How Supply-Chains changed Domestic Lobbying

Over the past two decades, globalization hasn’t just moved factories overseas. It rewired the circuitry of corporate influence. Firms aren’t just big anymore. They’re embedded: in production networks, in local labor markets, in cross-border policy fights. And this embeddedness is changing how they lobby, where they lobby, and who they lobby with.

Recent research reveals three major shifts. First, firms that sit at the center of supply chains — not necessarily the largest companies, but the ones that have the most economic connections — are increasingly the ones shaping policy. Second, multinational corporations have quietly become powerful foreign influencers by leveraging domestic affiliates and adapting to local lobbying rules. And third, once those firms put down roots, they don’t just lobby alone. They forge new coalitions, transforming the politics of trade and regulation in the countries where they invest.

What follows is a review of some of the most compelling new evidence on this transformation.

Centrality is just as Important as Size

The classic account of special interest politics puts "narrow" interests in the driver's seat. The idea is intuitive: firms with concentrated exposure to costly policies, like carbon pricing, face higher stakes and fewer coordination problems than the broader public. When climate policy comes up, we suspect it’s the usual suspects showing up to water down a bill: oil majors, coal producers, big emitters—who organize, spend, and obstruct.

But that story is incomplete. New research shows it's not just size or direct exposure that matters, but how central a firm is to the economy. A firm’s centrality within production networks - its role in supply chains, the reach of its supplier and customer ties, and the geographic spread of its operations — can be just as important in shaping political behavior. It’s not just the firms with the biggest emissions that spend and win legislative fights; it’s the firms with the widest webs that garner support.

This becomes particularly clear in a landmark study by Cory, Lerner, and Osgood (2023), who argue that carbon pricing doesn’t just threaten firms that emit carbon. It also hits those that rely on carbon-intensive inputs or sell to carbon-reliant customers. A fertilizer company, for instance, may not be a top polluter itself, but if it uses phosphate rock sourced through carbon-heavy mining, it faces indirect costs. The same goes for concrete pipe manufacturers who rely on emissions-intensive cement, or freight companies whose biggest clients operate in fossil-fueled sectors.

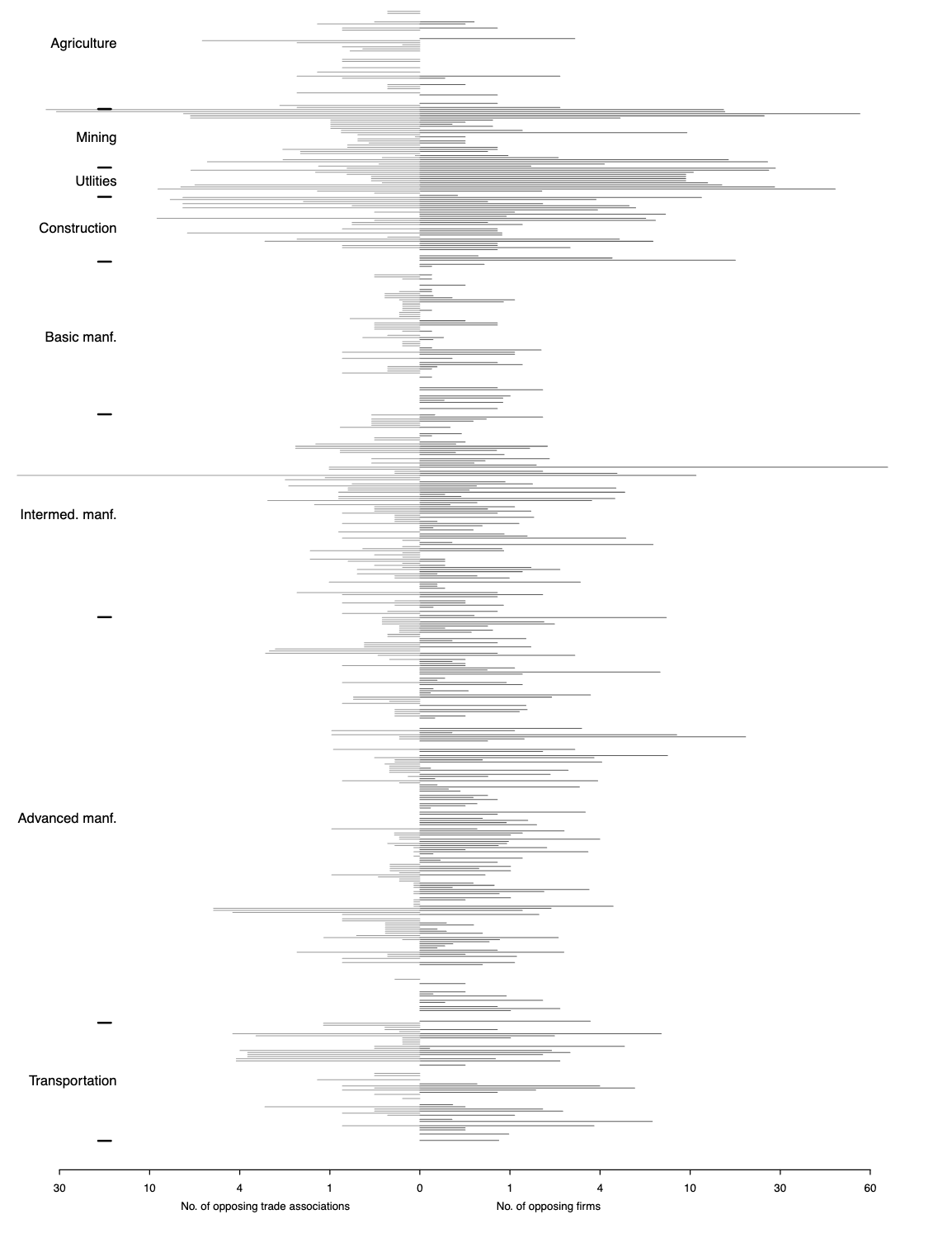

The authors bring together several data sources to make this argument empirical. They begin with estimates of CO₂ intensity across U.S. industries and then trace how these intensities flow across the supply chain using input-output tables.

