The Political Value of Tax Havens

Why do the world’s elites stash wealth in tropical tax havens and obscure shell companies? The usual answer is taxes. But, like I started the previous post on offshore finance, that explanation ignores a lot of the most interesting patterns we see in the data. Why do elites from places with low tax rates still go abroad? Why do they often send their money offshore in waves rather than constantly?

To get at these answers we need to think of havens as sites of legal arbitrage — the ability to pick and choose legal systems to maximize protections and minimize accountability. This isn’t just about lowering your tax bill. It’s about choosing your own regulator, your own legal jurisdiction, even your own definition of ownership.

Setting up a company in BVI, or these days Nevada, doesn't just give you a new menu of tax rules, but rather a massive body of commercial law to protect your property. It's not simply secrecy. It's the rule of law.

This post walks through three political uses of offshore finance: shielding wealth to avoid a political crisis, acquiring international legal protections through strategic routing, and boomeranging capital back home as "foreign" money to protect it from one’s own government.

Secrecy Before the Storm

The 2004 Orange Revolution upended domestic politics in Ukraine and we are still very much dealing with its global ramifications. The Kremlin aligned Kuchma-Yanukovych led group of elites was foisted out of power, replace by a new wave of "orange" oligarchs backing Viktor Yushchenko. John Earle and his co-authors (2021) use the political shock to assess how political connections change property protection strategies.

