How Supply-Chains changed International Lobbying

When we talk about trade politics, we still pretend the battle lines are clear: manufacturers versus service firms, exporters versus import-competers, labor-intensive sectors versus capital-intensive ones. That’s how we narrate the trade war, explain tariff exemptions, or predict industry coalitions. But that map is a relic. The reality is far messier—and far more revealing.

Today’s global economy is built on supply chains, not sectors. A tariff on Chinese steel doesn’t just hit Chinese firms—it raises costs for U.S. brewers, carmakers, and construction companies. One American firm might push for tariffs on electronics, while another in the same industry fights against them—because it imports parts from the very firms its competitors want penalized. As production fragments and firms build webs of cross-border dependencies, the old story of trade politics collapses. Globalization hasn’t just changed what firms want—it’s changed who lobbies, what they lobby for, and how they organize politically.

How Global Production changes Lobbying Participation

The shift toward international integration — especially in the post-1990s period — redrew the map of who lobbies, on what issues, and why. Where traditional accounts of trade politics focused on industry-level interests (exporters vs. import-competers), new research illustrates the granular terrain of firm-level lobbying, driven by global operations and product-specific stakes.

In-Song Kim and Helen Milner (2019) provides one of the clearest pictures of how firms’ political behavior changes once they become multinational. Using a difference-in-differences design on all publicly traded U.S. firms from 1999–2019, the authors track what happens when a firm crosses the threshold from domestic to multinational. Their empirical strategy hinges on constructing a binary measure of multinationality using firms’ foreign pre-tax income (from Compustat) and cross-validating those against qualitative evidence of foreign expansion.

*Not only do newly multinational firms increase their lobbying expenditures by roughly 50% within two years of going multinational, they also broaden the scope of issues they lobby on, particularly in foreign economic policy.

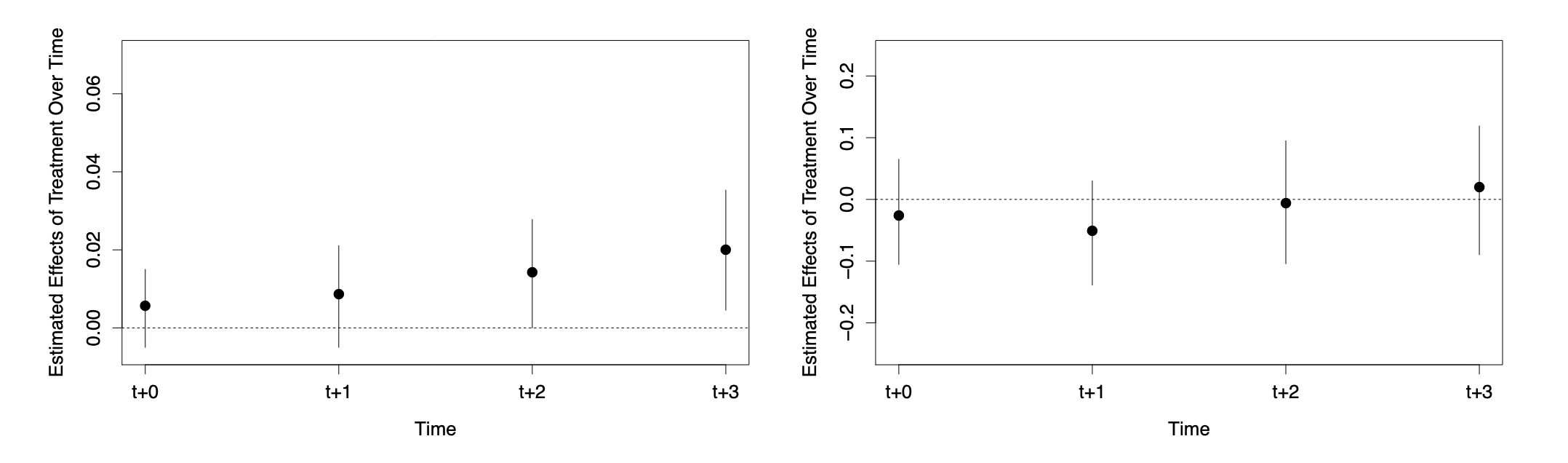

Firms become especially more likely to lobby on tariff issues once they go multinational, suggesting a clear link between global exposure and targeted trade lobbying. The left panel below shows that increased tariff activity. The authors cleverly contrast it with lobbying on taxation, the right panel, and show no changes in behavior in what is generally thought of as the most important business issue.

