The (In)Stability of Growth Models

Rather than treating economic outcomes as purely the result of abstract market forces or static institutions, the Growth Model perspective emphasizes how countries generate and maintain aggregate demand — whether through exports, consumption, or investment — and how this process is shaped by political coalitions, institutional arrangements, and international constraints.

At its core, a GM is defined by:

- The main driver of demand (e.g., net exports, household consumption, foreign direct investment),

- The distributional institutions that support this demand (such as wage bargaining systems, credit markets, and fiscal policy), and

- The international position of the country in global supply and financial chains.

Growth models vary widely—from Germany’s export-led strategy anchored in wage suppression and real undervaluation, to China’s investment-driven model, to Southern Europe’s pre-crisis consumption-led models fueled by credit expansion.

My previous post outlined the core features of these different models. One recurring theme is that they each generate substantial economic and with that political problems. So it begs the question, what sustains growth models in the face of mounting challenges?

Growth Coalitions

At the heart of every growth model lies a political coalition capable of sustaining it. Growth isn’t just about what economies do — export, consume, invest — but about who benefits, who governs, and who consents. This is the insight that Baccaro, Blyth, and Pontusson (2022) bring to the forefront: the stability of a growth model depends not just on economic fundamentals but on the alignment of powerful interests and the ability to build electoral support around them.

They call this alignment a growth coalition. It's the bloc of corporate elites, government officials (elected and unelected), and organized interest groups whose policy agendas are broadly congruent. These coalitions don’t emerge from thin air. They form around specific sectors—such as finance, manufacturing, or real estate—that benefit most from the prevailing growth model.

Crucially, these actors tend to enjoy privileged access to policymakers, shaping decisions behind the scenes as much as through formal institutions.

But growth coalitions face a double challenge:

- Maintaining internal coherence, especially when constituent interests diverge.

- Winning or neutralizing public consent—through electoral alliances, narratives, and policy tools that package elite priorities in socially acceptable terms.

As Baccaro et al. argue, growth coalitions must be "sold" to voters, even if macroeconomic policy is not strictly determined by the ballot box. Here, ideas and discourse play a key role. For example, in Germany, narratives of competitiveness and fiscal discipline help legitimize wage suppression and current account surpluses, even though the majority of workers don’t benefit directly. In Australia, by contrast, large deficits are framed as a sign of investment appeal, which shifts public perceptions about what constitutes economic success

Focusing on growth coalitions helps us understand why repeated attempts at changing a growth model end up failing. As Sierra (2022) shows in the case of Latin America, commodity-driven growth models empower rural elites, concentrate wealth, and often produce real exchange rate appreciation. That combination undermine industrial development and urban wage growth. Attempts to "switch" to more balanced models face resistance not just from global markets but from entrenched domestic interests. She illustrates these points with detailed studies of Argentina and Brazil that follow the same fundamental pattern:

| Dimension | Commodity‑Driven Growth Model | Switching Dilemma |

|---|---|---|

| Macroeconomic Policy | Generates currency appreciation | Allow the currency to appreciate (or promote devaluation) and hurt (or protect) urban and rural tradables |

| Fiscal & Regulatory Policy | Generates economic actors that hold fixed assets and concentrate income | Create an investment-friendly climate or redistribute resources to the urban sector (taxation, price controls, land reform) |

| Balance of Power | Generates structural and instrumental power of agricultural elites | Accept the veto power of the rural sector or increase the power of the urban sector |

Similarly, in Turkey and Egypt, growth model shifts—from credit-fueled consumption to export-led or investment-heavy strategies—reflect deeper reconfigurations of power blocs. In these cases, the relevant coalitions are not broad social blocs but narrower alignments of state elites and dominant capital fractions (what Güngen & Akçay term "power blocs").

These insights show that growth models are rarely technocratic. They are political projects advanced by specific actors with distinct interests. The ability of these coalitions to stabilize growth depends on how well they manage both internal contradictions and external pressures (e.g., capital mobility, currency volatility).

