The Politics of Accessing the Offshore Economy

Tax havens can serve multiple purposes. They can allow firms to raise money from foreign investors by skirting domestic laws, and let them bifurcate their business activity to place politically and economically risky bets off their balance sheets.

They serve elites not just by allowing them to reduce their taxes owed, but also by moving their assets out of the reach of expropriation-ready governments and fellow oligarchs, all while letting them shop for the strongest legal protections.

This review, the third in our analysis of tax havens, draws on recent work in political economy and international finance to examine who uses tax havens, how the global offshore system is structured, and just how easy it is to access. The evidence shows that the offshore world is not only highly unequal—it’s also highly organized, and remarkably open to new entrants.

Who Actually Uses Tax Havens?

Recent years have seen a groundswell of important Economics research on the users of tax havens. They often rely on new policy shocks and data leaks to assess which segment of society is managing to hide their wealth most effectively.

At a surface level, the findings aren't shocking: the bulk of the money in places like the BVI or the Caymans belongs to the very richest. The top 0.01%. But that figure distorts how much that varies across countries, and how national incentive structure shape the incentives to hide your money.

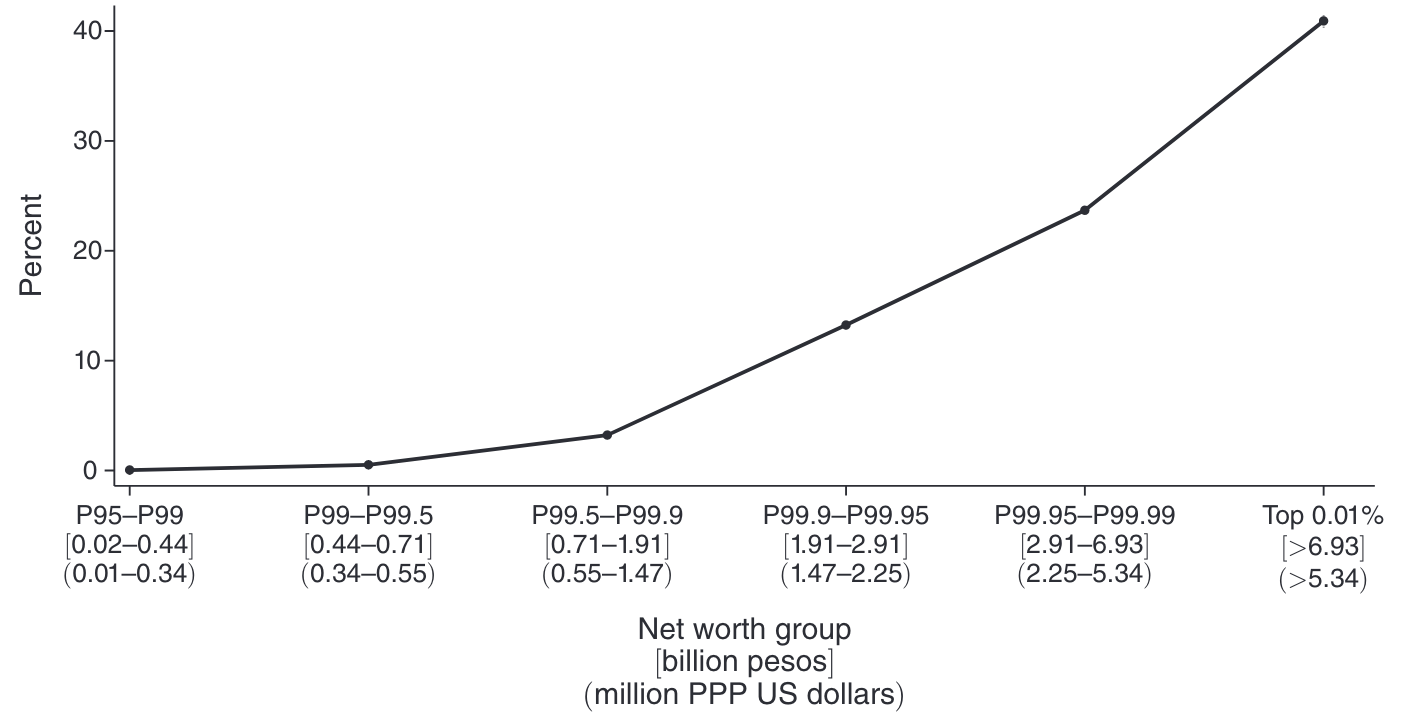

According to work by Londoño-Vélez and Ávila-Mahecha (2021), nearly two-fifths of the wealthiest 0.01% of Colombians admitted to having hidden wealth. 55 times more likely to disclose than those in the top 5%. Among these top-tier evaders, the average individual had hidden one-third of their total wealth, and many only came forward following the international exposure of the Panama Papers.