This allows them to construct weighted measures of upstream (inputs) and downstream (outputs) carbon exposure, in addition to firms’ direct emissions. These three variables—direct, input, and downstream CO₂ intensity are then matched to firm-level lobbying behavior and coalition membership on climate issues.

The results are astounding:

We find that 73% of firms and 58% of associations that opposed climate action have no business activity in these industries. To put this in context, that top 20% of industries account for 67% of all US emissions.20 Looking within the goods+ industries only, we find that 58% of firms and 42% of associations have no business in the top-20% most emitting industries. Among this subset of industries, the top-20% most carbon-intensive industries account for 79% of emissions.

The indirect exposure, the supply-chain, is doing the real political work.

If Cory et al. show how economic ties transmit policy costs, Betz and Hummel (2025) show how they transmit political power. In their study of U.S. anti-dumping petitions - formal requests by domestic firms for government protection against foreign competitors selling goods below market value - they argue that firms embedded in dense domestic production networks are more likely to receive favorable policy treatment. That's not necessarily because of their own heft, but because their petitions can be framed as protecting broader economic ecosystems.

Their empirical setup is clever. Anti-dumping cases are a rare window where firms must publicly request protection giving researchers the ability to view both the intention and the outcome. Betz and Hummel combine these petitions with newly constructed data on supplier–customer networks to measure how many upstream firms stand to benefit indirectly from a successful case. The more economically central the petitioning firm, the more likely its petition is granted.

Lawmakers pick up on this too. Analyzing briefs submitted by Members of Congress to the U.S. International Trade Commission, they find frequent appeals to the indirect benefits of trade protection. That politicians call out the benefits that re not just to the firm filing the petition, but to its suppliers and related industries.

This logic of embeddedness as political capital also explains a more dynamic strategy: reshaping your geographic footprint to build allies. In a study of U.S. subsidiary investments from 1997 to 2018, Bisbee and You (2024) show [that firms disproportionately open new subsidiaries in electorally competitive districts, where local job creation can translate into real political returns](tab: https://hyeyoungyou.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/subsidiaries.pdf).

Firms are meant to fear investing in places where the policy future is unclear, but some see it as an opportunity to extend local investments for national returns.

Their argument is straightforward: jobs are politically valuable, especially for vulnerable incumbents. Firms, especially those in geographically flexible sectors, can use that to their advantage. A small subsidiary in a swing district becomes more than just an operational choice. It becomes a form of lobbying by other means.

The authors track all subsidiary openings by the top 500 U.S. parent firms over two decades, linking them to congressional districts, election results, and local economic conditions. [The patterns are robust: as electoral competition increases, so does the likelihood that a firm will invest locally.] These investments are then referenced in campaign materials, speeches, and constituent communications—further cementing the political bond. While conventional factors, like a county's potential job pool, tax rate, etc. matter more, firms do appear to opportunistically open affiliates on the margins.

You don't have be a giant or a Big Tech player to win in DC. Firms that anchor supply chains, touch multiple sectors, and create local jobs in strategic places are better positioned to lobby, to win favorable policy, and to fend off regulation.

Supply-chains turn MNCs into Foreign Influencers

In much of the policy debate, we assume the most active political players in Washington are domestic giants—companies like ExxonMobil, Walmart, or Ford. And that’s not wrong. But it misses something important. The nature of globalization, and of supply chains in particular, has blurred the lines between domestic and foreign actors. Multinational firms don’t just produce across borders—they now lobby across them.

Three new studies by Jieun Lee trace this transformation, and in doing so, they reveal how foreign-headquartered multinationals have quietly become major political players in the U.S., often outspending and outmaneuvering their domestic peers.

Most foreign firms doing business in the U.S. are expected to disclose and limit their lobbying under FARA (the Foreign Agents Registration Act), a law designed to mitigate foreign influence. This of course skyrocketed to fame during the Manafort affair, which subsequently lead to a massive spike in MNCs reporting their lobbying antics.