Standard Maintenance Mechanisms

Confronting the Climate Crisis

Climate change is often framed as a technical challenge, a matter of pricing carbon or nudging investment. But from the perspective of growth models, the climate crisis is also a political and macroeconomic problem—one shaped by the deep structure of national economies and the coalitions that support them. In this view, a country’s ability to decarbonize depends not just on public concern or technological availability, but on how its economy grows—and who benefits from that growth.

At the core of this insight is a simple observation: the drivers of economic demand shape the politics of climate action. As Nahm (2022) shows, export-led growth models, particularly those rooted in manufacturing sectors like in China and Germany, are paradoxically better equipped to deliver ambitious decarbonization. These are precisely the economies one might expect to resist climate policy due to their carbon-intensive industrial base. Yet, because their growth is driven by competitive, tradable sectors, they have both the industrial capabilities to develop green technologies and the incentives to pursue global leadership in their production.

In these countries, green industrial policies can deliver not just emissions reductions but also new sources of growth, building broad economic coalitions in support of the transition. Established firms can retool for green exports; new entrants can leverage existing supply chains and institutional support. Decarbonization, in other words, becomes a growth strategy, not just an environmental imperative.

By contrast, consumption-led growth models face a steeper climb. With less exposure to international markets and more fragmented industrial bases, these economies struggle to mobilize equivalent green growth coalitions. They may face less opposition from legacy sectors, but they also lack the material benefits—new jobs, export revenues, investment opportunities—that help sell climate policy to skeptical publics and powerful interests. In these contexts, decarbonization risks appearing as a cost, not a catalyst.