Colombia’s experience illustrates two key points. First, tax evasion scales with wealth, and second, compliance improves when evasion is credibly threatened, especially by leaks or international scrutiny. Although it accounted for a small fraction of Colombia's super-wealthy, those who were named in the Panama paid twice the amount of taxes after the leak. We might bemoan how the world didn't change after the ICIJ's efforts, but it did have tangible effects in some countries, striking fear in enough rich people in Colombia for the country to track down wealth equivalent to 1.73% of its GDP. And the effects last. In the authors words:

We find that tax compliance is persistent: three years after their revelation, disclosers report 49.2 percent more wealth and, by virtue of disclosing the return of those assets, also pay 39 percent more income taxes—a magnitude similar to what Alstadsæter, Johannesen, and Zucman (2018a) find in Norway.”

The authors used a tax amnesty program - by 2015 some 50 countries had set up programs to get their citizens to declare their missing money with limited punishments - to derive these figures.

Leenders et al. (2023) take a similar approach in The Netherlands, a country often viewed as a rule-abiding tax collector. They study the return details of some 27,000 wealthy dutch citizens and find that offshore tax evasion is heavily concentrated among the “merely rich”, not the ultra-wealthy.

While the top 0.01% (the “super rich”) owned just 7% of amnesty wealth, the P90–P99.9 bracket accounted for 67%. And among these amnesty participants, declared offshore assets made up 30% of their total wealth—a sizable share for those ostensibly below the billionaire class.

One explanation lies in proximity: border effects with Belgium and Germany made cross-border tax evasion more accessible. Another is just simple incentives. The effective tax rate at the top of the Dutch distribution may have been too low to make evasion worthwhile for the truly wealthy. Plus, the Dutch are a key player in the offshore finance network (as seen in the next section) and there are plenty of tools elites can use at home.

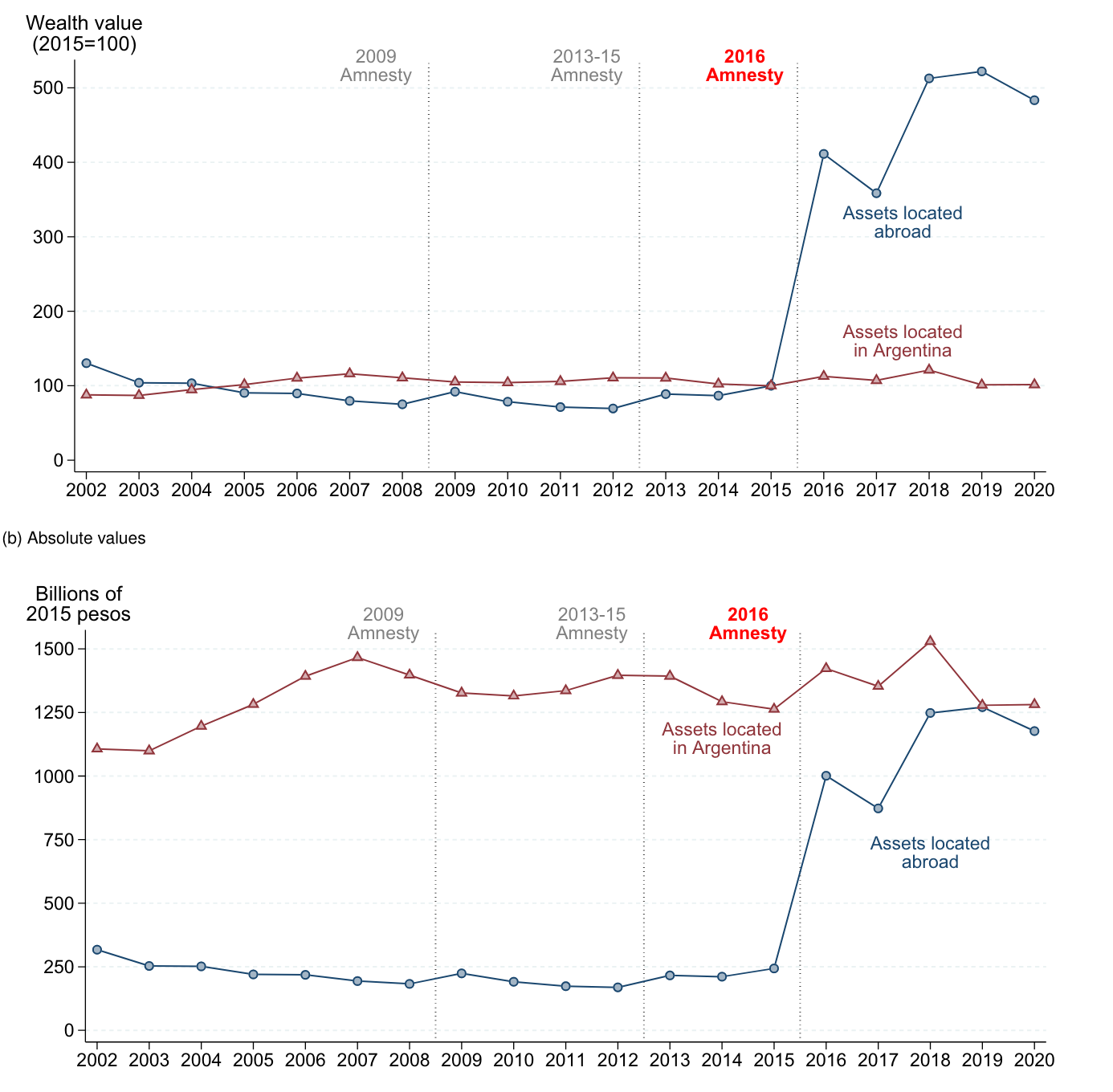

If Colombia and the Netherlands show two sides of the offshore coin, Argentina offers up the bank note. In what is likely the most ambitious amnesty program ever implemented, the Argentine government in 2016 recovered assets equivalent to 21% of GDP, almost all of which had previously been concealed.