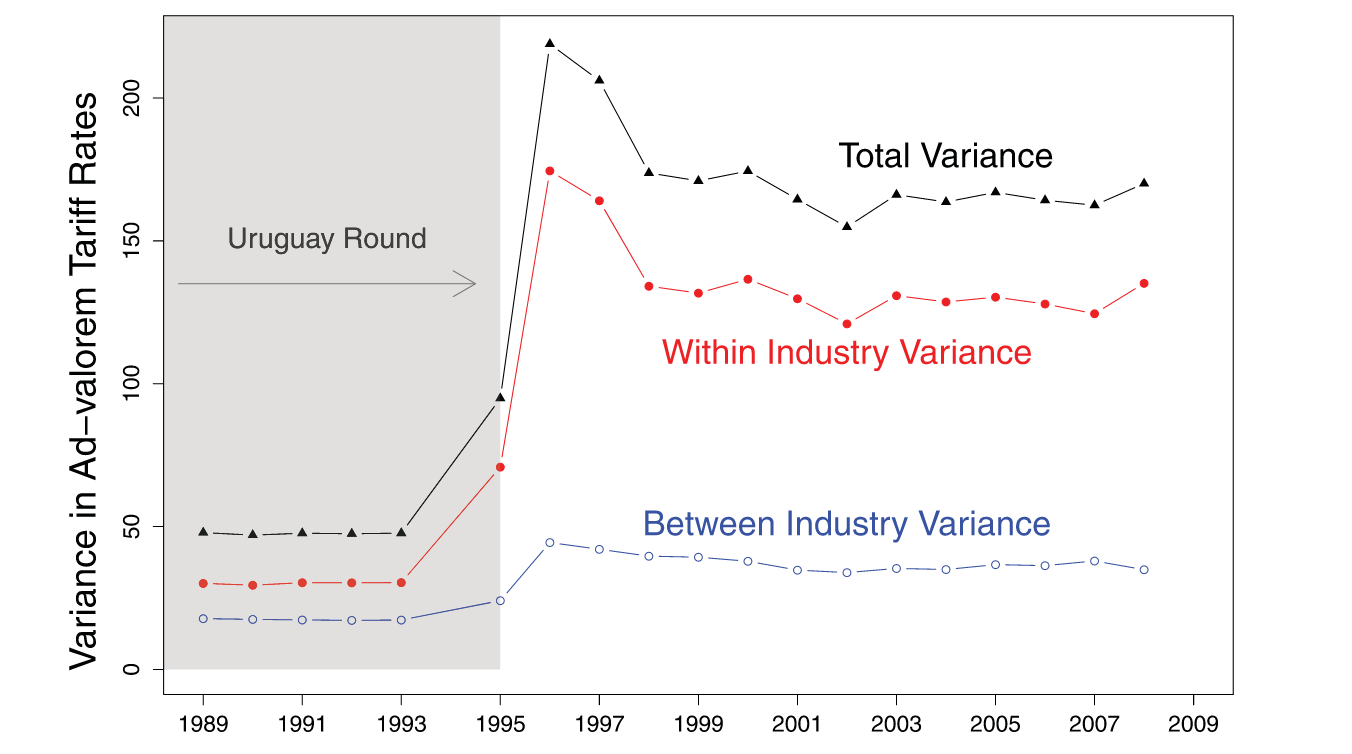

The paper above develops a key insight from Kim's previous work (2017). He focuses on the fact that tariff rates vary enormously not just across industries, but within them usually hinging on minute product differences. For instance, within the same industry, flashlights (HS8 85131020) face a 12.5% tariff, while “other electric lamps” (HS8 85131040) are taxed at just 3.5%. These gaps are not accidents—they reflect targeted lobbying by firms with unique products and less substitutable competition.

