The Economic Value of Tax Havens

It’s in the name, right? When you hear the term “tax haven” one of two stories likely go off in your head. Either corporate behemoths like Apple and Amazon spring to mind as they shield their profits to keep their taxes lower than yours or mine. Or you think of money launderers, drug dealers, and arms traffickers illicitly moving their money around the globe without detection.

There is some truth to both these images. Apple and Amazon are synonymous with tax avoidance where individuals and companies use legal methods like shell companies and tax treaties, to “book” where they are making profits to minimize how much taxes they owe. The “dealers” version exemplifies tax evasion: situations where individuals or companies use illegal methods like underreporting the money they make.

We owe a lot of our knowledge on the offshore world to the work of French Economist Gabriel Zucman who used pioneering methods, looking at distortions in trade balances, to estimate the size of money flowing through places like the British Virgin Islands and Mauritius. We’re talking about 8-10% of global wealth. About 50 Mark Zuckerbergs or roughly $10 trillion.

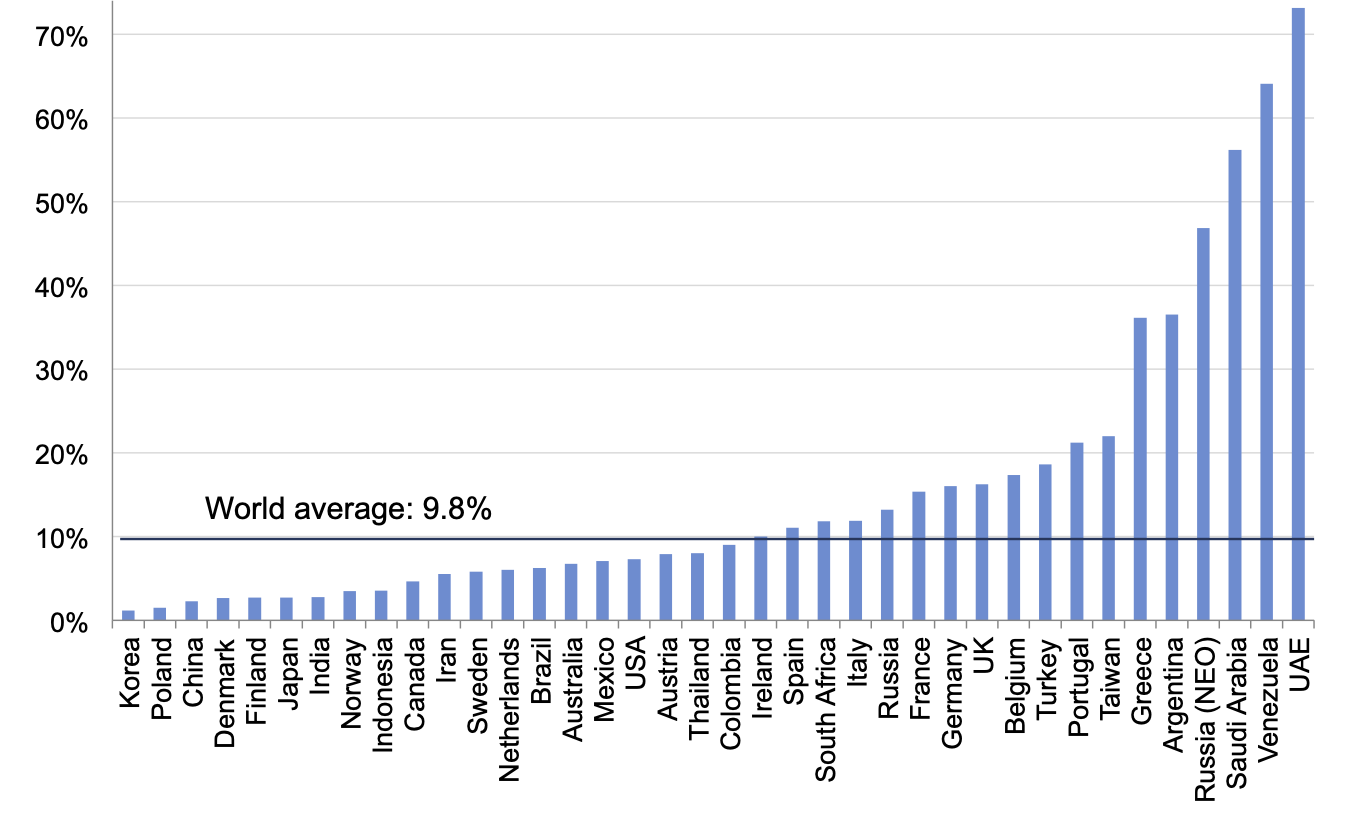

But when you look at the data produced by Zucman and his colleagues a few anomalies standout. Consider the figure below which shows the countries whose largest share of national wealth is held “offshore” in tax havens. Several of the countries to the far right – the countries whose governments and citizens are in theory the biggest losers – don’t actually have high tax rates like Saudi Arabia or have their own sub-national jurisdictions that allow individuals to reduce their tax burdens like in Russia (like how Delaware is the base for all American companies in the US).

The last decade has seen a renaissance in social science research on tax havens that helps us understand why tax havens are rarely about taxes these days. The TLDR is we need to think about “offshore jurisdictions” or “tax havens” as providing people a menu of legal options that they lack at home. This can include additional economic benefits like the ability to more effectively and efficiently raise money. Or their strong legal environments also just make them important places to keep your money away from a government that’s going after you – more about secrecy and protection than keeping taxes low.