Londoño-Vélez and Tortarolo (2022) find that over 80% of the disclosed assets were held abroad, mostly in jurisdictions like Uruguay, Switzerland, and the British Virgin Islands. Notably, a large chunk was also in the U.S.

Again, the wealthiest led the surge in terms of the amounts held abroad. The top 0.1% of earners doubled their declared wealth, and reporting correspondingly increased. Yet most of these assets were not repatriated.

Even when Argentina raised taxes on foreign holdings, wealthy evaders preferred to pay the penalty rather than bring their wealth home. Incredible. The authors posit that the apparent anomaly is less about taxes and more about insulation. Offshore assets are a form of insurance against economic instability: they guard against inflation, capital controls, and unpredictable shifts in monetary policy, as I discuss on the economic value of tax havens.

But we also know from the political science scholarship that this behavior could instead be driven by the need to just keep the assets governed by stricter foreign laws, outside the grabbing hand of a future leftist government. I don't know, say the Kirchners.

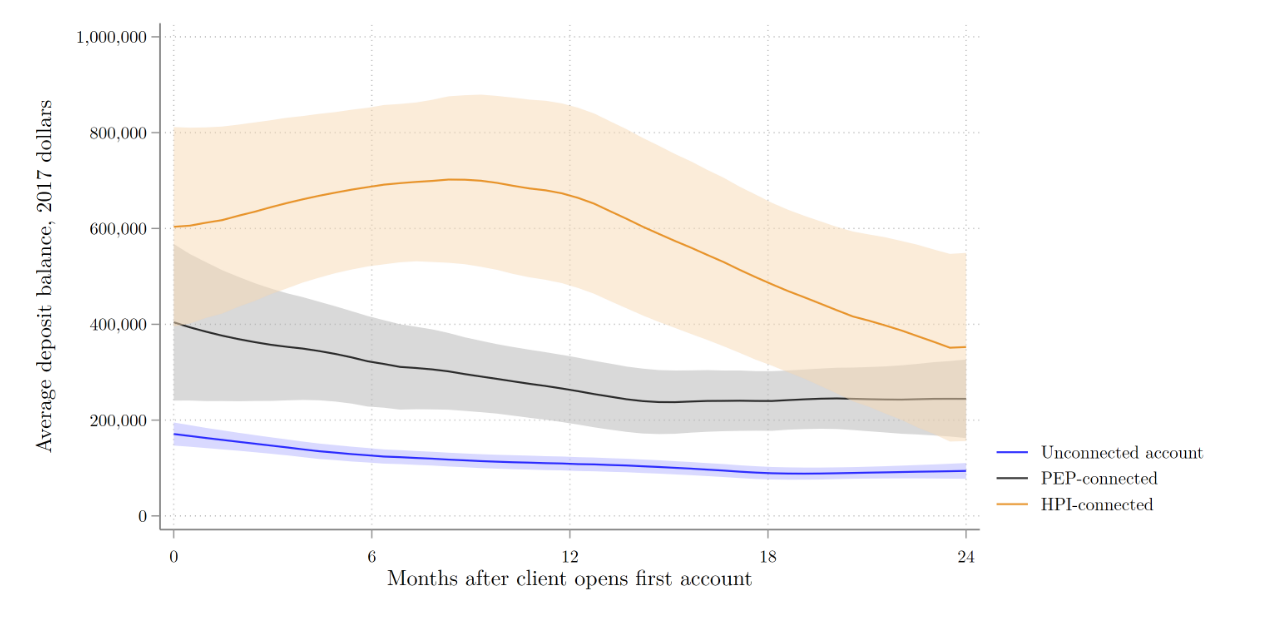

Clearly, offshore wealth is not randomly distributed. It clusters not only by income and geography, but [also by power]. Matthew Collin (2021) provides perhaps the most granular look at this pattern using leaked bank data from the Isle of Man. He finds that politically exposed persons (PEPs)—including politicians, their families, and close associates—are significantly more likely to use tax havens than other clients. These PEPs hold more wealth and perform more transactions than the average user, but still shield less than High Profile Individuals (HPIs) like sports stars.

The overwhelming majority of these assets were registered in classic tax havens, and PEPs were more likely to hold funds in places like the Isle of Man or the British Virgin Islands. The high sophistication of the politically exposed could be from fear of lack of punishment or instead as a means of protection from the state.