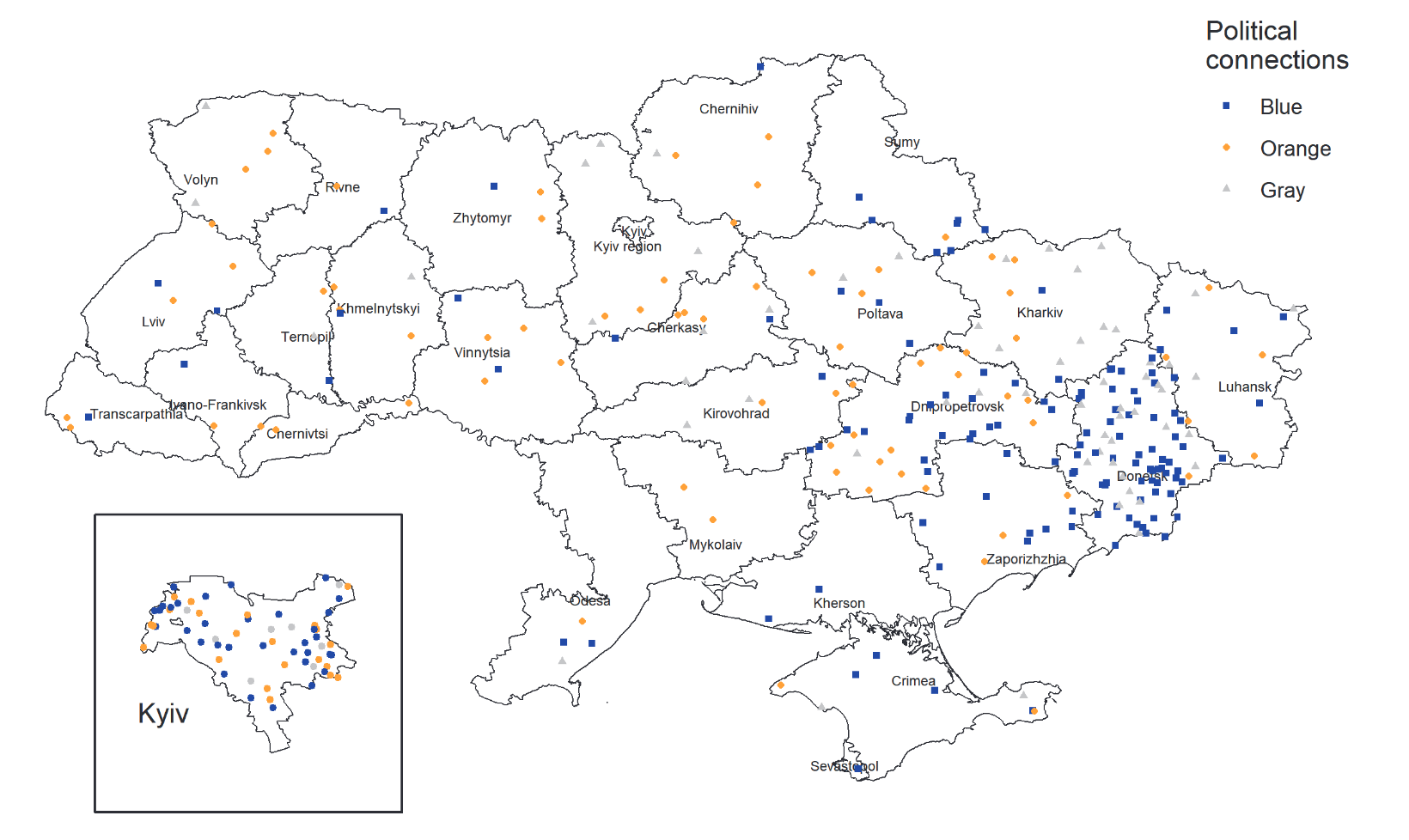

They managed to construct the ownership chains of 300 of the biggest companies in the country. The figure below shows how distinctly the earlier elites, the "blue" oligarchs, operated from the new orange faction. Largely separate geographies and mostly dealing within their own cliques. Note that only one firm shows up as "grey" - owned by oligarchs from both the different factions. That degree of political-to-economic) separation is something we see repeated across contexts and affirmed via recent experimental work.

The authors then combine the fine-grained firm-level data with information from the Panama Paper to illustrate what they refer to as "defensive ownership."

Oligarchs aligned with the outgoing regime took a series of steps to hide their wealth: inserting foreign or offshore firms into ownership chains, distancing themselves from direct control, and shifting legal responsibility to proxies or related parties. These legal methods help elites shelter assets from a potentially hostile new government.

Crucially, these changes were not random. They were politically patterned, with firms linked to the losing faction, the blue oligarchs, far more likely to restructure ownership in legally protective ways. The new orange oligarchs were also more likely to employ these legal methods before they "came to power" via the revolution.

This is not just a post-crisis reaction, but it is systematic. Focusing on the 2007–2012 period due to data constraints, Bayer et al. make another powerful use of the Panama Papers. They combined the incorporation data with global news reports on expropriation and property confiscations from the massive GDELT dataset and show that when headlines about asset seizures spike in a country, incorporations of offshore entities by that country’s agents rise shortly thereafter.

This pattern holds even in well-governed democracies, suggesting that the fear of state overreach is enough to push money abroad. It's often a preemptive move to protect against potential threats. A form of political insurance where the underwriters are offshore service providers and the payout is anonymity.

Put simply, it's harder to expropriate someone when you don't know what they own let alone where the money is hidden.

Offshore activity doesn’t just track domestic politics. Sometimes it follows potential international engagement. Specifically, from the International Monetary Fund. The global safety-net/bailout organization, which I describe to my undergrads as the global economy's morning after pill, comes under perpetual scrutiny from academics. They've foisted austerity onto populations that don't deserve it while wreaking the prospects for growth. It is often described as neoliberalism's grabbing hand, which, judging by recent work, allows elites to grab even more.