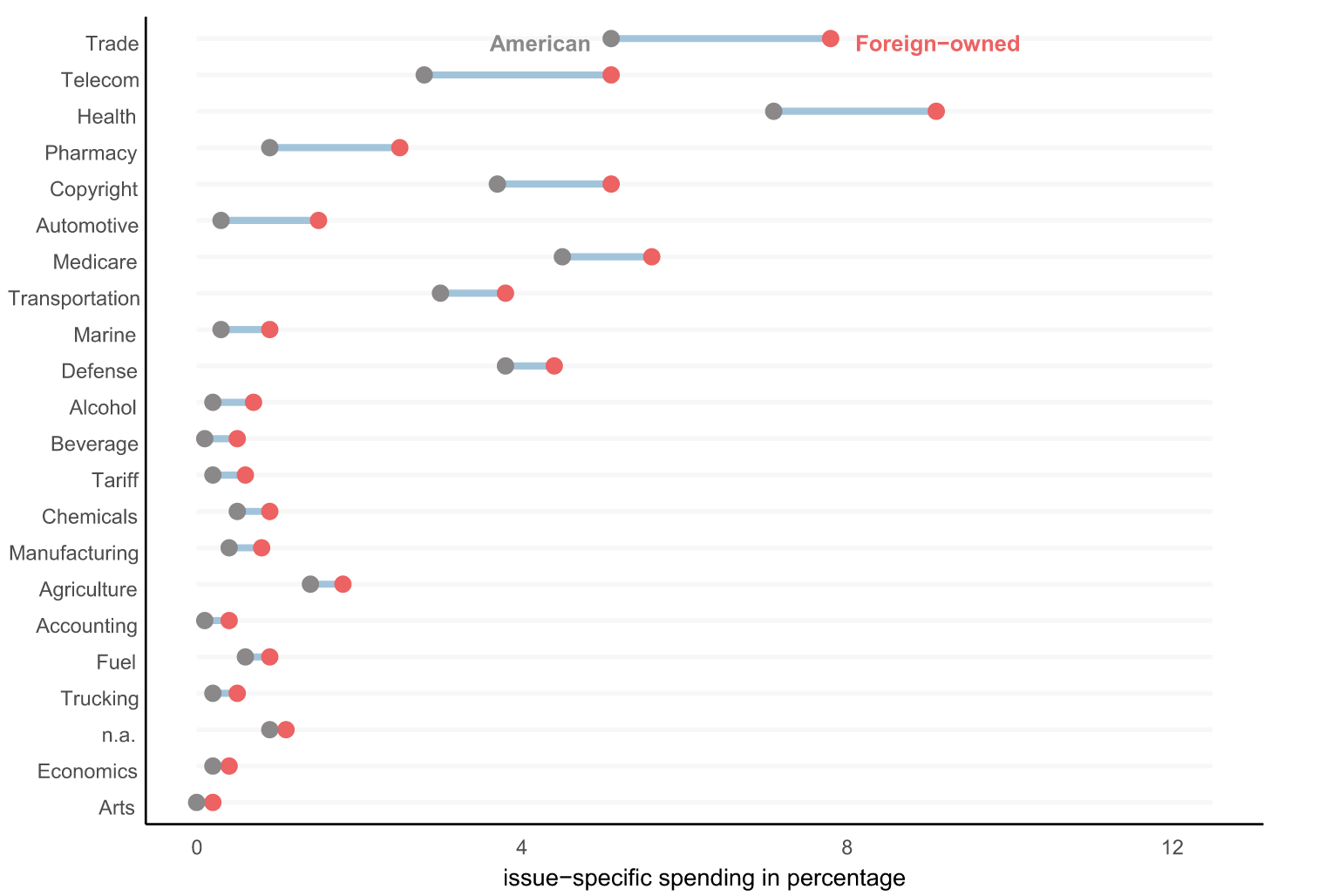

But Lee (2024) shows that firms can sidestep FARA by lobbying through their U.S. subsidiaries under the domestic-facing LDA (Lobbying Disclosure Act). In 2016 alone, foreign-owned firms spent over $395 million lobbying under the LDA. That's more than all foreign lobbying under FARA combined.

These aren’t minor players. Using data from LobbyView matched with global ownership records, Lee (2024) identifies over 420 majority-foreign-owned firms reporting under the LDA. Crucially, these are not just legally domestic. They’re strategically active. They lobby more intensely, on more issues, and with greater precision than their American counterparts. The figure below charts the stark differences in foreign-corporate spending on issues compared to their domestic counterparts:

Take trade. It’s the most obvious arena where foreign firms have skin in the game. U.S. subsidiaries of foreign MNCs spent 8% of their lobbying budgets on trade policy, compared to just 5% for American firms. Pernod Ricard USA, a subsidiary of the French liquor giant, lobbied aggressively on trade liberalization with Cuba. And that pattern repeats across sectors—telecom, pharma, autos where foreign investment is deep.

What’s striking is that foreign ownership increases both the likelihood and the size of lobbying efforts, even after controlling for U.S. firm size, industry, and location. Foreign MNCs are not simply passive investors; they are active participants in shaping host-country policy. And the U.S. market’s size and institutional permeability make it an especially attractive target.