The Standard Story (that does really matter)

A few things unite tax havens. They have very low tax rates usually for both corporate and income tax. They promise political stability – no one wants to move their money to a country at risk of a coup. And they are usually most successful when they also have strong links to major financial centers like New York or London. The latter is a major reason why places like the British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands are popular destinations – a serious conflict would not only first go through a high rule of law destination (the haven) but a challenge would work its way up into the traditional UK courts. The ties also become key when we think about the non-tax benefits of these usually island states.

These jurisdictions are often places with few economic opportunities – small populations not blessed with natural resources – so they’ve decided on a growth model: take a scrap of the revenues for multinational corporates and plutocratic individuals even if it diminishes some of the tax base of larger economies. Those guys are big. They have other options.

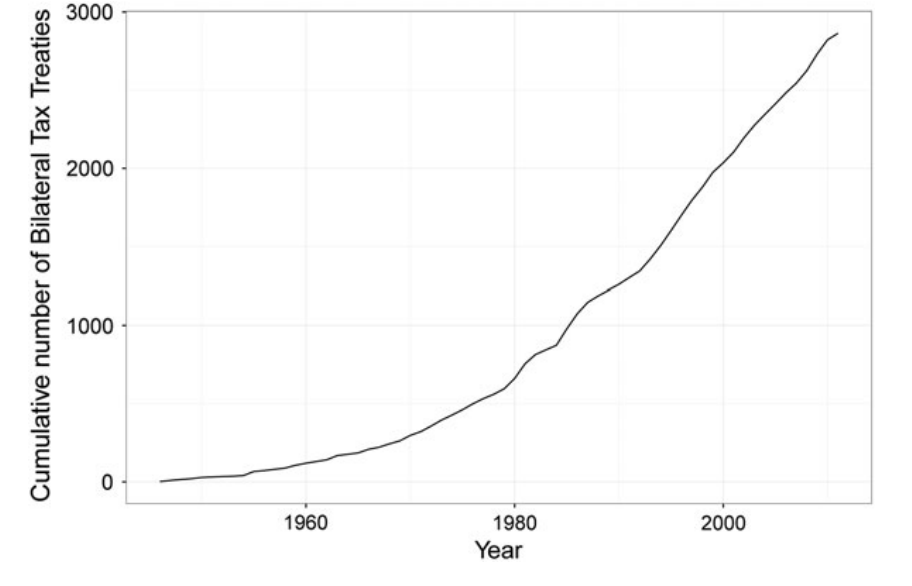

So the model is inherently international and relies on the way we’ve decided to govern taxes internationally. Unlike say in international trade, where we have the World Trade Organization (WTO, RIP), we have a massive number of bilateral tax treaties (BTT). So these only apply between the pair of states that are signing the agreement. Picking up in the 1960s, there are now more than 3,000 of these BTTs in effect. And they took off for very understandable reasons.

Part of the promise of globalization is (was?) that capital will go to the places where it is most needed – we’ll see money move from richer countries with few(er) clear investment opportunities to places in need of capital to get their growth off the ground.

Ok so now you’re Apple and you’ve decided to start producing iPhones in India and, critically, selling them there. You’ve sold thousands of the products and have made millions. Who is entitled to the taxes? Corporates would be in a position where both India and the United States, Apple’s home government, to both tax them. They’ll be double taxed.

