The Business Politician: Motives, Methods, and Private Gains [v1]

President Donald Trump is an aberration on several fronts: his trade policy, his diction, his comfort with cruelty. But, more than any of his policy platforms, he touted his business instincts as a key reason he should be elected. Voters preferred his ability to run the American economy over Joe Biden, and we even have strong evidence that his reality TV persona fed into that view.

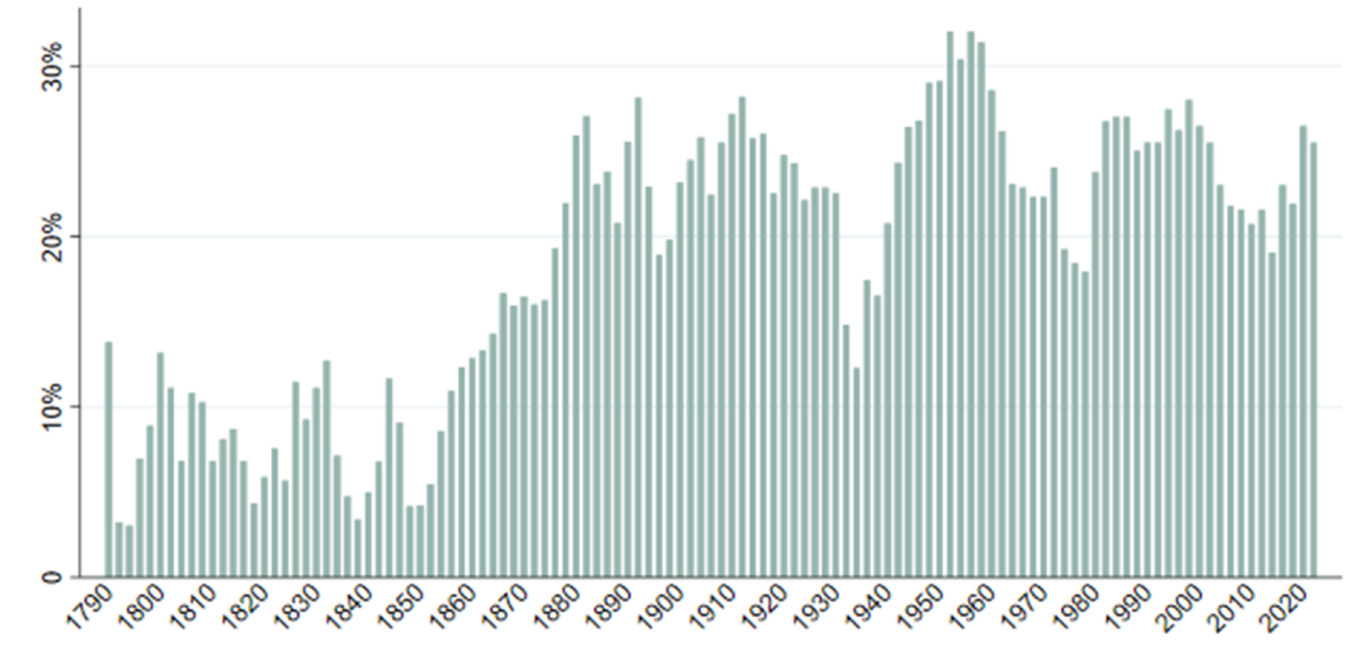

Yet his experience with branding, with brash management is hardly unique. CEOs and individuals with substantial experience in the private sector - as board directors or senior management - have become a growing trend across the US. As the Figure below shows, we are in not even the first, but a third era of American politics where businesspeople dominate the senate floor. Nearly 30% of the chamber is filled with individuals that tout that self-made success.

This type of entrepreneurial dominance is mirrored across different levels of the American government - close to the 32% of mayors have business backgrounds. But there isn't any American exceptionalism going on either. In Russia, businesspeople ran in 35% of mayoral elections between 2007 and 2016 and won 22.5% of them. If we look at the NATO members, 18.65% of heads of states that served between 1952 and 2014 had pre-office business experience.