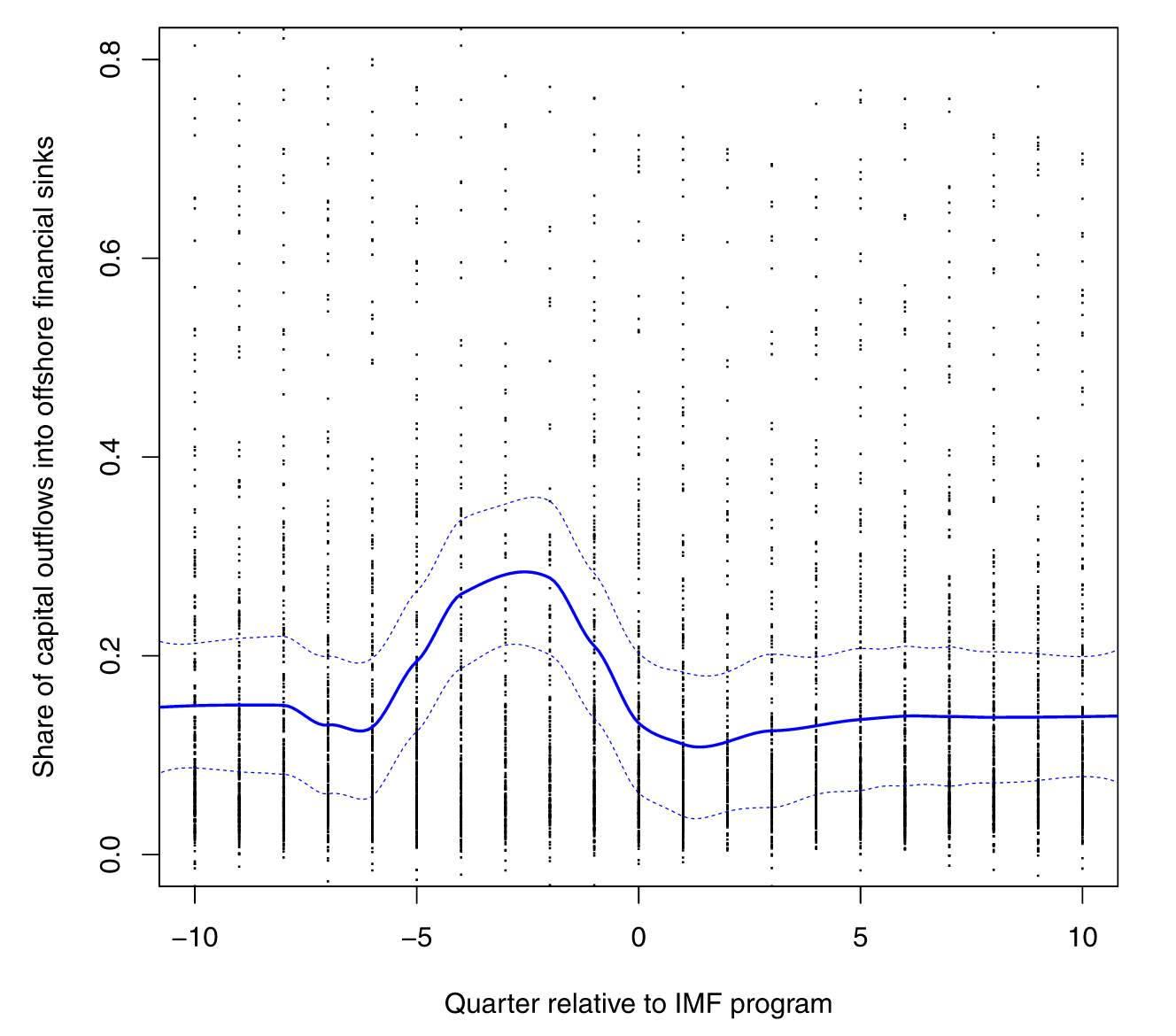

Andreas Kern and his colleagues (2023) argue that elites don’t just run from risk. They manufacture it. In what they call a "crash for cash" strategy, politically connected elites in developing countries draw on IMF assistance not to stabilize their economies, but to extract rents, pile on debt, and then move their profits offshore. Access to IMF bailouts provides a backstop. As long as the country remains plugged into global capital markets, elites can profit in the short term, shift their money abroad, and leave the public with the bill.

Using macro-level data on IMF programs, capital flows, and offshore wealth (derived from Bank of International Settlements data), the authors show that the presence of offshore bank accounts correlates strongly with a government’s willingness to tap IMF programs—particularly when governance is weak and elites are politically entrenched. The story is in the image below.

This is not occasional opportunism; it’s a systematic form of political insurance. The IMF was designed as a lender of last resort. But in weak states, it can turn into a financial escape hatch for elites.