This variation is visualized in Kim’s analysis, which shows that most of the variance in U.S. MFN tariff rates arises within industries:

This matters because differentiated products reduce the collective action problem. Firms that export unique goods have much stronger individual incentives to lobby and less fear of intra-industry competition from liberalization. This helps explain why we increasingly see individual firms, not associations, driving trade lobbying.

The importance of the ability to act collectively comes through in Ian Osgood's (2021) a sweeping dataset covering over two decades of lobbying and campaign finance activity. Pro-trade lobbying is disproportionately driven by large, globally integrated firms.

Across every major trade initiative since the early 1990s—NAFTA, TPP, Fast Track authority, pro-trade coalitions have been formed and led by a relatively narrow set of powerful multinationals. Of the over 4,300 firms that publicly supported trade liberalization, just 301 publicly opposed it. These firms also account for 68.5% of all corporate PAC contributions from goods-producing firms.

Moreover, Osgood finds that firm preferences toward specific trade agreements are shaped not just by their global exposure in general, but by the specific countries in which they operate. A firm with a subsidiary in Vietnam is far more likely to support a U.S.–Vietnam Free Trade Agreement than one without.

This is exactly the dynamic explored by Zeng et al. (2020), who argue that deep supply chain integration alters trade preferences.Using TPP-related lobbying by Fortune 500 firms, they show that firms with higher global value chain (GVC) linkages are much more likely to lobby for liberalization. GVC-linked firms see tariffs not as tools of protection, but as disruptions to complex webs of production that span borders. These findings are affirmed in more qualitative approaches such as Meckling and Hughes's work on the solar industry.

Even more ambitious in scope is the work of Leo Baccini and his colleagues (2025), who argue that it’s not just that GVCs create preferences for liberalization. They actively shape the depth and content of trade agreements. Using a very clever instrumental variable strategy based on the maximum size of container ships (which can only be docked at deep ports), they isolate exogenous variation in trade flows and tie it to the signing of deeper, broader PTAs.

They find that GVC integration — both backward and forward—raises the probability of deep PTA formation by up to 30%. The political economy of trade is being driven by firms not just demanding open markets, but also lobbying for rules around services, investment protections, and regulatory cooperation—hallmarks of the 21st century trade agenda.

Supply-chains reduced trade conflict

More imports, more offshoring, more potential for domestic backlash should trigger international trade tensions. Yet many forms of protectionist pressure have waned, especially among the very firms one would expect to be on the front lines. The reason, according to a new body of research, is the growing reach and complexity of global production networks. Firms embedded in global supply chains are less likely to push for protection, less likely to retaliate, and more likely to accommodate even when foreign competitors have unfair advantages. Supply chains, in short, don't just shape production. They reshape the room for cooperation.

A foundational example comes from Margaret Peters’ work (2014, 2015) on immigration. Her argument is deceptively simple: trade openness substitutes for immigration pressure. When firms face barriers to offshoring, they rely more on low-wage labor at home and thus lobby for more permissive immigration policies. That's particularly for low-skilled workers. But once they can offshore jobs or automate production, their need for labor drops. So does their support for open immigration.