But you are probably thinking - like I assume President Trump would be thinking - this simply isn't the right comparison group. Trump is no ordinary businessman. He's a billionaire. And billionaires may now be the group that is most asymmetrically represented in political office.

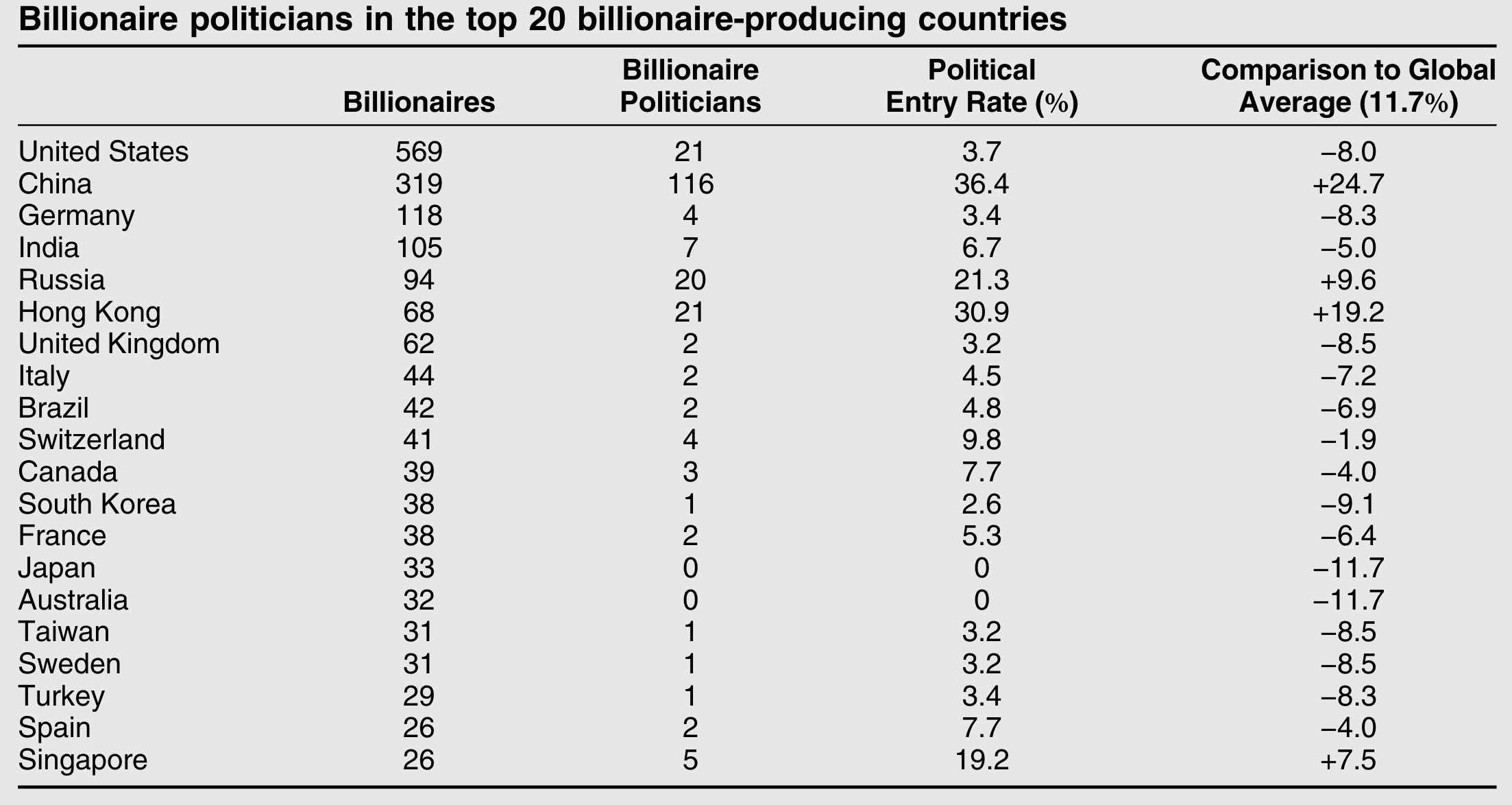

A global study by Krcmaric, Nelson, and Roberts found that 11.7% of billionaires have held or sought formal political office, and when informal or quasipolitical roles are included, the number surpasses 15%. That number tracks at a micro-level as well - possibly the most famous pro-business billionaire lead coalition was formed by telecom tycoon Thaksin Shinawatra in Thailand. Of the 100 richest individuals in the country, 13 were part of the administration.