Sometimes the international engagement may not be about enriching yourself. It might stem from the international actors you are afraid of. I'm hesitant to write about this fully since it's my own work with Lorenzo Crippa, and it still hasn't been published, but it looks like elites structure their wealth not just with their domestic government in mind. They are just as scared of getting hit by the United States whose propensity for sanctioning individual foreigners is unrivaled.

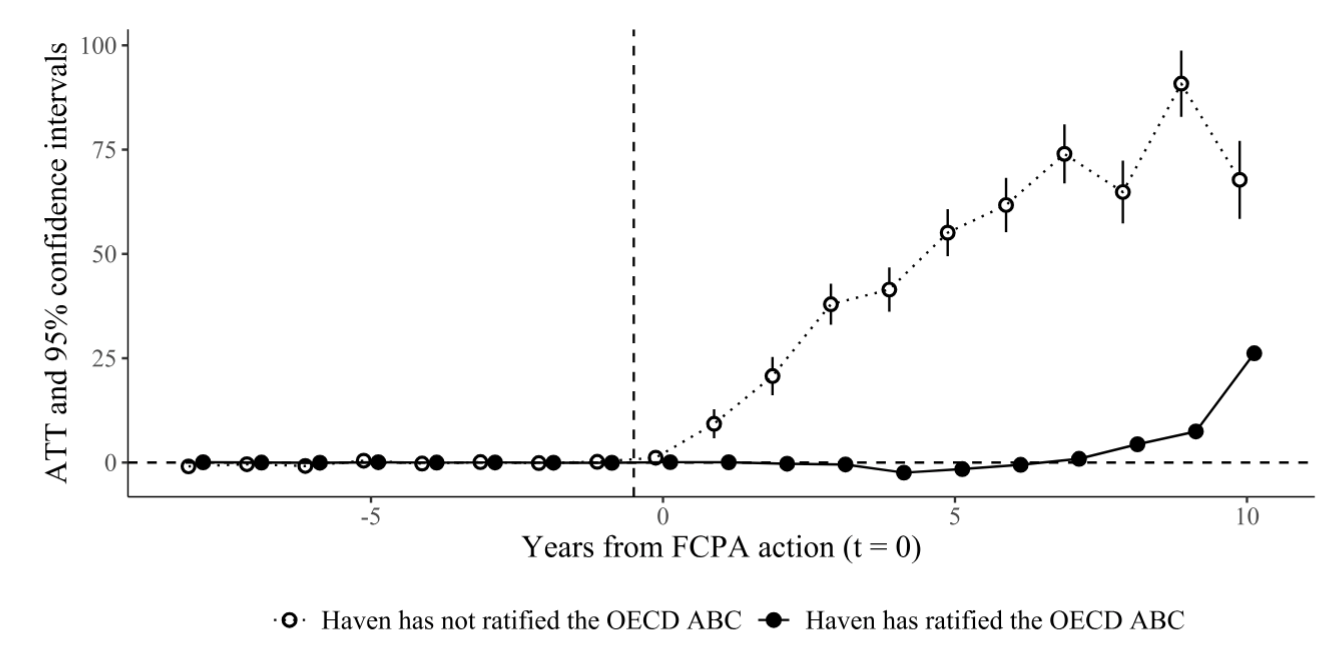

More specifically, the figure below shows what happens when the United States begins to investigate corruption in the elite's country. Following a successful FCPA action by the US - situations where the DoJ charges a foreign corporation operating in the host country - offshore incorporations from that country skyrocket. Even more damning, the money flows to tax havens that have not agreed to cooperate with corruption investigations by the US.

Picking Your Legal Battlefield

The above section is really about the conditions when an elite shops for anonymity, usually relying on the strong domestic privacy laws that virtually any haven has. But recent work indicates that the international laws a haven signs up for have their own dire political consequences. Not all tax havens are created equally, they have different Bilateral Tax Networks that are key to minimizing taxes paid, but they also have different Bilateral Investment Treaties (BIT).