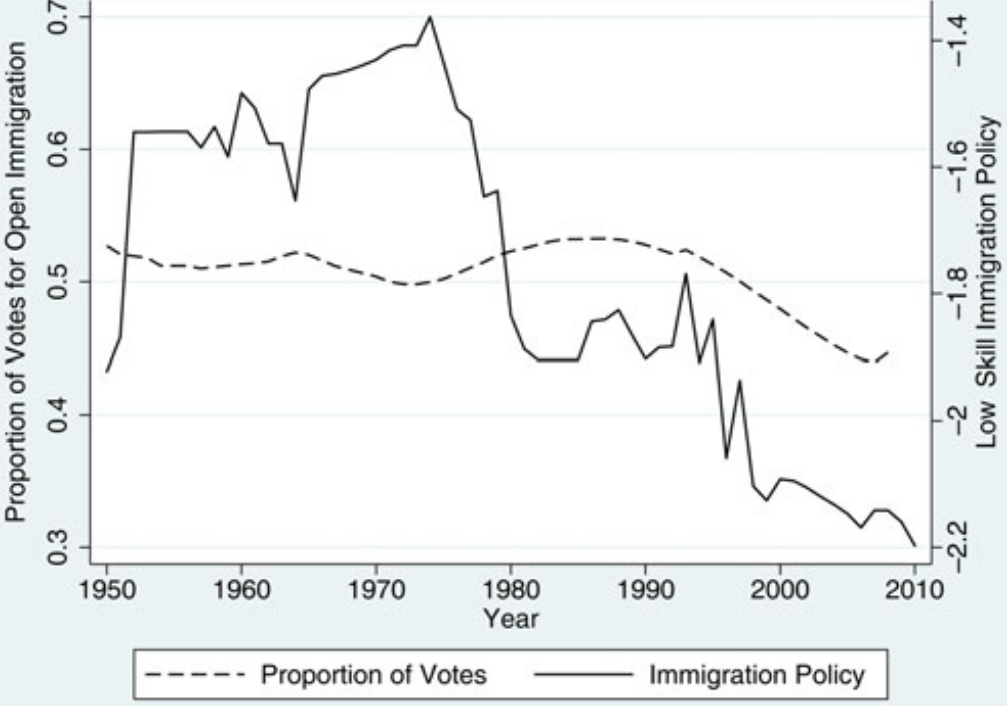

Peters tests this logic using data on U.S. Senate votes on immigration from 1950 to 2010. As she shows, pro-immigration votes peak during periods of trade closure, i.e., when domestic firms still depend on low-skill labor. But as trade opens and firms gain the option to move overseas or automate, their support for liberal immigration declines. Figure 1 from her 2014 article captures this evolution vividly:

Importantly, this isn’t just about public attitudes or party politics. It’s about which firms lobby, and why. Peters links lobbying records (1998–2011) with measures of firm tradability and mobility. Firms that are tradable and mobile (i.e., can offshore or automate) lobby far less on low-skill immigration than those that are immobile or sheltered from trade. It's a stark gap. 14% of lobbying by non-tradable, immobile firms focuses on low-skill immigration, compared to just 4% for tradable, mobile firms. Trade openness reduces lobbying intensity because the firms that would benefit most from cheap labor simply leave.

This pattern repeats in other domains. Ryan Weldzius investigates a different form of economic conflict: government intervention in foreign exchange markets to artificially weaken a country’s currency in order to boost exports and discourage imports. The "currency manipulation" that sits at the heart of US-China conflict. In the 2000s, many export-led economies (Malaysia, and Thailand) engaged in aggressive manipulation. But this practice has all but disappeared. Weldzius argues that the rise of global supply chains cause that drop.

As countries become more reliant on foreign inputs for production, devaluing their currencies becomes riskier. It makes imports more expensive. That hurts domestic firms that rely on imported components. Using data on 143 countries between 2000 and 2018, Weldzius finds a robust negative relationship between integration into global production networks and currency intervention. In short, when firms depend on foreign inputs, manipulating currency becomes self-defeating.