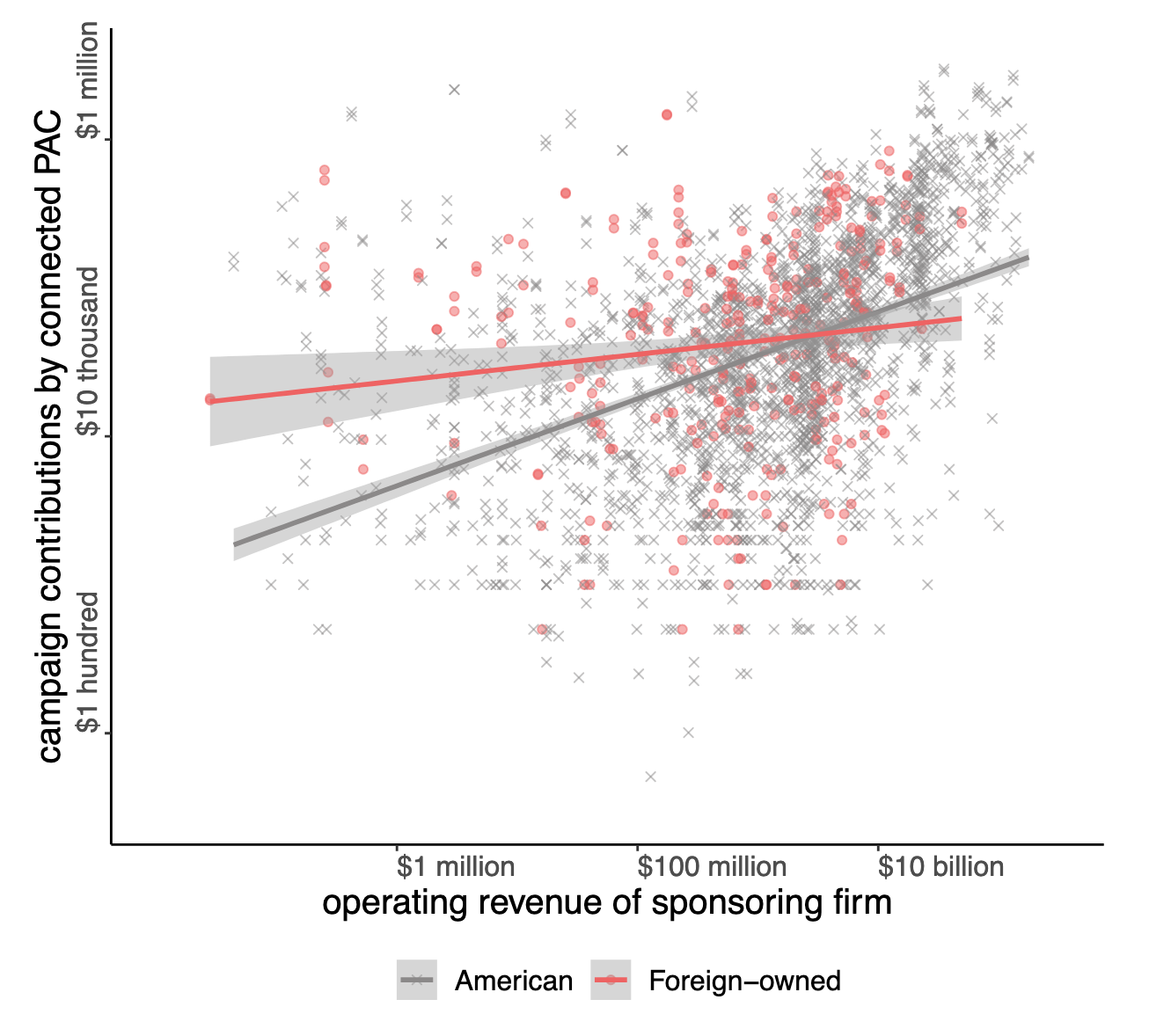

In a complementary study, Lee (2023) zooms in on Political Action Committees (PACs) that firms use to contribute to federal candidates. Despite bans on foreign participation in U.S. elections, subsidiaries of foreign MNCs can legally operate PACs so long as they’re domestically incorporated. And they do: foreign-connected PACs made up more than 11% of all corporate PAC giving in 2016.

These PACs don’t just mirror their American peers. They often outperform them. UBS Americas, a U.S. subsidiary of the Swiss bank, gave more in campaign contributions than Citigroup or Bank of America. Foreign-connected PACs also tend to give more evenly across parties and chambers, likely to hedge against political risk.

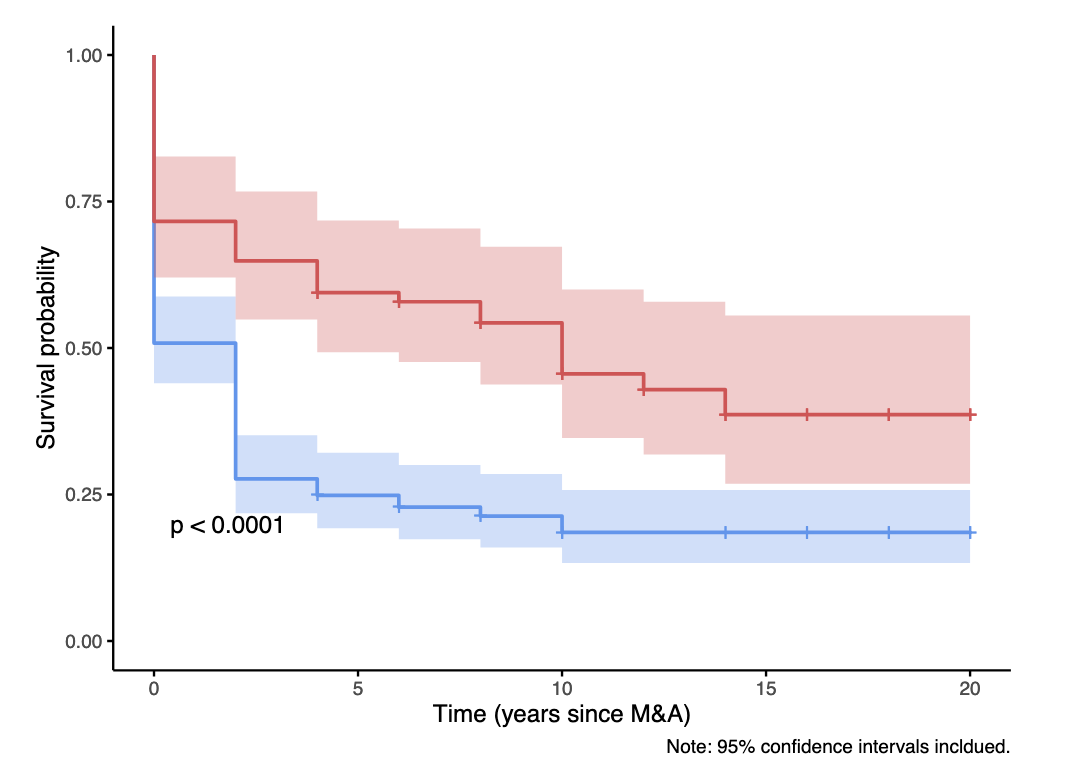

To explain how foreign MNCs build influence so quickly, Lee (2025) turns to mergers and acquisitions. When a politically active U.S. firm is acquired by a foreign parent, that firm’s existing PAC and lobbying operations are usually maintained. In many cases, they intensify. Foreign acquirers are far more likely than domestic ones to preserve their new subsidiaries’ political infrastructure.

The implications are powerful. A cross-border acquisition doesn’t just transfer ownership. It can transfer political capital. The new foreign parent inherits an embedded PAC, a network of lobbyists, and often a slate of congressional relationships. What’s more, the issues lobbied post-M&A shift: trade, IP, and cross-border regulation become more salient. It’s not just lobbying intensity that changes. It’s the agenda itself.

Put differently, foreign MNCs aren’t just playing the U.S. game. They’re using U.S. firms as entry points to project their own preferences into the American political system. And because they operate through legally domestic entities, their influence flies under the radar.

This makes intuitive sense. For many multinationals, the U.S. is the most important regulatory arena in the world. If you can shape American rules, you shape global outcomes. So when German automakers, Japanese pharmaceutical giants, or South Korean electronics firms acquire U.S. companies, they’re not just buying factories or brands. They’re investing in "voice."

And increasingly, they’re doing so at scale.

How MNCs adapt to local context

The growing role of multinational corporations in domestic lobbying might suggest a form of foreign encroachment. MNCs parachuting into Washington with external agendas and novel strategies. But the reality is that success relies on learning the rules of the game. They learn to lobby not just in the American market, but in the American way.

