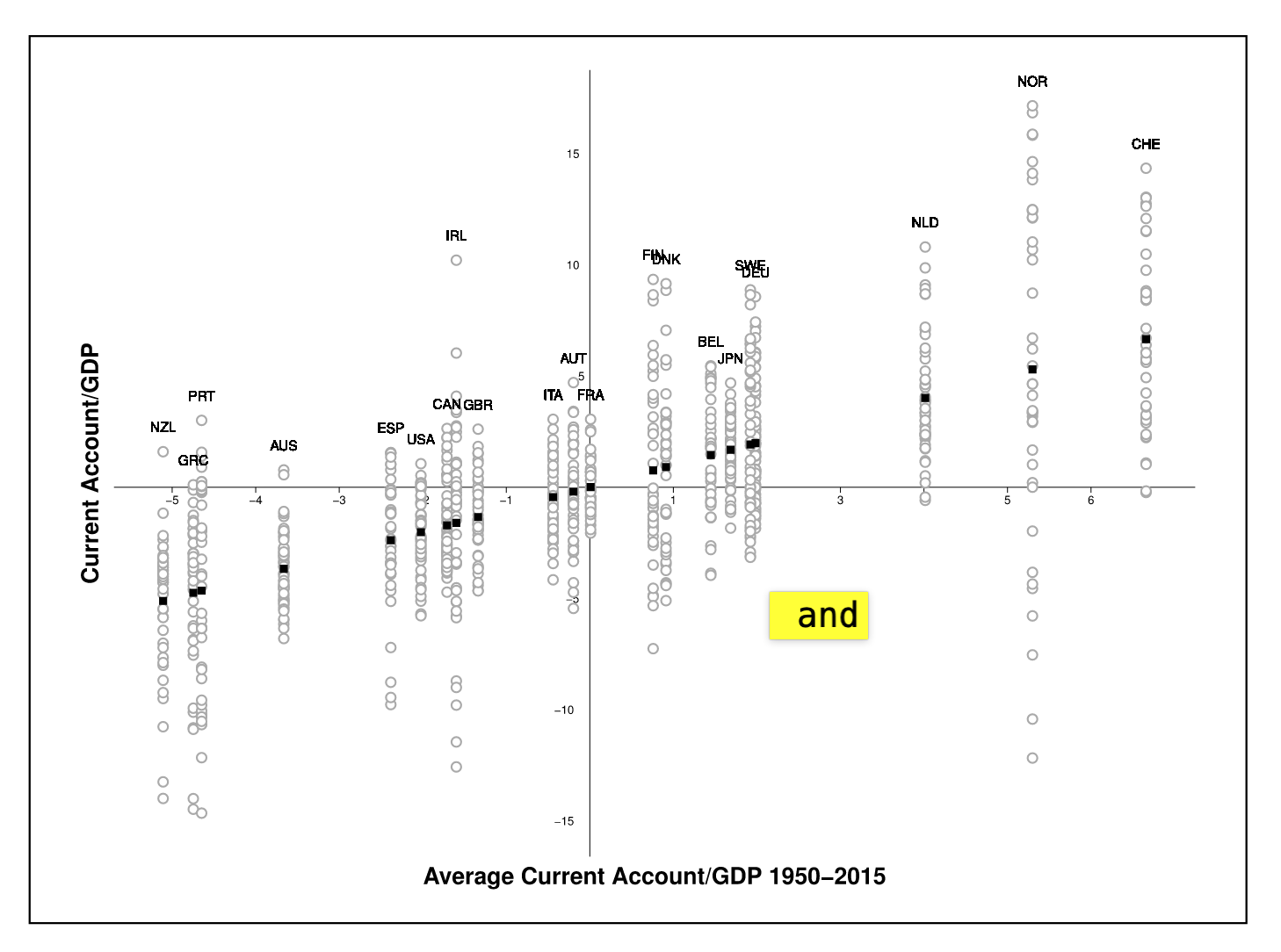

While debt-fueled consumption has driven growth in the Anglo-American world, an entirely different path has underpinned the economic success of countries like Germany, South Korea, and Japan: export-led growth. These models don’t rely on household borrowing to sustain demand. Instead, they suppress domestic consumption in order to boost price competitiveness abroad. The engine of growth is the rest of the world and the fuel is relentless export surpluses.

At the heart of this strategy is a remarkably consistent set of policies: coordinated wage bargaining to keep labor costs low, conservative fiscal and monetary policy, strict housing credit regulation, and a relatively underdeveloped financial system that channels excess savings abroad. As Baccaro and Höpner (2022) note, these ingredients together create a powerful force of real undervaluation: a situation in which domestic prices rise more slowly than those of trading partners, making exports systematically cheaper.

This is not simply the result of market forces. It’s a set of political choices. German policymakers, for example, have long sought inflexible exchange rate regimes that translate domestic wage restraint into improved international competitiveness. From the gold standard to the euro, the goal has been to “lock in” relative prices and prevent currency appreciation that could undercut exporters.

These surpluses are not just short-term phenomena as standard economic theory would expect. They reflect long-term institutional and political differences with labor markets playing a critical role. Manger and Sattler (2020) show that countries with highly coordinated wage bargaining systems (put simply, places with high union density) are far more likely to run surpluses than those with fragmented or individualized wage setting. In coordinated systems, export sectors enjoy stable, moderate wage growth, preserving price competitiveness and bolstering their political influence.

Focusing on OECD countries, they estimate that countries with the least coordinated systems consistently run current account deficits of about 2.5% of GDP, while the most coordinated systems generate surpluses around 3.4%.) And crucially, these patterns hold regardless of the exchange rate regime—coordinated wage moderation alone can produce structural surpluses.