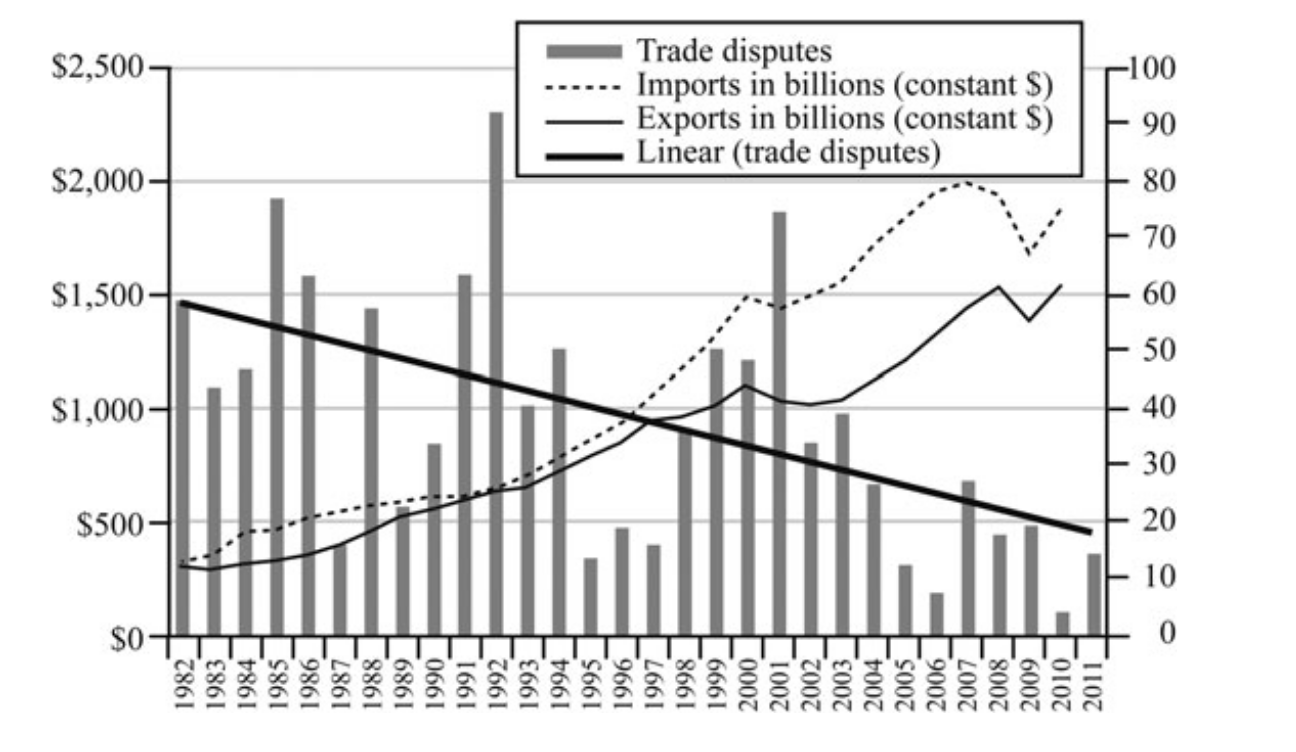

The most direct expression of this conflict dampening shows up in the realm of antidumping (AD) disputes. They are a type of trade remedy that allows domestic firms to request tariffs on foreign products being sold below fair market value. In the U.S., these filings have long been a favored tool of protection. But as Jensen et al. (2015) show, AD petitions have collapsed, even as import competition has soared.

The key, once again, is supply chains. Firms that are integrated into global production networks especially through intrafirm trade (the exchange of goods between a firm’s parent and its foreign affiliates) are far less likely to file trade complaints. If your subsidiary in China ships parts to your plant in Texas, slapping tariffs on Chinese goods hurts your own bottom line. As more firms develop these internal linkages, their appetite for AD filings falls.

The authors back this up with firm-level data from the BEA Benchmark Surveys (1989–2009), linked to AD filing records. Their analysis shows that firms with vertically integrated FDI (foreign direct investment where a firm establishes or controls production facilities abroad to manage different stages of the supply chain) are significantly less likely to file for trade protection, even in the face of undervalued currencies. The logic is simple but powerful: protection hurts when it targets your own supply chain.

And it’s not just individual firms that stand down. As more MNCs become globally embedded, it becomes harder to organize the 25% industry support required to trigger an AD petition. The politics of protection break down not because coordination becomes infeasible. As Jensen et al. put it, “the rising share of economic activity accounted for by firms with global affiliates makes organizing a coalition increasingly difficult.”

These studies point to a shared conclusion: integration disciplines protection. Firms that span borders have more to lose from retaliation, more tools to adapt, and less incentive to lobby for confrontation. Policymakers take notice. Whether it’s immigration, currency policy, or trade disputes, the message is the same: the more tightly supply chains bind firms to the global economy, the less they demand walls.