There are now over 3,000 BITs signed between countries in the global economy. They vary in terms of specifics but virtually all of them (95% to be exact) give foreign investors in a country the right to sue their host governments for violating their property rights.

So let's say an American company has a dispute with the South African government. Maybe the South African government decides to nationalize a mine owned by the Americans. The US company could sue South Africa in a neutral international venue for the damages caused.

You can see the logic for why governments might want to sign up for these treaties - if an investor doesn't trust them, doesn't trust the independence of the courts system in a potential investment location - a BIT is supposed to allay those fears. Firms have an outside, credible legal option that should deter governments from messing with their commercial affairs. In theory, the promise of legal security brings much-needed foreign investment in return.

There is lots to say about the regime - I'll write up a full post at some point - but I want to focus here on how tax havens (inadvertently) undermine the gains for governments. Some scholars have argued that Multinational Corporations actively set up shell companies in order to gain access to investment treaties against a host state when their home government doesn't have one.

To keep up the example, if the US and South Africa don't have a BIT, the argument goes that the US firm would have invested in South Africa through a company set up in a tax haven that does in fact have a BIT with South Africa. That still let's them sue.

A recent paper illustrates this is potentially the case using data on the incorporation and investment structures of the 500 largest firms across the global economy. But work by Calvin Thrall shows that this is likely only to be happening under conditions when firms are investing in particularly politically risky countries.