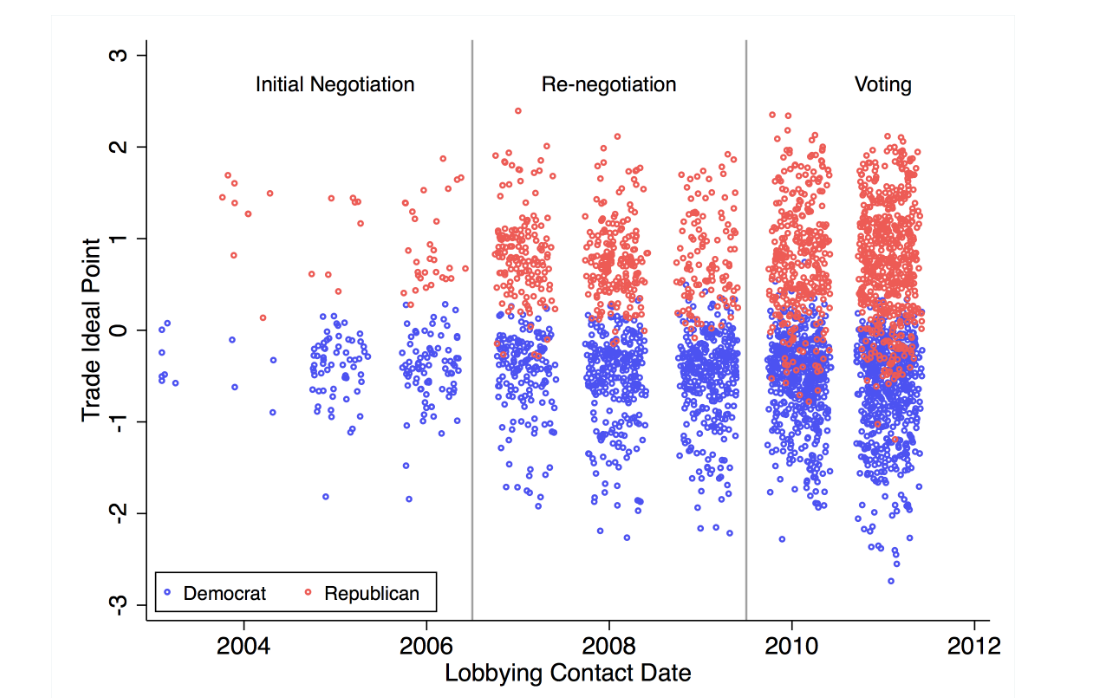

This transformation becomes particularly vivid in a study by You (2023), who traces the lobbying strategy of the South Korean government around the U.S.–Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA). Using the granular detail available in filings under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), which unlike the LDA requires foreign principals to disclose the exact timing, targets, and content of lobbying contacts, You reconstructs how Korea’s lobbying campaign unfolded over nearly a decade.

What stands out is not foreignness but familiarity. Lobbyists hired by the Korean government behave like seasoned Washington insiders because they usually are. The government concentrated activity not at the final vote but earlier—during the agenda-setting and renegotiation stages—when the agreement is still being shaped by bureaucrats and informal political pressure.

Unsurprisingly, they prioritize contacts with key committee members and swing legislators, and even align their lobbyist hires ideologically with their targets—ensuring that messages are delivered by trusted messengers. In doing so, they mirror core strategies theorized in the literature on informational lobbying and coalition-building.

You finds that weak and even strong opponents of free trade agreements were targeted more intensely during early stages — not to secure guaranteed votes, but to shape the terms of the agreement or forestall veto threats later on. Using ideological scores of both members and lobbyists, the study also shows that lobbyists were matched to members with aligned preferences, especially among those predisposed to oppose the deal. The strategy here wasn’t brute pressure. It was credibility through alignment, persuasion through familiarity.