This article is the first of two posts examining the causes and consequences of business-politicians. In this review, we'll explore why businesspeople run, how they win, and what benefits they (and their firms) derive once in power.

Why Do Businesspeople Run for Office?

It's possible that wealthy business owners turn to politics because they've made enough money and they want to directly give back. Maybe they are part of a broader ideological project - some billionaire politicians certainly have been. But a host of recent work in political economy indicates that running for office is driven by a mix of self-protection and economic ambition.

Holding office can be a highly effective wealth protection strategy when you are dealing with a state, or a set of bureaucracies, that are willing to abuse their power. In her multi-method study of business-politicians in China, including interviews with over 100 entrepreneurs, Yue Hou neatly summarizes the logic:

First, compared to strategies that rely heavily on informal political connections, the strategy of using one’s legislator status to protect property can be purely formal. An entrepreneur does not have to go through any informal exchange to establish or enhance his political capital once he has a seat in the legislature.

A second distinction is its relatively cost-effective nature. Although securing a legislative seat might incur high costs, once an entrepreneur has a seat in the legislature, his position serves as a signaling mechanism to deter potential predators without any additional investments.

Entering politics can then be a credible means of aligning oneself with the ruling elite to minimize risk. And that has positive spillover effects. Billionaires in China join institutions like the National People's Congress not just for ideological reasons, but because such roles offer a stamp of approval - investors don't think you're allowed in unless you've been deemed useful and thereby probably profitable.

Political office can then be seen as an insurance mechanism against the multiple-hands of the state. But that's a largely defensive view. In their study of businessmen candidates in Russia, Gehlbach et al. (2010) show that the likelihood of businessmen entering politics is influenced by the range of institutional quality. Leveraging the fact that Russian regions have diverse levels of media freedom and transparency, they show that businesspeople are far more likely to run when these institutions are weaker. Voters will be less able to detect corrupt behavior or broken promises. In other words, an effective businessman sees opportunities to make money and takes it: political office can be see as that kind of opportunity.

These logics echo the cross-country findings on billionaires - they are far more common in autocracies than democracies. 29% of billionaires in autocracies get directly involved in politics compared to 5% in democracies.

But what do traditional political parties make of this business infiltration? Plenty of election politics involves clientelism - quid pro quos with voting groups that help you get elected. That type of mobilization, the credibility of those promises, costs a lot of money. Arriola et al. (2022) show that in the case of Zambia, being a business owner increases the likelihood of party recruitment by 56%. These candidates are five times more likely to report having to bribe party officials for a nomination.