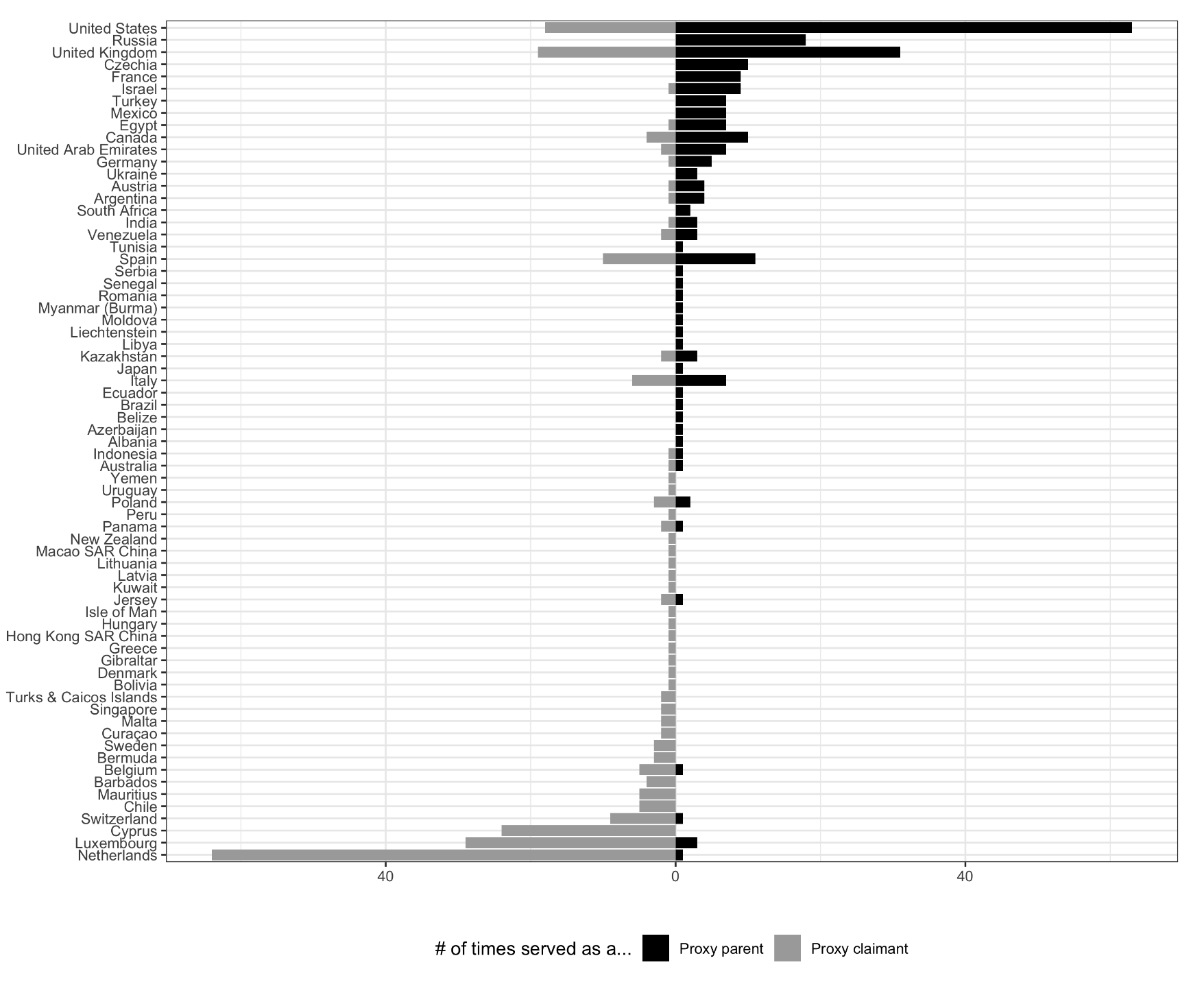

That doesn't mean the shell games don't matter across the board. Not in the least. The data collected by Thrall shows that these instances of treaty shopping - in the investment regime, where an MNC uses one of its affiliates or shell companies to sue a government when it lacks an investment treaty with the host - is responsible for 75% of the damages claimed under the investment regime. $88 billion won. The figure below shows the massive mismatch between who is filing cases versus who actually stands to benefit in these "proxy arbitrations."

Even more interestingly, Thrall uses data on nearly 6500 MNCs and their 57,000 subsidiaries. He compares the optimal route for minimizing taxes versus gaining access to BITs and shows that the vast majority of the work is done by the economic, rather than political/legal, incentives. But again that doesn't mean this doesn't matter.

There's a huge overlap between the investment regime and the taxation regime - from the conduit companies that Thrall identified, 94% of the companies that provided investment treaty access also provide tax relief.

The main point is that whether or not firms and elites are strategically seeking out these investment treaties, they are able and regularly do use the offshore world to file cases against governments. The intent was for these cases to be filed when governments seized property but they are increasingly used to challenge "indirect expropriations." These are situations where new regulations might hinder the firm's future profits. Want to get kids to smoke less by adding graphic health warnings on cigarette patches? You might get sued by an international tobacco company as Phillips Morris famously did to Australia.

Bringing the Legal Battle Home

Using a tax haven to sue a government is basically happening because international law often treats where the money is coming from as the basis for the nationality of an investor. If Cyprus has a great tax treaty with Russia, we see lots of firms from around the world send their money to Cyprus and then to Russia to gain access to the tax treaty. So American money might show up as Cypriot money in Russia leading to a better tax rate.

And that's also what drives the "roundtripping" that I discussed in a previous post - situations where an elite or firm from CountryA sends the money to a tax haven and then right back home to CountryA so that they show up as investors from abroad. De facto locals, de jure foreign.

You can probably guess where this story is going now. Over the past two decades, individuals have learned how this system works and filed cases against their home government through international venues. The most famous example of this is the case by GML/Yukos - one of the holding companies for Mikhail Khodorkovsky and his trusted partners. Khodorkovsky was the richest man in Russia in 2003 before he was imprisoned by the Putin regime. Some of his business partners fled and filed the biggest ever case in the history of the investment regime.

Oligarchs vs. Kleptocrats fighting over the spoils of a former empire. GML, the Khodorkovsky crew, eventually won a $50 billion judgment against the Kremlin. It's gone through many waves (which I recap in my forthcoming book...), and most observers of the foreign investment know all about it. But they tend to write it off.

In my co-authored work with Calvin Thrall we show that it isn't an anomaly. Again this is some of my own, unpublished work so I don't want to dwell on it too much, but the descriptive stats paint a very different picture than what traditional observers expect. These "extraterritorial" cases - de facto home claimant against their home state - constitute 8% of the cases filed in the regime. Yet these cases aren't even supposed to occur.