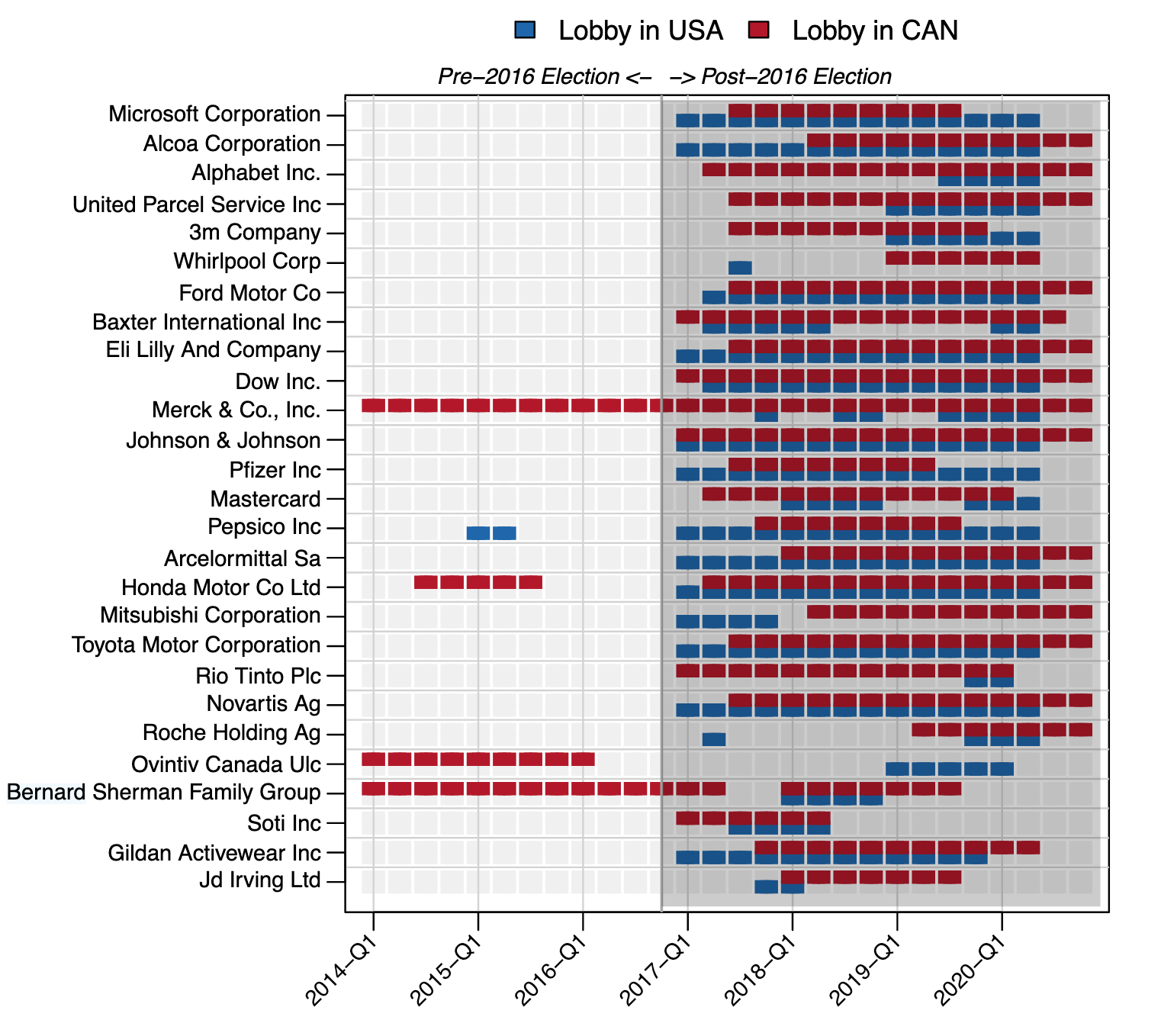

Institutional assimilation isn’t limited to isolated examples. Lee and Stuckatz (2024), in a comparative study of lobbying around the renegotiation of NAFTA (into the USMCA), show how MNCs adopt country-specific lobbying styles depending on where they’re operating. Drawing on an original dataset of over 800 lobbying entities active in both the U.S. and Canada, they find that even the same firms behave differently depending on local institutional logics.

In the U.S., lobbying centers on Congress, where political access is often brokered through external lobbyists and industry donations. In Canada, firms target the executive branch and bureaucracy, working more frequently through trade associations.

These patterns suggest that foreign firms don’t simply import strategies wholesale. They adjust. When lobbying in the U.S., they follow American norms: targeting congressional swing districts, hiring revolving-door insiders, adapting to the fragmented and election-driven tempo of legislative influence. When lobbying in Canada, they shift toward the more centralized, executive-led institutions that matter there. As the authors argue, MNCs don’t just operate globally — they lobby locally, tailoring influence strategies to political context.

In some cases, the adaptation goes a step further. In a follow-up working paper, the authors show that when firms face high-stakes threats to their cross-border operations—such as during the renegotiation of NAFTA—they don’t just localize their lobbying. They synchronize it.

What they term “complementary lobbying” emerges when MNCs lobby in multiple jurisdictions simultaneously on the same issue. A firm might meet with U.S. trade officials on Tuesday and Canadian regulators on Thursday, coordinating narratives, timing, and pressure points to maximize policy leverage on both sides of the border.

This strategy isn’t cheap. It requires more staff, more information, and more coordination. But when firms have supply chains that span the U.S. and Canada, and those chains depend on the stability of trade agreements, the payoff can be worth it. During the USMCA negotiations, firms with deep cross-border footprints were eight times more likely to lobby in both Washington and Ottawa in the same quarter.

This was not the case during the TPP negotiations, which offered prospective market access but posed fewer risks to existing operations. The asymmetry is telling: when the threat is to a status quo that firms have built themselves around, they don’t just defend it domestically. They defend it everywhere.

How Supply-Chains Reshape Political Coalitions

The effects of foreign investment don’t stop at trade volumes or GDP growth. Over time, foreign firms that embed themselves in local supply chains begin to reshape the political landscape around them. They don’t just join existing coalitions. They help forge new ones.