But supply-chains also create narrower interests

As global production has become more modular and distributed, so too has the logic of firm preferences in trade politics. The traditional divide between exporters and import-competers, or even between multinational and domestic firms, can’t fully explain the new coalitions emerging in trade debates. What ties these groups together isn’t sector, size, or even direct exposure. It is supply-chain participation. These links, especially when built around long-term, specialized relationships, foster a distinct kind of interdependence — one that turns some firms across industries into allies, and traditional allies into enemies.

Hao Zhang (2023) offers perhaps the most comprehensive look at this dynamic. [Drawing on an enormous dataset of over 3 million supply-chain relationships from FactSet and matching them to 82,000 lobbying disclosures], Zhang finds that firms embedded in shared value chains are far more likely to act together politically](tab:https://gsipe-workshop.github.io/files/GSIPE_HaoZhang_1020.pdf). These “GVC partners” don’t just share economic dependencies; they lobby on the same bills, hire the same lobbyists, and coalesce into formal trade associations—even when they span entirely different sectors.

This is not accidental. Because modern supply chains often involve relationship-specific investments like customized components, tailored logistics, or co-developed design, firms have strong incentives to coordinate. The result, as Zhang puts it, is strategic complementarity: the more one firm lobbies on a given issue, the more it pays off for its GVC partners to do the same.

These are not hypothetical dynamics. Take the U.S. apparel and footwear industry during the China trade war. Classical trade theory would expect such a labor-intensive sector to demand protection. And firm-level models might predict fragmented lobbying, with large exporters quietly pushing for liberalization. Instead, what emerged was a coalition of over 170 brands — including Nike and Foot Locker — jointly opposing tariffs. These weren’t just exporters — they were participants in a tightly knit production ecosystem, and their interests were aligned as such.

This explains why firms that don’t even produce similar products can still coordinate politically. Zhang shows that when two firms share foreign suppliers, they’re significantly more likely to lobby on the same bill and hire the same lobbying firm, especially in industries like retail, logistics, and finance — the connective tissue of supply chains.