A Businessman's Political Edge

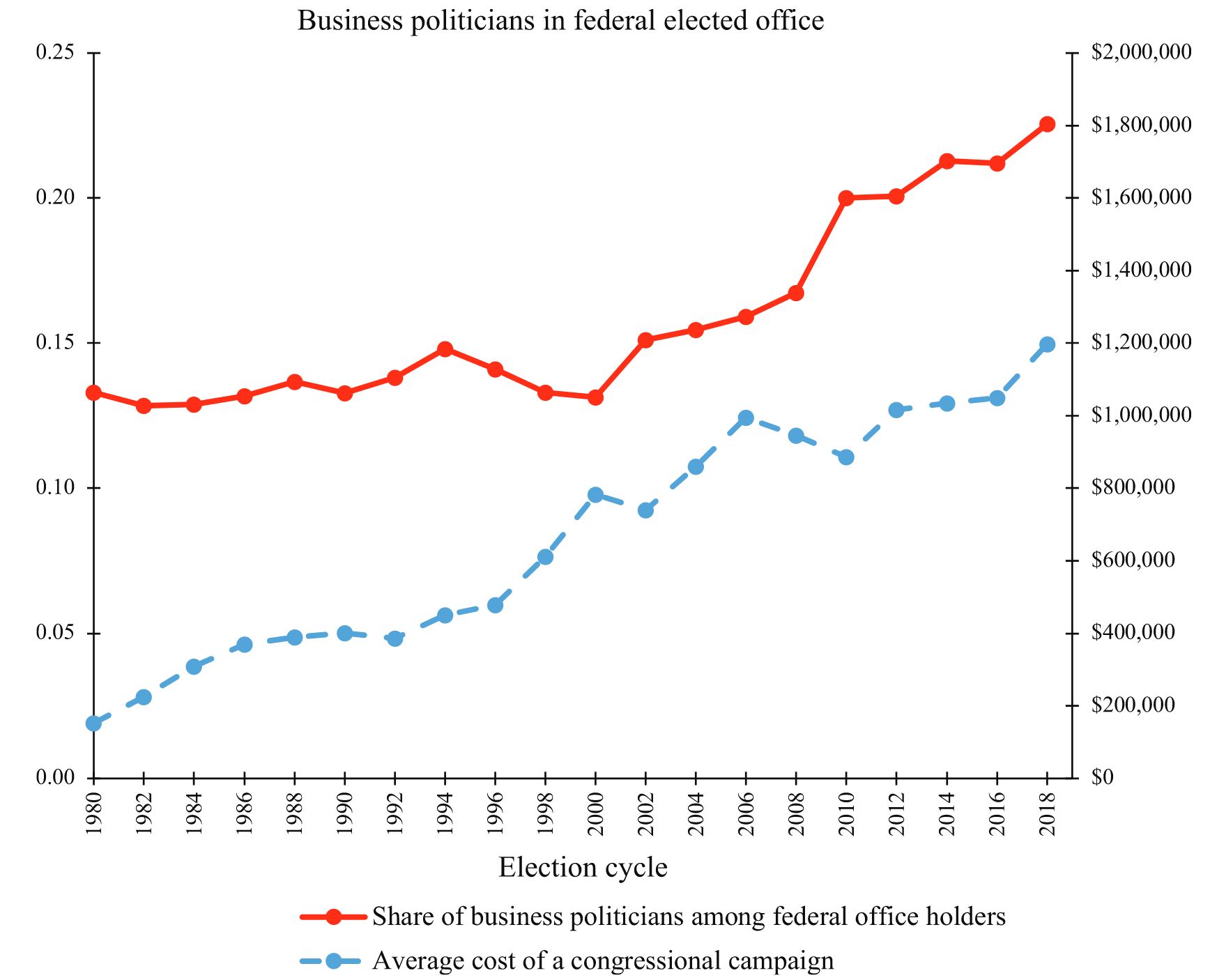

Comparing Zambia with the likes of the United States and Russia might feel a bit farfetched, but this potential for businessmen funding their own campaigns is a central reason seen their influx into American politics. 24% of business candidates for federal office contributed at least $1 million to their own races, compared to just 4% of non-business candidates. As the figure from Babenko et al.'s (2023) remarkably in-depth study of executives in American politics shows, the latest wave of business-politicians is highly correlated with increasing campaigning costs.