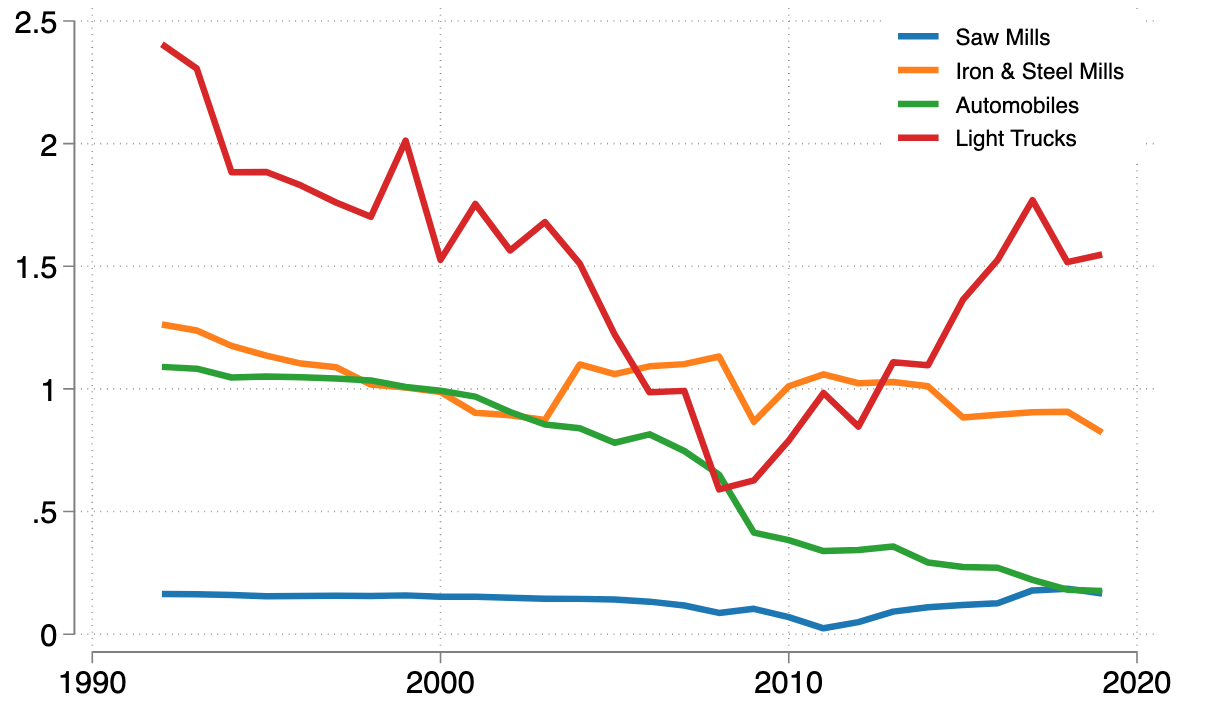

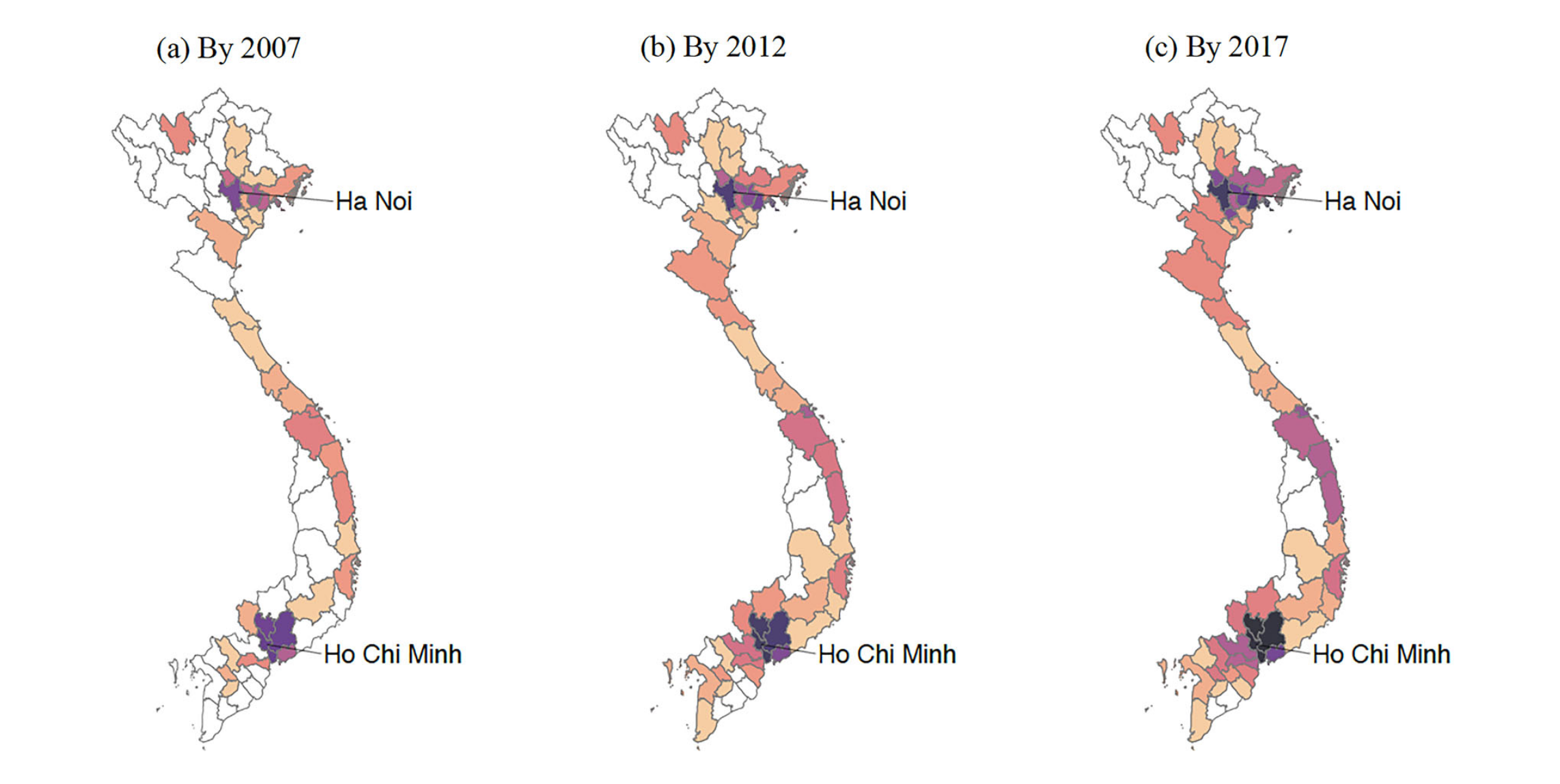

Kim et al. (2025) offer a striking example of this transformation in Vietnam, where over the last two decades, a surge in greenfield FDI—especially from South Korean firms like Samsung — has fundamentally rewired the country’s trade profile. The researchers begin by tracking every greenfield manufacturing project globally between 2003 and 2017 using proprietary fDi Markets data.

They then match these investments to highly granular Vietnamese customs records, mapping product-level trade volumes for each firm to 6-digit HS codes. This is remarkable data collection. It yields not only a portrait of where FDI goes, but also what it produces and how those products subsequently move across borders.

After new FDI arrives in a given sector, the number of unique exported products jumps—on average, by more than 45 in the following year. Four years out, the volume of those exports increases by 90% compared to similar goods. Imports rise too, though more modestly. In effect, FDI doesn’t just increase production; it transforms what a country makes and trades.