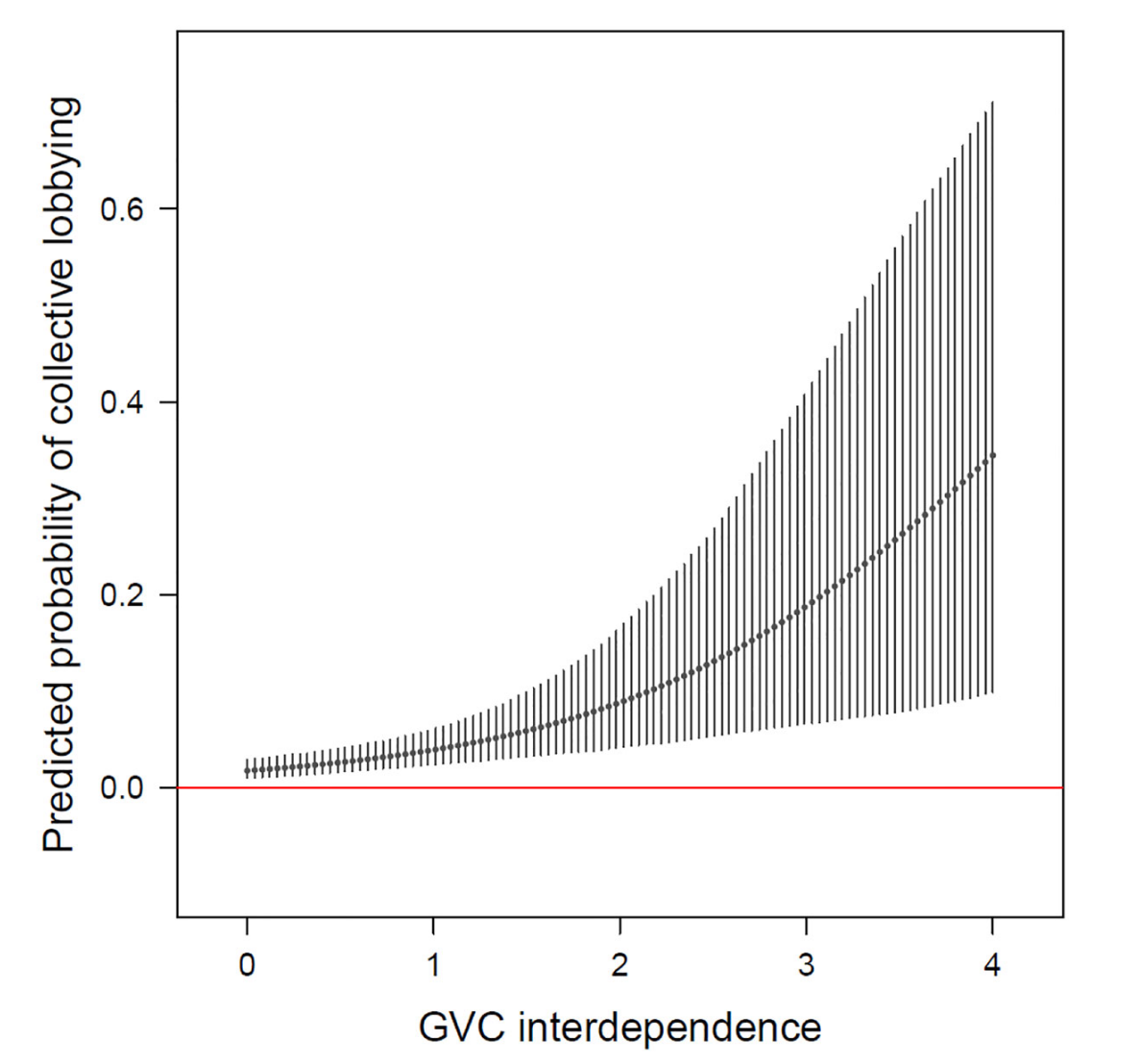

That logic also explains how trade associations are being transformed. Once seen as relics of old industry politics, they’re increasingly becoming vessels for GVC-based coalitions. Zhang finds that in industries with higher GVC interdependence, the probability of collective lobbying rises from nearly 0% to over 30%.