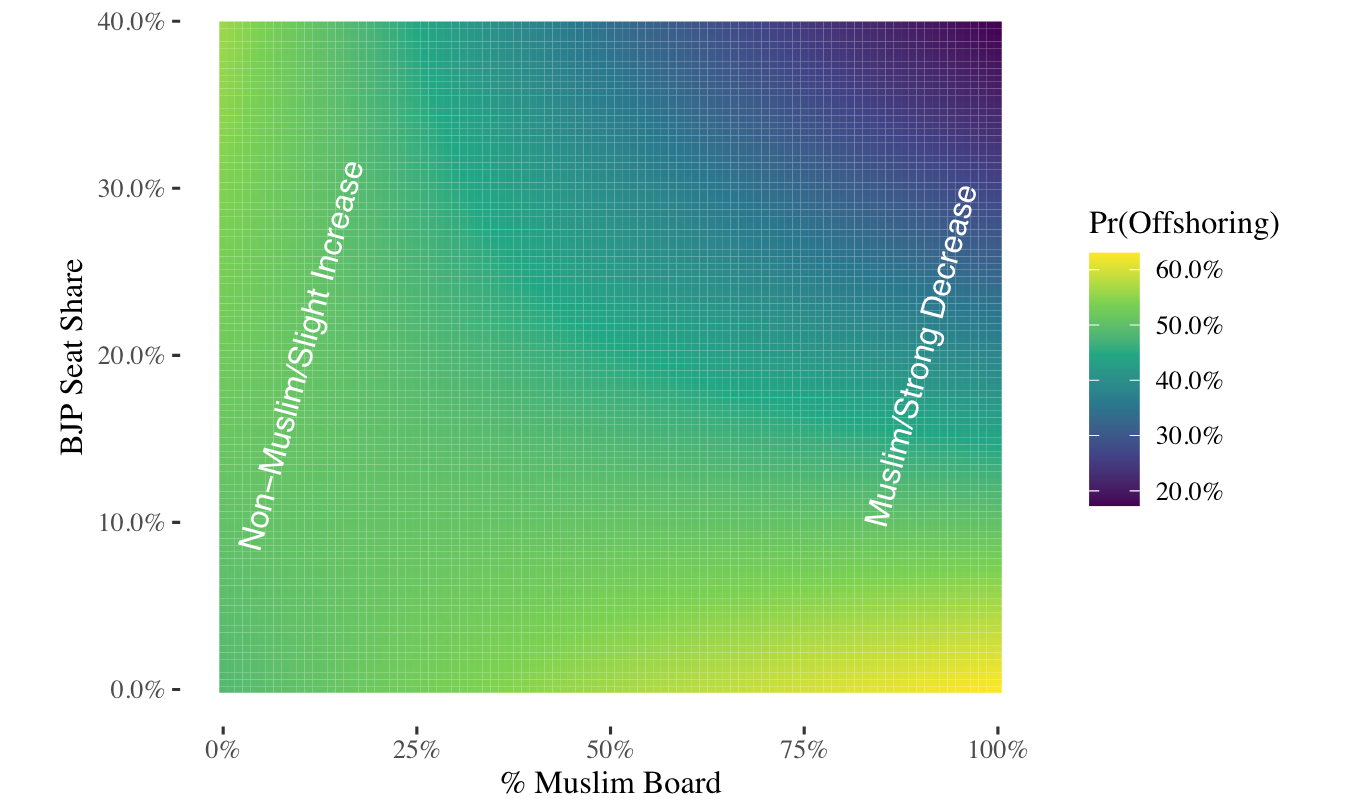

A recent working paper by Kubinec, Morse and Pandya indicates it might be the former. Rather than examining direct political connections, they instead study how religious identity plays into offshoring. Drawing on the ICIJ Offshore Leaks data and Indian firm-level financial statements, they find that when the Hindu-nationalist BJP gained seats in a state legislature, Muslim-led firms were far more likely to exit the offshore space than Hindu-led ones.

For smaller Muslim-owned companies, offshore activity declined by nearly 50% in some cases.

Larger firms with more resources may be able to maintain their offshore presence, but smaller firms lose access to these protective financial tools, compounding inequality.

Sinks, Conduits, and the Curious Case of the UK

At the Price of Power, we've so far mostly looked at the demand-side for offshore. The next two sections move us firmly into the supply-side.

Not all tax havens do the same job. Some are where the money ends up. Others are where it flows through. This basic distinction—between sink and conduit jurisdictions—helps make sense of the architecture of offshore finance.

While conduits rely on transparency and treaty networks, sinks—where the money stays—look quite different. These economies are small but hold disproportionately large amounts of external assets. Their appeal lies in secrecy, negligible taxes, and legal insulation.

By contrast, conduit jurisdictions—such as the Netherlands, Ireland, and the UK—specialize in moving profits through the system. Their role is to facilitate the smooth, tax-light transfer of capital from one country to another, often through a chain of shell entities.