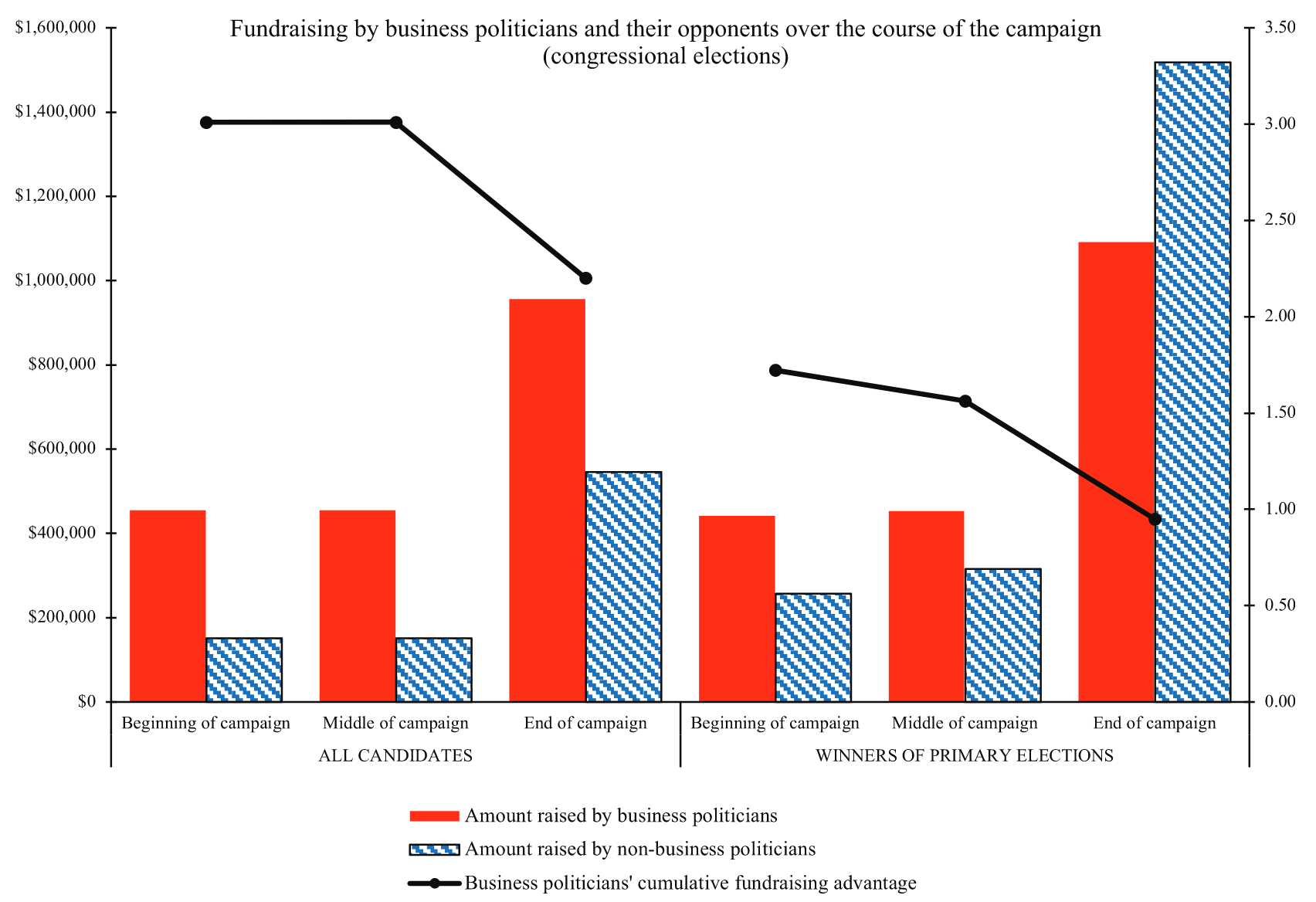

They further show that these individuals are able to out fundraise conventional politicians particularly in early parts of their campaigns, which political science sees as one of the keys to electoral success. It helps to have a rolodex of CEO friends.

But it isn't just their friends doing the work. It's their firms. Arguably the most astounding finding in their paper is that companies associated a business-candidate spend 6 times to support their leader than the average politicians. In 77.6% of the cases, the business-candidate is the highest financially supported candidate by the firm.

Money isn't enough to win elections. You still have to run, have to have some kind of message. Owning a media company will surely help with that. But the most common tactic is for business-candidates to label themselves as problem solvers. Unique individuals that can break gridlock, who will not be beholden to special interests. That framing is inevitably going to resonate in times of crisis, when voters are disillusioned with traditional politicians. Studies show that business candidates are more likely to run, and win, during economic downturns or periods of fiscal strain.