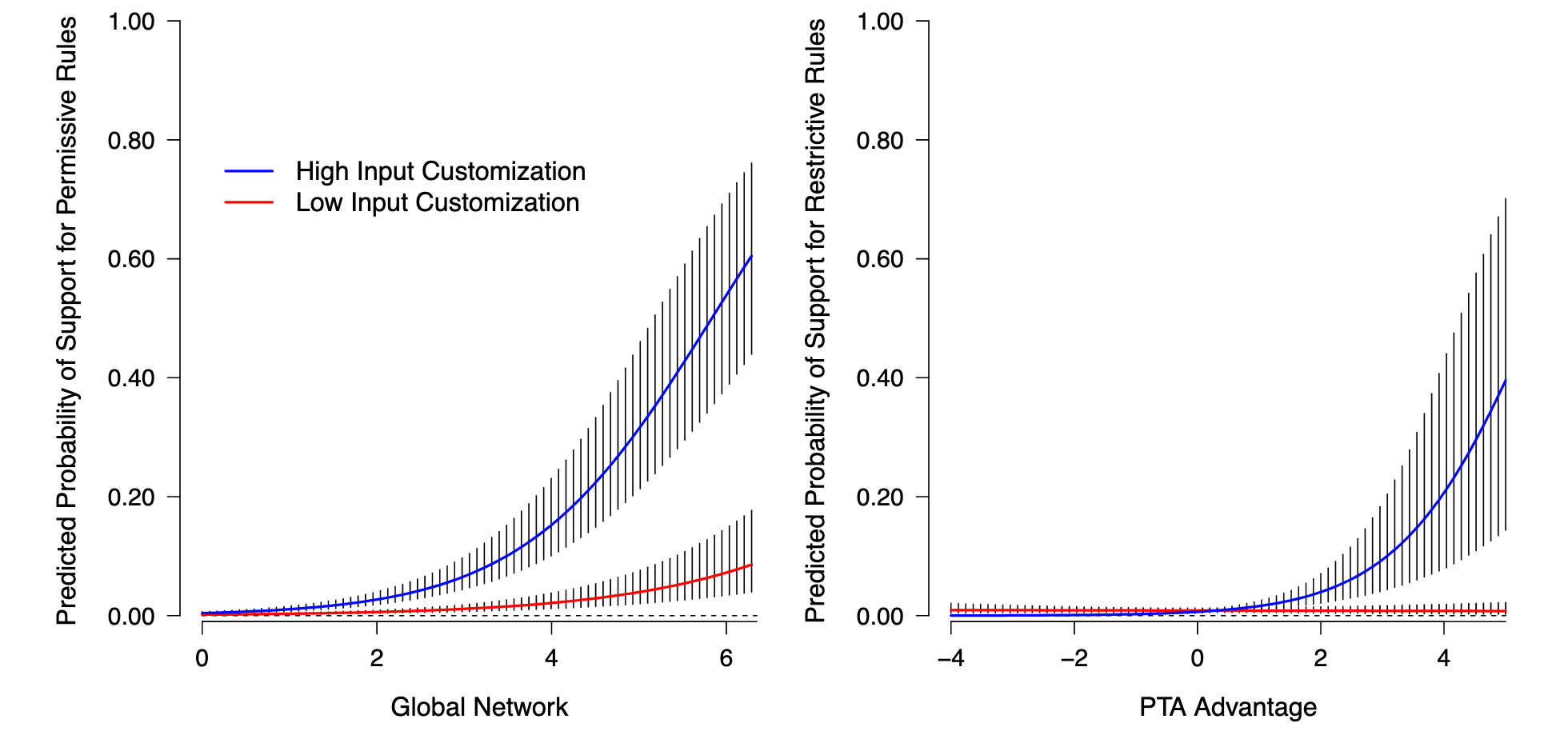

Laaker (2025) adds an important layer: supply chains don’t just create alliances, they create specific cleavages within industries. Focusing on rules of origin in trade agreements, Laaker shows that firm preferences split sharply depending on their position in the value chain and their degree of input customization. For example, during NAFTA negotiations, Xerox lobbied for restrictive rules that would exclude rivals who relied on offshore suppliers, while Canon pushed for more permissive ones.

What matters isn’t whether a firm is “pro-trade” or “anti-trade,” but whether a particular rule helps or hurts their specific supply chain configuration. Laaker’s analysis of lobbying positions across 5,770 firms confirms this: the more customized a firm’s inputs and the more global its sourcing, the more likely it is to support permissive rules of origin. Unless it has a competitive edge in the PTA market, in which case it prefers restrictions.

A similar dynamic plays out in Zeng (2021), who investigates lobbying over China trade policy between 2006–2016. He finds that firms engaged in vertical FDI — investing in overseas production facilities — are especially likely to lobby, compared to those that only source inputs or export final goods. Sunk costs drive political action. Firms that have physically invested abroad face much higher switching costs, so they have more reason to advocate for stable trade relations.

Yet deeper integration doesn’t always yield more lobbying influence. In a related study, Eldes et al. (2025) explore which firms were granted tariff exemptions during the U.S.-China trade war. Among the 52,746 exclusion requests, they find that large firms that lobbied were generally more successful, except when they had subsidiaries in China. Even among lobbying firms, those with Chinese affiliates were significantly less likely to win exemptions, suggesting that policymakers penalized firms seen as too deeply tied to a rival power. Integration, in this case, became a political liability.

These studies point to a broader shift: the logic of trade politics is no longer national or even sectoral. It is firmly networked. Companies connected by supply chains develop specific, shared interests, shaped by how their goods are made, where their partners are located, and how policy ripples across production stages. The politics of trade today is not about “business vs. labor” or “manufacturing vs. services,” but about whose supply chains get protected, and whose get cut.