The regime is were intended to protect foreigners in a signatory country.

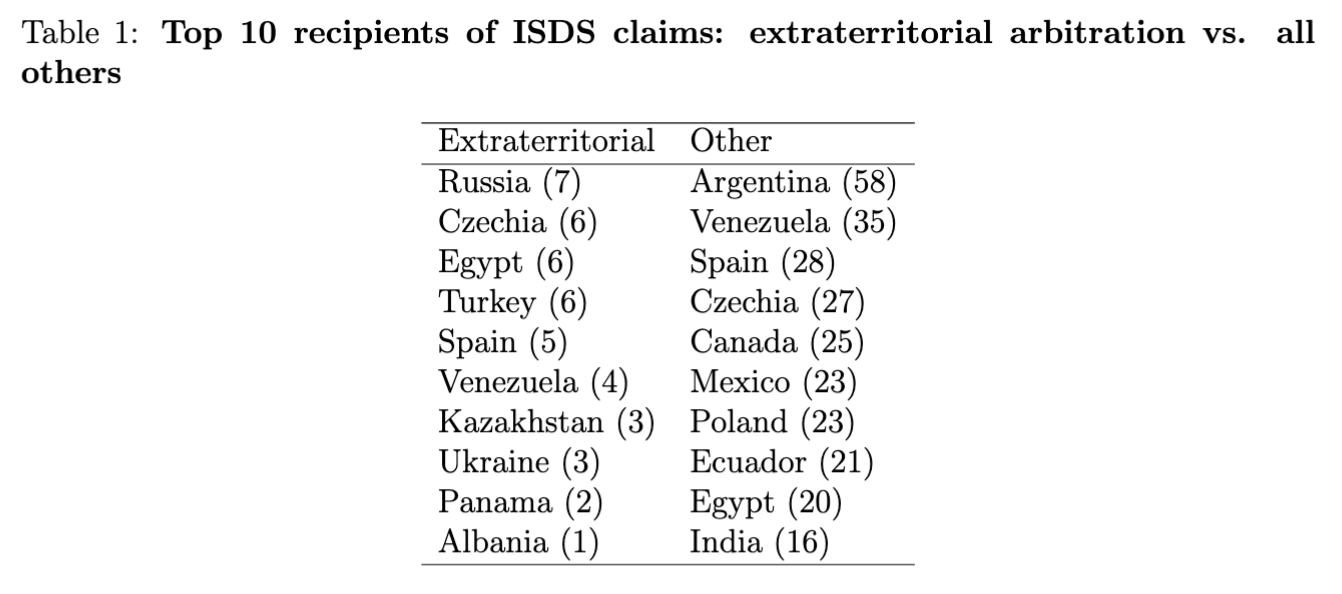

Moreover, that 8% of cases represent just about 41% of the claims under the regime. The table below compares the countries that are on the receiving end of these extraterritorial arbitrations versus standard disputes involving a multinational firm against a host.

The lists are noticeably different - extraterritorial arbitrations tend to involve governments where we've seen major elite battles take place. One exception is Spain where a series of renewable energy laws were challenged, suggesting OECD governments will not be held back from these political maneuvers as they try to take more control over their economies.

Offshore Finance as a Political Technology

Tax havens are not just shady corners of the financial system. They are essential infrastructure for political elites, offering tools to avoid taxes, yes, but also to sidestep regulation, preempt crises, and launder domestic capital into untouchable foreign form.

They enable a form of legal arbitrage, where the powerful pick and choose which laws apply to them. In a global economy where treaties, secrecy jurisdictions, and international courts can be navigated like a map, those with resources can ensure that accountability is always somewhere else.

As Oliver Bullough has argued, the offshore world is a system that allows the world’s wealthiest to float above the nation-state, shielded by paperwork, geography, and legal engineering.

That said, who gets to access these tools is still unevenly distributed and often a function of political machinations. More on that in my next review.