You probably don’t feel much pity but that would be a substantial financial hit. That potential hit will likely lead to Apple avoiding investing abroad, so we need to set up BTTs where states decide how much a company like Apple should pay to each government that could make a claim on its profits.

BTTs are long and boring with a whole bunch of niche specifics. The main thing to keep in mind is that firms can basically decide – through allocating their intellectual property to different subsidiaries – where they de jure made their profits even if they de facto got the money somewhere else. So you report your profits in Ireland if you’re a tech company because a lower tax rate will apply to those profits than if they are “booked” in the US.

Money made in the US from US consumers is legally routed in such a way as to show up as money made in Ireland.

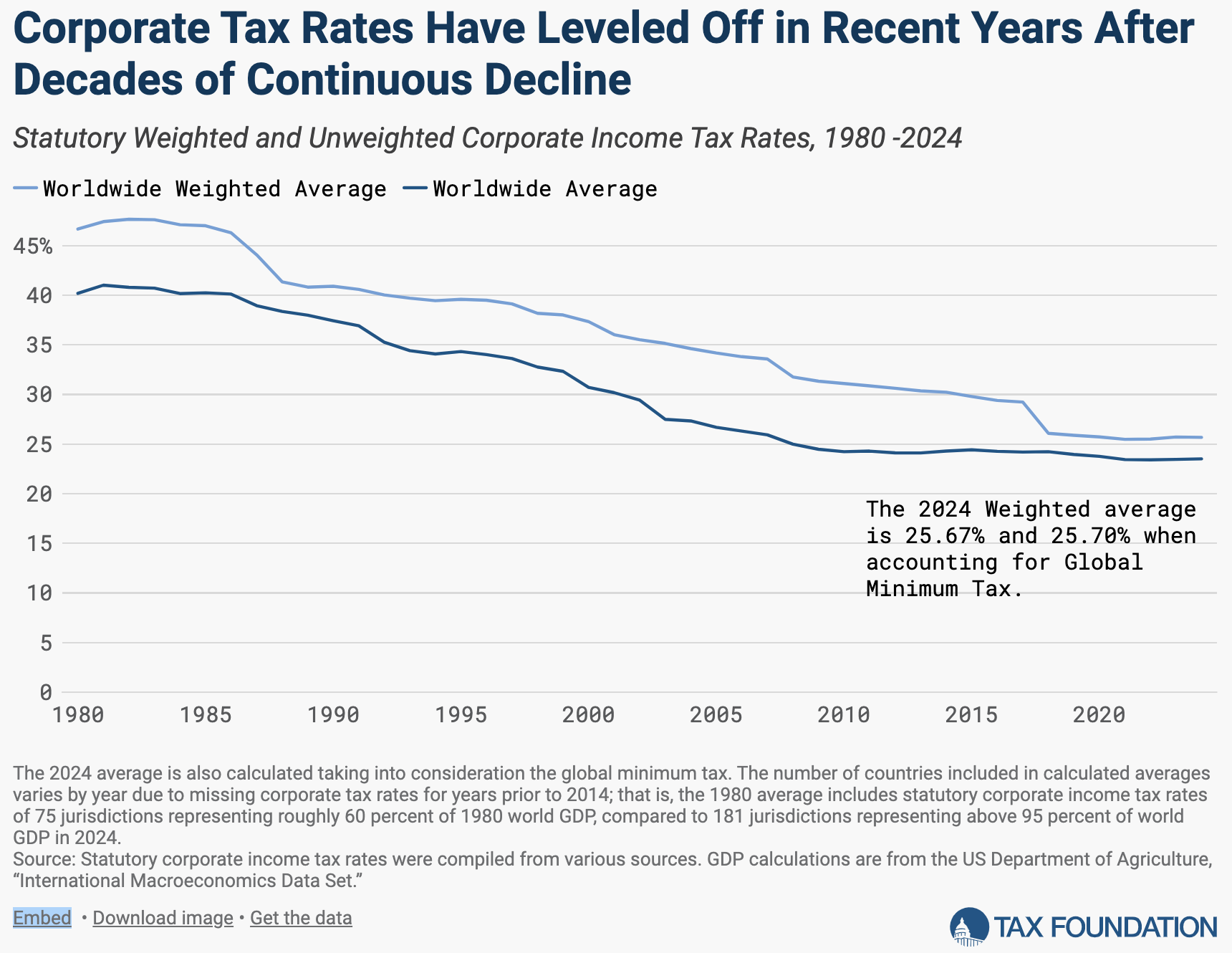

This is the standard narrative and fear around corporate taxation and the way globalization erodes the control of the state over its capital base. Companies can run around and choose the best rates, leading countries to compete and lower their standards. While this hasn’t really played out in most areas, it is certainly true in the tax regime. Corporate taxes have globally been on the decline as countries don’t just compete with their peers. America isn’t just competing with the European Union. India isn’t just competing with Brazil. They’re all in the same networked competition against the likes of BVI and Cayman. This race has been most effectively documented by Arel-Bundock (2017).

These effects are real. Wier and Zucman (2022) estimate that nearly 10% of global taxes were lost to "profit shifting" done by multinational corporation. For the UK and Germany that number was above 25%. lost every year to such “shell” company games.” And they have a broad menu of options. It’s this menu idea that is critical to understanding the offshore world/the political value of tax havens. As Katharina Pistor has argued, the meaning and consequences of money, of capital, depend on its legal attributes. Historically, those rules were decided nationally - like taxes or how a company was governed. But by setting up a company in a place like Panama and making it the owner of your assets in India, it allows you to pick the laws between the Panama and India that make most sense for you individually. Sense usually means economic profits, but not always.

Protecting yourself through the web

The other economic logics are ones that I would expect most readers here to ironically be able to get behind. Consider yourself as a foreign investor in a country with weak rule of law or one of the path to authoritarianism. You’re going to be worried about the government coming and taking over the factory that you built. There are several potential remedies at your disposal but one method you might use to protect yourself is to set up a shell company abroad that “route” your investment into the place you want to build your factory through the shell company. Then when the government comes knocking – they want to seize all your assets – all they can get is the stuff that is on the ground.