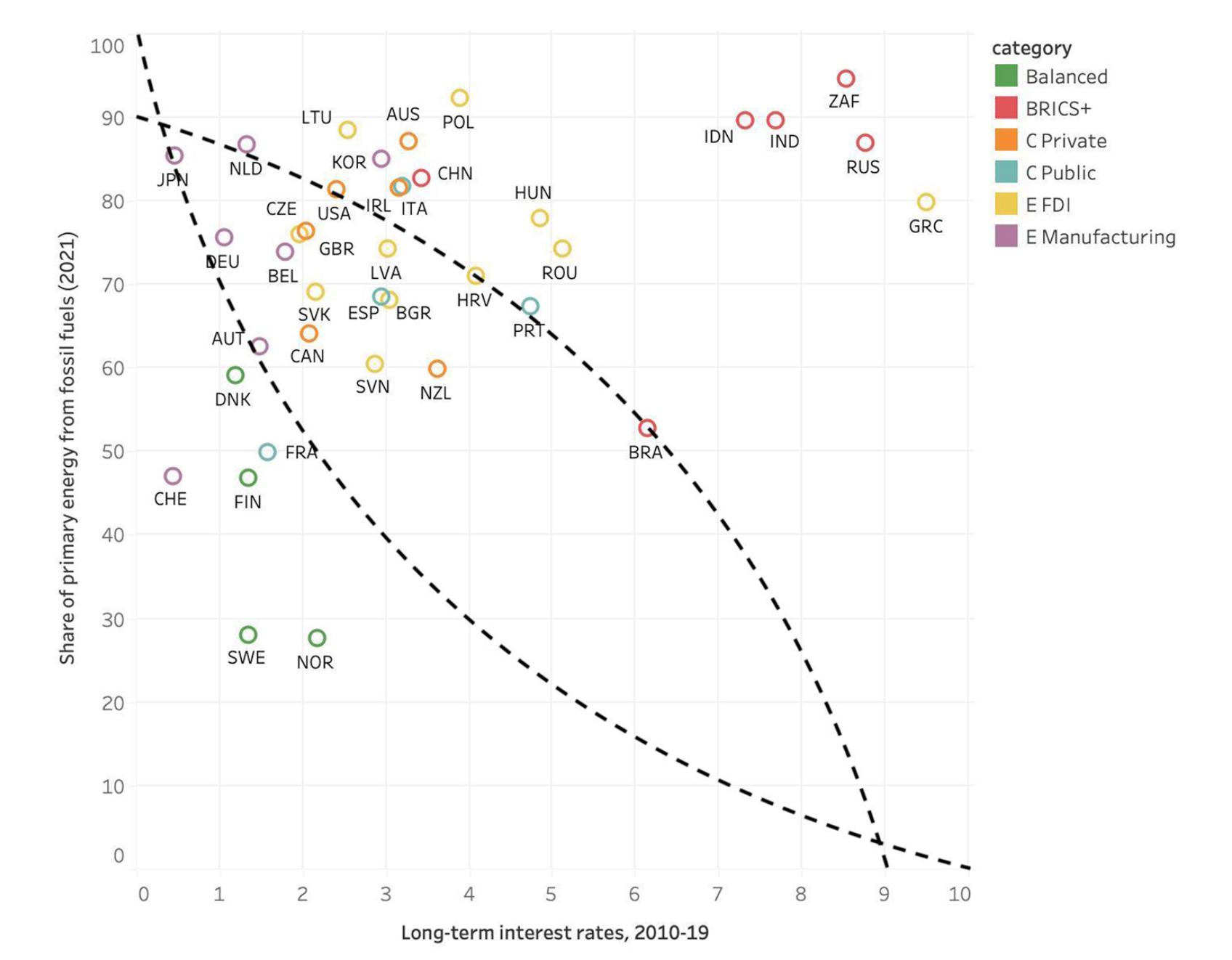

Nahm’s findings echo across other comparative work. Driscoll and Blyth (2025) argue that decarbonization capacity is not just a function of political will but of structural constraints embedded in growth models themselves. They introduce the idea of a “decarbonization possibility frontier”: the intersection between a country’s carbon dependency and its cost of capital. Simply put, the more fossil fuel–intensive an economy is, and the more expensive it is for that state to borrow, the harder it becomes to finance a green transition.

Their analysis identifies a “sweet spot” on this frontier—occupied by countries like France and the Nordics—that combines low fossil fuel reliance with cheap public financing. These countries tend to have balanced or services-export-led models, strong welfare states, and relatively autonomous state institutions capable of planning long-term industrial policy. They are best positioned to pursue what Driscoll and Blyth describe as the three possible pathways to decarbonization:

Nudging finance through emissions pricing or risk-weighted regulations.

Attracting investment via derisking tools and public co-financing.

Disciplining capital directly through mandates, bans, and public investment.

Most countries, however, are not in the sweet spot. For example, FDI-led models—common across the global South and Eastern Europe—tend to be highly carbon-intensive and depend on external capital. Their growth strategies limit policy autonomy, leaving little room for proactive green industrial strategies. Privately financed, consumption-led models, such as the US and UK, may have better financial systems but are often constrained by high debt levels, weak fiscal capacities, and low public investment.

The challenge, then, is not just switching from fossil fuels to renewables—but switching from carbon-based to green-compatible growth models. This requires not only technological substitution but also new coalitions, new investment channels, and often, new political priorities.

Figure: The Decarbonization Possibility Frontier

The implications are profound. Climate transitions that ignore macroeconomic structure may stall, not because of public opinion or technical limits, but because the underlying growth model cannot support them. Conversely, green industrial strategies that align with existing sources of demand and production may accelerate faster than expected—not in spite of capitalism, but by redirecting it.

As both Nahm and Driscoll & Blyth emphasize, not all states can decarbonize the same way. Some can attract private capital. Others must lead with public finance. Some will succeed by building green export sectors; others must work through redistribution and consumption. But in every case, understanding the growth model is essential to understanding the possibilities—and limits—of climate policy.