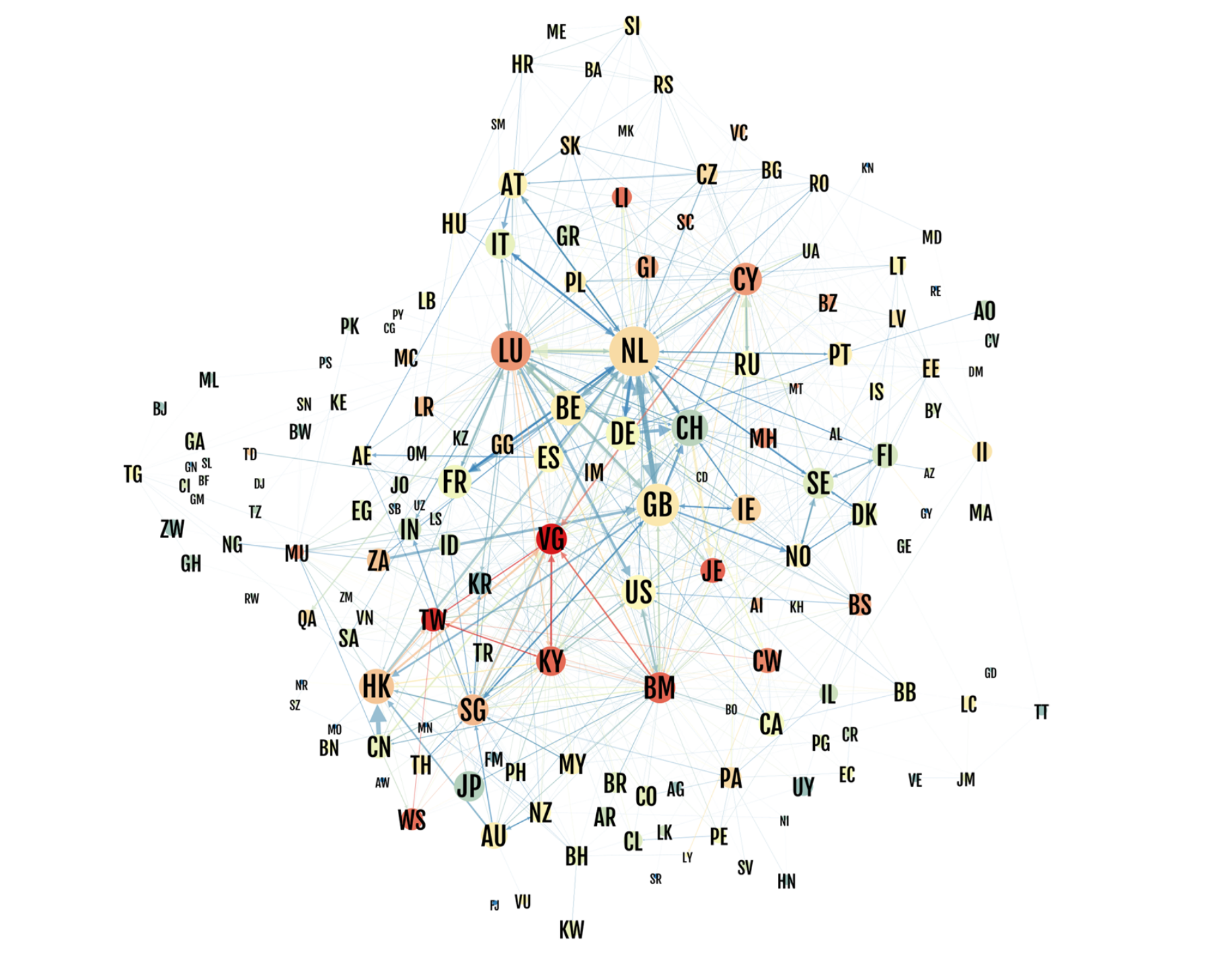

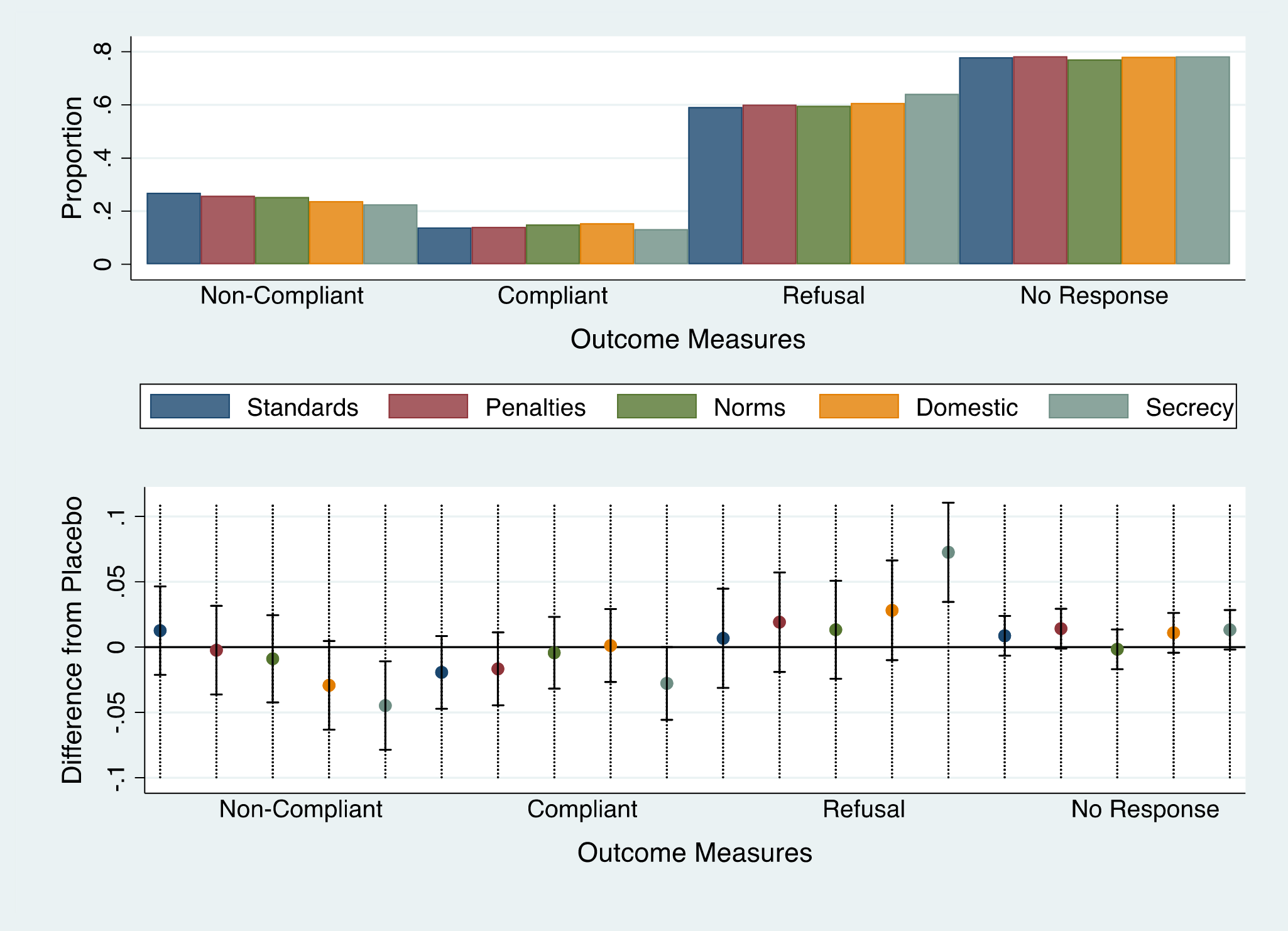

Garcia-Bernardo et al. (2017) analyze over 71 million corporate ownership links to show just how concentrated this system is. Offshore finance isn’t scattered. It's a centralized network. The Netherlands and the UK stand out as the top global conduits, each accounting for capital flows twice the size of the next largest jurisdiction, Luxembourg. These countries are not just pass-through points. They offer legal certainty, tax treaties, and reputation, making them ideal intermediaries for multinational firms. No one blinks twice when they see a Dutch-registered company, but they probably should.

Sink jurisdictions look very different. They hoard capital without much economic activity. And they don’t always fit the stereotype. Taiwan, for example, is a major but underrecognized sink, driven by its tech firms, banking secrecy, and lack of transparency commitments. Its role is often missed in official statistics due to its exclusion from IMF reporting - China won't allow that recognition.

This division of labor matters. Conduits and sinks aren’t interchangeable. Conduits depend on their legal systems and international credibility; sinks rely on opacity. That creates asymmetries in how the system can be regulated. OECD conduits are easier to pressure through policy and treaty reform. Sinks—especially microstates or diplomatically sensitive jurisdictions—are considered harder to reach (but wait till the next section).

The structure also varies by sector. Holding companies dominate conduit chains, while administrative and opaque sectors cluster at the end of sink routes. There are further inevitable geographic patterns. If you are a businessman in East Asia, you'll be looking at Hong Kong and Singapore before thinking about the BVI or the Netherlands.

And that's again why it's worth focusing on the role of the UK. It continues to sit as the bridge point between East and West. Past imperial glory and all.

Nowhere is this clearer than in Butler to the World, Oliver Bullough’s eye-opening portrait of London as the world's elite financial concierge. Britain’s strength lies in its professional enablers: elite-trained solicitors, accountants, estate agents, and PR consultants who help wealthy foreigners move, manage, and launder their wealth with minimal scrutiny. And they all pat each other on the back as they do it.

Bullough shows that there is an undergirding logic whenever the UK considers changing its offshore role. A defeatism. "If we don't do the dirty, someone else will anyway." He further details how British Overseas Territories like the British Virgin Islands and Gibraltar were transformed into offshore powerhouses through coordinated efforts between colonial administrators and Westminster politicians.

Enforcement is patchy at best. Bullough reports on a 2019 review that found 90% of UK financial regulators hadn’t collected the basic information needed to identify high-risk firms, and a quarter weren’t conducting any supervision at all.

How Easy Is It to Use a Tax Haven?

Academics often get a bad rep for sitting back and watching the world go by. Afraid to get their hands dirty. The next couple of projects we'll discuss should blunt those fears. Or at least illustrate that some professors are proficient at using and abusing the offshore world.