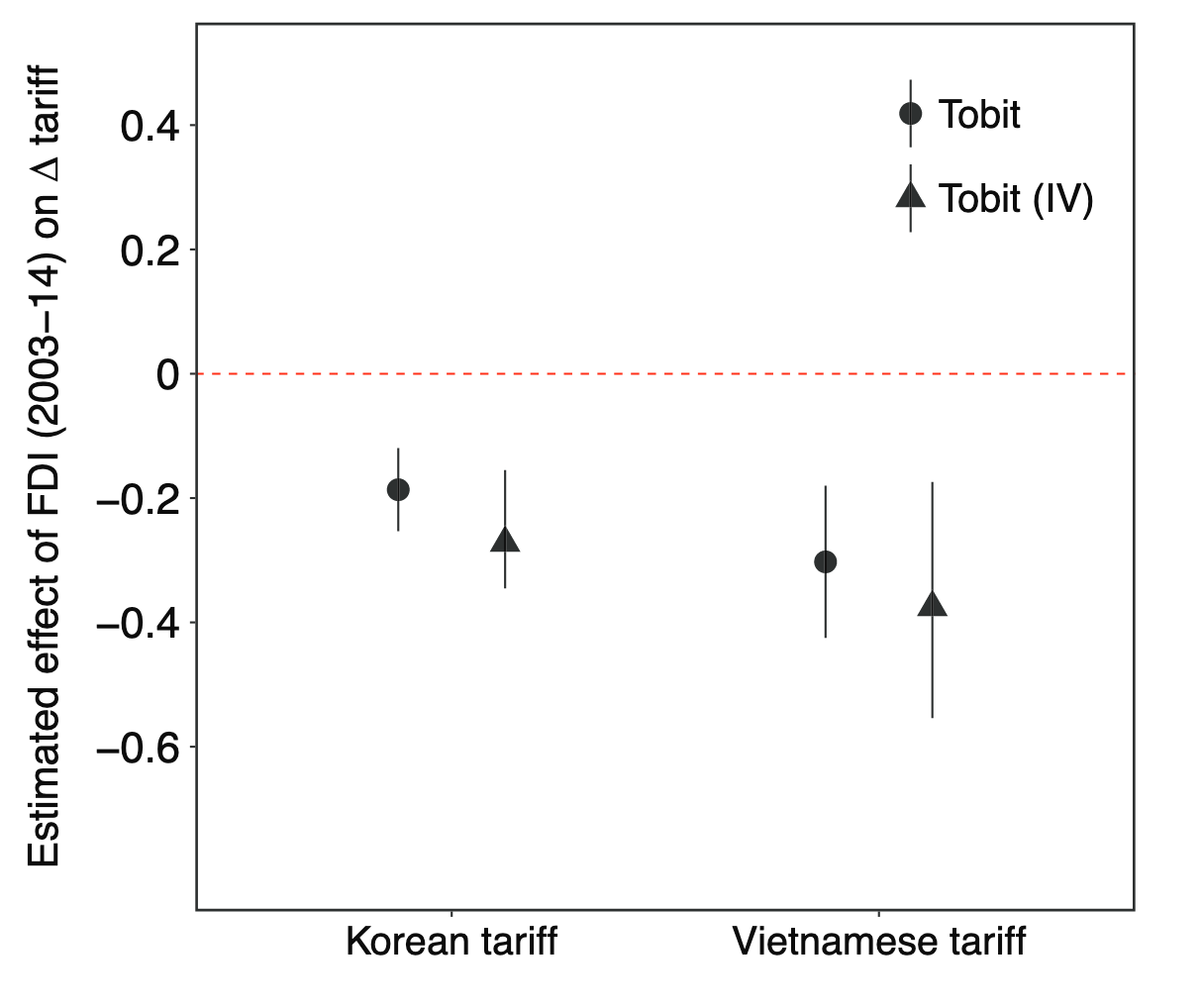

But the more significant political story lies in what follows. The authors trace how these MNC-linked products fared during the 2015 Korea–Vietnam Free Trade Agreement. The very products tied to multinational investment were more likely to receive favorable tariff cuts—by about 30% in Vietnam and 19% in Korea compared to similar goods. In short, FDI-linked products aren’t just made and traded more. They’re more politically protected. Policymakers have a reason to keep them flowing.

The mechanism behind this is coalition-building. In line with the findings on emissions at the top of this post, once a multinational sets up shop, it doesn't operate alone. It links with local suppliers, logistics providers, labor pools, and regulators. Domestic firms that might once have opposed trade liberalization now have skin in the game—either because they sell inputs to the MNC or because they benefit from its presence indirectly. This network effect reduces collective action problems and helps rally support for specific trade agreements that would have otherwise divided domestic constituencies.

Moreover, these coalitions are politically potent because they face limited resistance. The goods in question—smartphones, specialized inputs, precision components—are often highly differentiated. There’s little domestic production competing with them, and few losers to organize a backlash. That makes liberalization easier to sell and harder to resist. The politics of trade shift—not toward pure openness, but toward openness tailored to the supply chain.

This embeddedness has further implications, particularly for property rights. In another study, Johns and Wellhausen (2016) explore how multinational supply chains create not just political allies, but institutional shields. They argue that when MNCs are tightly woven into a host country’s production system, the costs of expropriating them are no longer borne by a single foreign firm. They ripple through the chain, hitting domestic suppliers, joint ventures, subcontractors, and local employment. That risk, in turn, creates informal but powerful deterrents.

To test this, the authors assemble a diverse set of evidence: cross-national data on investment arbitration cases, surveys of U.S. subsidiaries operating in Russia, and qualitative case studies from Azerbaijan and Romania. Across these disparate sources, the denser the supply chain, the stronger the informal protection.

Take the case of Lukoil in Romania. When the Romanian government threatened to nationalize a refinery amid a tax dispute, the Russian ambassador didn’t invoke geopolitics. He warned that such a move would disrupt “the whole technological chain” of Lukoil’s operations in Romania. A critical supply chain deeply entangled with the domestic economy. It worked. The refinery remained in private hands.

This is not just economic interdependence. It’s political insulation. As MNCs embed deeper into host economies, they don’t just gain allies—they change the rules of the game. Trade liberalization becomes more feasible. Expropriation becomes more costly. And the dividing line between foreign and domestic interests begins to blur.