That is not to say exchange rates don't matter. In the case of the eurozone, Johnston and Matthijs (2022) argue that during the euro’s first decade, growth model diversity was tolerated. But after the debt crisis, the institutional reforms imposed by creditor countries (basically Germany) enshrined export-led strategies as the only acceptable path to growthtab:https://academic.oup.com/book/44862/chapter-abstract/384807155?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false). Fiscal rules were tightened, domestic demand was deprioritized, and structural reforms in the periphery were aimed at replicating German-style competitiveness.

The euro crisis was not just a monetary breakdown. It was a moment of the German's enforcing what they think of as the optimal growth model. Their growth model. But if everyone is trying to export, who is going to buy anything?

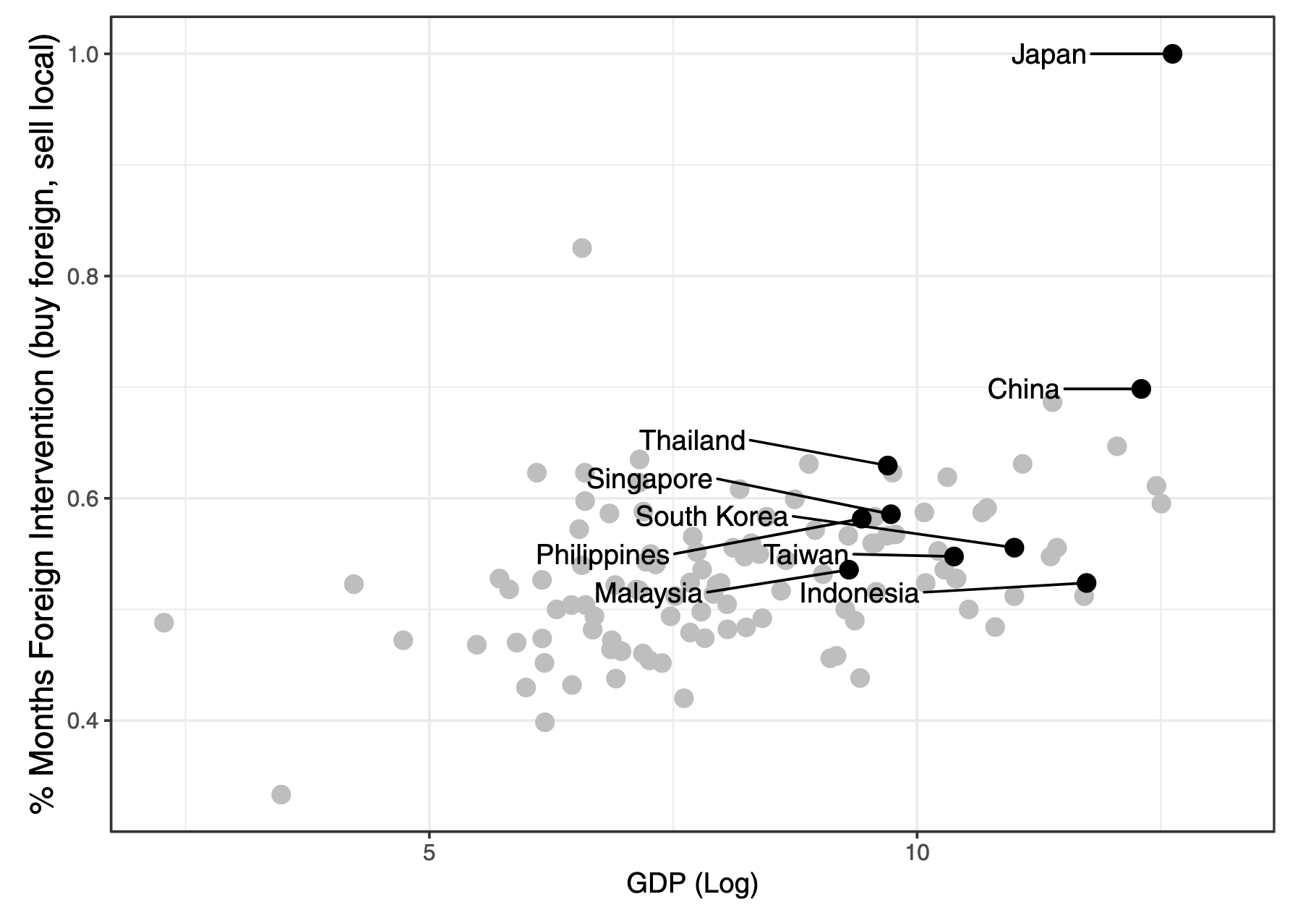

I am only loosely trying to pick on Germany. In East Asia, countries like Japan and South Korea have relied heavily on undervalued currencies to support export competitiveness. But rather than wage restraint, the key lever is often active intervention in the foreign exchange market. Manger and Nones (2025) use a novel method to track this: they apply machine learning to decades of financial newspaper articles in Japan and Korea to measure when exporters lobby for a weaker currency. The results show a strong link between these signals and subsequent government interventions to depreciate the exchange rate.

In both Europe and Asia, the export-led model relies on holding down domestic demand whether through wage restraint, tight housing credit, or limits on fiscal expansion. Investment flows abroad, domestic consumption is muted, and the health of the economy depends on demand elsewhere.

But this model is increasingly strained. As protectionism rises and geopolitical frictions mount, relying on foreign markets is no longer a safe bet. Eurozone surplus countries face pressure from the U.S. and developing economies alike. And in Asia, the politics of currency intervention grow more contested as citizens push back against stagnant wages and declining purchasing power.

The export-led model is powerful, but it comes with tradeoffs: stagnant domestic wages, low consumption, and dependence on external conditions. It’s a formula that worked in the golden age of globalization, but it may be far harder to sustain in the age of fragmentation.