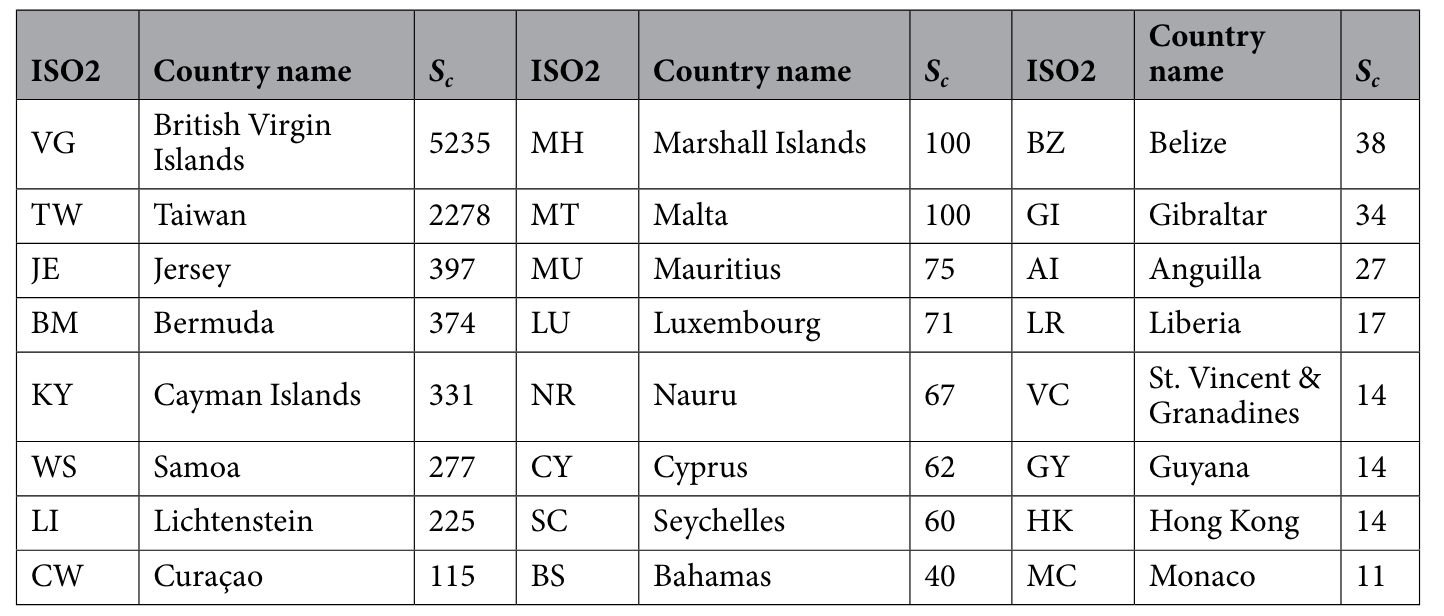

Findley, Nielson, and Sharman (2014) conducted a set of experiments to see how corporate service providers - the people who set up shell companies - assess the risks of their clients and whether they follow international standards. Their team posed as fictitious clients and contacted over 3,700 offshore middle men in 181 countries, asking to open anonymous shell companies.

The results were not encouraging. Nearly half (48%) of replies failed to request proper identification, and 22% didn’t ask for any documents at all. Mentioning the international rules in place did nothing to change their behavior compared to a neutral baseline email. The only slightly encouraging result was that emails that could be construed as coming from terrorist affiliated entities got far less responses.

Contra what many people expect, the companies operating in the most conventional tax havens, which get the most public scorn, had relatively high compliance rates. The United States, on the other hand, was one of the worst offenders. Of 1,722 U.S. providers contacted, only 9 required full certified identity disclosure.

As journalist Casey Michel details in American Kleptocracy, U.S. states like Delaware, Wyoming, and South Dakota have built their business models around financial secrecy. Delaware alone has more registered companies than residents, generating over $1.5 billion annually in incorporation fees. Michel even describes state officials pitching Delaware’s legal structures abroad—touring East Asia to attract elites from Taiwan and China with the promise of anonymous ownership and low-to-no taxes.

South Dakota went further still. It transformed the trust—originally a medieval asset protection tool—into a dynasty trust with no expiration date. These trusts protect wealth permanently, allow secrecy for beneficiaries, and shield assets from inheritance taxes. At the time of his writing (2019), South Dakota trusts held circa $900 billion in assets.

The U.S. isn’t a tax haven by accident. It’s a competitive actor in the global market for anonymity. What Findley et al. uncovered in their field experiment—how easily shell companies can be formed with no real oversight—is a direct result of these political and legal choices.

In a follow-up study, Findley et al. (2025) extended their experiment to banks and financial intermediaries, contacting over 5,000 banks and 7,000 incorporation service providers across more than 200 jurisdictions. This time, they asked not just about company formation, but also about opening corporate bank accounts—and tested whether firms reacted differently to requests that signaled high levels of risk: references to terrorism, corruption, or secrecy.

The authors took great pains to ensure they weren't breaking the law. Lying to a bank can get you into serious trouble, so they used hypothetical numbers based on the consulting services that the authors provide.