Critically, a company or individual could set up a structure that separates the shell company from the corporate as a whole. So let’s say we are talking about a British company that has invested in America. The American government decides it is going to bankrupt the British company and slap it with a bunch of fines. The reach of those fines could be limited to only the offshore subsidiary/shell company and leave the rest of the larger global firm unaffected.

This process is crucial for any investor in a country where the rules of the game are up for grabs. They are particularly crucial in situations where you are dealing with one set of rules or norms in your home country and another in your host. This rationale is seen as key to the global development of “Special Purpose Vehicles” according to Kimberly Hoang in her incredible ethnography on the use of shell companies across emerging market Asia. It’s not about minimizing your taxes. It’s about minimizing your legal liabilities when you are constantly playing between different national rule systems (or playing ‘in the grey” between licit and illicit as she calls it.)

Raising Money Through the Web

Let’s go back to the main reason we have these bilateral tax treaties between countries – the idea was that we want capital to go where it can most efficiently be deployed once we decided we were going to let money flow all around the world (countries liberalizing their capital accounts through the ‘90s). But governments still have lots of national level levers to impact the flow of money in and out of their economies.

They can restrict foreign ownership in certain critically defined sectors, as we’re seeing the US increasingly do, or limit the amount of money that can be sent out by nationals every year even while allowing capital to come in from abroad as India and China do. These restrictions on nationals often create limited space for growth for domestic companies particularly when it comes to financing new investments and that’s where offshore again becomes a lucrative method out of a domestic bind.

By the mid-2010s, companies from emerging markets were using places like the British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands to issue debt even more than their developed market peers because it helps them attract investors who might not be able to invest directly in their home markets (this was largely driven by Brazil and China). Here’s how it works:

- Instead of issuing the bond directly from their home country, the company sets up a related company (called an “affiliate” or “controlled entity”) in tax haven, like the Cayman Islands or Luxembourg. The offshore affiliate officially issues the bond. It sells the bond to global investors, collects the money, and then passes the funds back to the main company in China or Brazil. So investors buy the bond from the offshore entity, not from the parent company in the emerging market, getting around any national level restrictions.

In short, it’s like borrowing money through a middleman based in a neutral, investor-friendly country to make the process smoother and more attractive for international investors.

Many large investors either aren’t allowed or don’t have the tools to invest in emerging market bonds locally. Even when they can, buying bonds through a tax haven is easier because the rules and systems there are more uniform, reducing the hassle of dealing with different tax and legal systems.