Views on business and its effective role in society inevitably oscillates. While some might see business acumen as a sign of competence other could see it as a recipe for corruption—sometimes even corruption that voters view as beneficial. Justesen and Markus (2024) lay out four potential strategies business-candidates has use to garner voters. They could appeal to that acumen. They might simply be well known already. They could seek to exploit social divides like along race. Or they could engage in clientelistic practices - that de facto vote buying we discussed in the previous section.

They run a survey experiment in South Africa, priming individuals with these different strategies - clientelism has the strongest positive effects in increasing a candidate's popularity. The effect is strongest on , when a voter is not materially well off. Previous fame and competence do quite little while a racial frame can have a backlash effect.

Businesspeople have a fairly impressive electoral track record. They win just under 60% of federal offices that they run for per Babenko et al. (2023) with a drop to roughly 50% between 2002 and 2016. don’t just enter politics; they often win. Only 8 out of 242 billionaires that sought elected office lost their campaigns according to Krcmaric et al.'s study. Interestingly 6 of these 8 losers were American.

The Benefits of Office: Firms and Fortunes

Ok, now we're ready for the elephant in the room - once elected, do the firms that a politician is connected to benefit? Across contexts, the answer is a resounding yes. The most famous, and certainly the most well-cited, study on this is by Mara Faccio (2006) who collected data on 20,000 firms across 47 countries. Some 541 companies had connections representing 8% of global stock market capitalization. Note that she also codes companies that have close relatives in office. Nonetheless, she finds positive impacts on firm value across the board - the benefits to the firm increase with a higher office (legislator vs. prime minister, etc).

In the U.S., the election of a business executive to federal office is associated with an average stock bump of 1.4% for their company, amounting to nearly $200 million in value. Remarkably, these results do not just impact the politician's firm, but has further spillover effects on the industry that the politician works/worked in.

Studying the stock market returns of the 10 companies most similar to the politician's firm, Babenko et. al (2023) find clear wins with the effect ranging between an increase 0.6% and 0.9% of stock price value had the politician not won office. I find this particularly interesting as the market seems to interpret the politician winning not as a clear sign that they will just be better at channeling money to their firm, but that instead regulatory change for the industry is most likely to drive de facto personal gains. With that in mind, Industry peers also benefit, suggesting broader market confidence in regulatory favoritism.

David Szakonyi is the political scientist that has done the most in increasing our understanding of businessmen in office. He studied the performance of 2,703 politically connected firms in Russia after collecting data on the backgrounds of 12,000 regional candidates. To identify the impact of the business-politician, he used a Regression Discontinuity Design. The idea here is that when elections are super close it's basically a coin toss.

So if a business-candidate won that coin toss, they randomly gained office, allowing us to isolate the effects of office on their firms: they experience a 60% increase in revenue and a 15% rise in profit margin over the course of their tenure. These firms are also 40% more likely to win state contracts, underscoring the value of access.

In China, legislatures have even less power than in Russia. The National People’s Congress (NPC) is notorious for existing just to ritualistically approve the central CCP mandates. As I mentioned in the opening section, even these "rubbser stamp" positions bring a reputation boost that enhances investment and business ties. Companies linked to NPC deputies see returns increase by 1.5 percentage points and profit margins improve by up to 4 points.

The mechanisms vary: some firms benefit through enhanced reputation and investor confidence; others through procurement favoritism or regulatory changes. In Thailand, firms tied to tycoons who attained top office during Shinawatra's term outperformed their peers by over 160%, largely due to favorable policy shifts like tax breaks and market entry barriers.

Blurring the Public Private Divide

We have consistent evidence of firm-level gains and regulatory favoritism raises red flags about conflicts of interest and rent-seeking. Moreover, the incentives to enter politics often stem not from a desire to serve, but from the benefits conferred by office: protection, prestige, and profit.

In weak institutional environments, these incentives are particularly pronounced, but even in advanced democracies, business politicians often exploit campaign finance loopholes, control over media, and ideological branding to secure power.

The self-interest underpinning business politicians’ behavior does not necessarily make them less legitimate As the next post will explore, their influence on domestic and international policy is, however, more controversial.