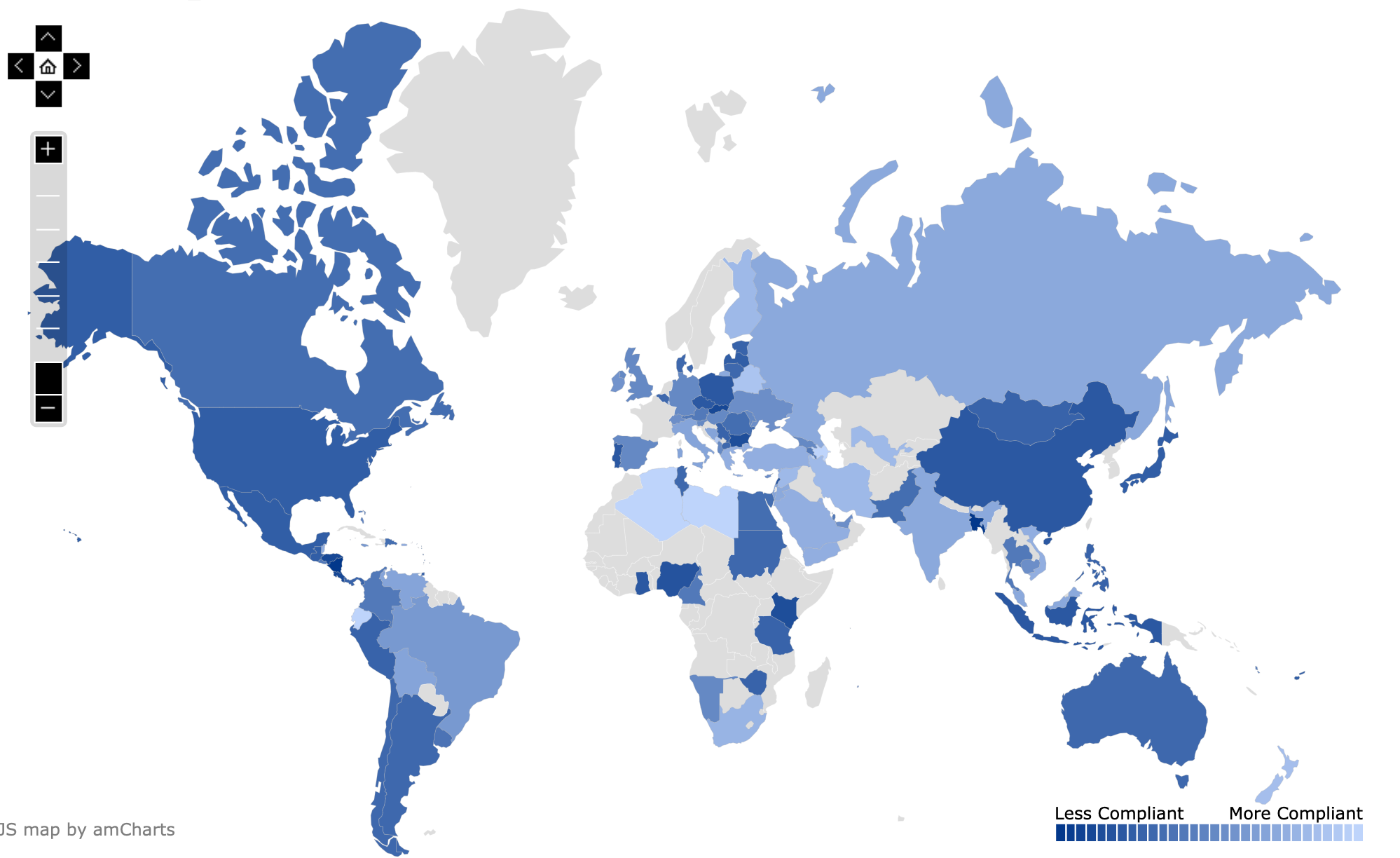

Once again, most firms failed to apply meaningful due diligence. The vast majority simply didn’t respond at all, and among those who did, few adjusted their behavior in response to risk. For example, inquiries sent under a “terrorism” profile—an alias from Saudi Arabia claiming to work for a charitable organization—led to slightly more refusals, but not significantly more scrutiny.

The figure below lays out the full response set for banks per the different treatments. The bottom panel illustrates the difference in response rate compared to a neutral, control email. Almost none of the treatments were different than the control, as seen by the error bars in the bottom panel consistently crossing zero (indicating a null effect).

And once again references to international standards, such as FATF guidelines, failed to produce better results—and in some cases made compliance worse.

You might be tempted to reach for an optimistic take from the top panel - most emails actually went without response so maybe the banks are really complying there. But that non-response rate was no different for treatment vs. control emails. It just says banks are really bad at responding to emails even if they could make money off them.

The authors also do something extremely cheeky. They fielded a survey to political scholars before running the experiment to assess their priors. The bulk of scholars expected less risky countries to increase response, and more responses the higher the sums of money at play. Neither really panned out.

The team theorize that banks and service providers make binary decisions: accept or ignore. They rarely fine-tune their compliance. They are like other organizations, following routinized scripts. Even a job where you might be facilitating money laundering can be rather dull. It's still just a job where people push the papers and tick the boxes they've been taught to before they check out.

The banality of a complex system is often what makes it so powerful.