Bonds issued in offshore jurisdictions are also popular for tax reasons. Some countries charge extra taxes (withholding tax) on income from countries with low tax rates. Since many investment funds are already based offshore for tax reasons, using them helps avoid some of these tax issues.

These logics are nicely explored by Andrea Binder who argues that the relationship between domestic finance and the state often dictates how much companies from a country will seek to use these offshore financial services. The more the government can financially repress, the more there is a need to go abroad. Repression isn't possible when the state needs the support of the banking sector - in those situations domestic elites often get a lot of the gains of a tax haven through local alternatives.

This impacts the equity side as well, because again at the national level there are often restrictions on how much foreigners can own of company. At the time of writing US investors have the ability to directly invest in over 200 Chinese companies using the American stock market. That’s despite the fact that China has major restrictions on foreign ownership of sectors like tech and education – the exact industries that were booming through the 2010s that foreign investors wanted a slice of. So many Chinese companies use something called a Variable Interest Entity (VIE) structure. They set up a shell company in a place like the Cayman Islands or the BVI. This offshore shell company lists on the U.S. stock exchange and sells shares to American investors.

The offshore company then signs legal contracts with the real Chinese company (the one doing the actual business in China).

These contracts usually give the offshore company control over the Chinese company’s profits and let it pretend to “own” the Chinese business — but not in a legal, direct way. It just has access to the profits. U.S. investors buy shares in the offshore company, not the actual Chinese company. So, they don’t technically own the Chinese business — they just have a claim on its profits through contracts.

The clearest academic explanation of this trend comes from Jason Sharman who wrote about the topic just before the boom in Chinese listings on US stock exchanges.

Why would China allow this? Because there is so much money out there that could help the biggest companies grow, and they wanted some of that growth. But through this method they can basically ban it going forward in a way that would be far less cumbersome with way less economic fallout for domestic actors were they to just let foreign investors steamroll into their not very developed domestic stock market.

Wins for the domestic oligarchy

If you’ve made it this far, I hope it’s clear that there is a constant interplay between domestic institutions and the international taxation regime that helps corporates find new ways to make money. But everything we’ve discussed so far has really been about transnational links – subnational actors operating across borders. But can you still benefit from the international taxation regime even if most of your business is domestically focused? This is globalization. Of course, you can.

Let’s say a wealthy Indian businessman wants to build a factory in India. He could simply use his local bank accounts to fund the construction. Or, he could take a different route: move his money to Mauritius, a country with a favorable tax treaty with India, and then invest that money back into India through a shell company.

Even though it’s the same money coming home, it now counts as foreign investment — giving the investor access to lower taxes, lighter regulations, and possibly more favorable treatment by government agencies. This strategy is known as “roundtripping.”

It's the reason why Cyprus always shows up as one of the top investors in Russia - the island nation has a particularly pro-capital bilateral tax treaty with the Kremlin. Roundtripping became so widespread in India that for many years, Mauritius was the top source of foreign investment into the country — ahead of much larger economies like the U.S. or the U.K. But much of that “foreign” money was actually Indian money disguised as international capital.

Leaks like the Panama Papers exposed how Indian business leaders were using this strategy, and after years of debate, the Indian government revised its treaty with Mauritius in 2016 to close some of the loopholes.

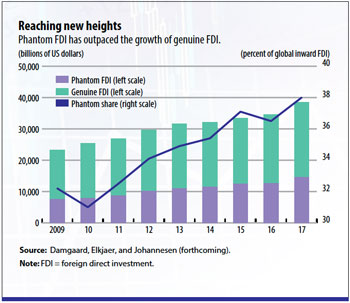

By changing the legal path money takes, wealthy individuals can boost profits and reduce taxes, even when the investment stays entirely within their home country. Roundtripping also distorts how we measure the global economy. What looks like international investment might just be domestic money wearing a foreign mask, making it hard to know where capital is really coming from—or going.

As seen in the figure, researchers from the International Monetary Fund estimate that as much as 40% of the data we think is FDI is in reality roundtripped (phantom in their words) investments.

In sum, tax avoidance by multinational corporation might be the primary reason we should worry about tax havens. But they also five foreign firms a way to protect their assets when making risky investments and can be a critical method to raising money for genuinely valuable economic growth. The downsides are, however, not restricted to tax losses from foreign investments – through roundtripping, wealthy nationals that form the fiscal base of a state can slip through the legal cracks just as effectively.

In the next post in this series, I focus on how all these economic strategies have political wins as well.